by Dick Edelstein

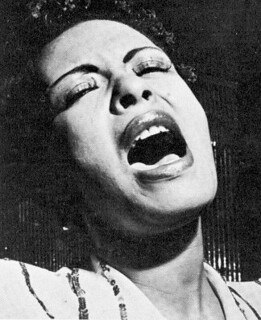

Following Hulu’s release of “The United States vs Billie Holiday”, the singer’s musical career has become a topic of discussion. The docu-drama is based on events in her life after she got out of prison in 1948, having served eight months on a set up drug charge. Now she was again the target of a campaign of harassment by federal agents. Narcotics boss Harry Anslinger was obsessed with stopping her from singing that damn song – Abel Meeropol’s haunting ballad “Strange Fruit”, based on his poem about the lynching of Black Americans in the South. Anslinger feared the song would stir up social unrest, and his agents promised to leave Holiday alone if she would agree to stop performing it in public. And, of course, she refused. In this particular poker game, the top cop had tipped his hand, revealing how much power Holiday must have had to be able to disturb his inner peace.

Following Hulu’s release of “The United States vs Billie Holiday”, the singer’s musical career has become a topic of discussion. The docu-drama is based on events in her life after she got out of prison in 1948, having served eight months on a set up drug charge. Now she was again the target of a campaign of harassment by federal agents. Narcotics boss Harry Anslinger was obsessed with stopping her from singing that damn song – Abel Meeropol’s haunting ballad “Strange Fruit”, based on his poem about the lynching of Black Americans in the South. Anslinger feared the song would stir up social unrest, and his agents promised to leave Holiday alone if she would agree to stop performing it in public. And, of course, she refused. In this particular poker game, the top cop had tipped his hand, revealing how much power Holiday must have had to be able to disturb his inner peace.

Writing in The Nation, jazz musician Ethan Iverson noted that all three films based on Holiday’s life have delighted in tawdry episodes without managing to convey the measure of her musical achievement. Hilton Als, in a review in The New Yorker, was unable to conceal his disdain for the recent biopic, observing “you won’t find much of Billie Holiday in it—and certainly not the superior intelligence of a true artist.” Both writers insist that Holiday’s memory has been short-changed in the media, and it follows that the public cannot be fully aware of her contribution to musical culture. Iverson’s thoughtful piece analyzes her many innovative contributions to musicianship and jazz vocal interpretation, while here I propose to comment on only a couple of these. But first I want to call attention to the ineffable quality of Holiday’s singing, how her delivery of lyrics and free-flowing phrasing of melody tug at the emotions. Those effects defy analysis; you have to hear Billie Holiday’s singing to know the excitement it conveys. Feeling that emotion comes easily, but describing exactly how she generates it is impossible. Read more »

Wendel White. South Lynn Street School, Seymour, Indiana, 2007.

Wendel White. South Lynn Street School, Seymour, Indiana, 2007.

Santiniketan in my childhood used to attract a lot of foreign scholars, artists and students, which was a boon to a young stamp-collector like me. Every day the sorting at the small post office was completed by mid-morning and many of the residents used to come and collect their mail themselves. I, along with a couple of other children, used to wait there for the foreigners to collect their mail. As soon as one was spotted, we used to scream “Stamp! Stamp!”; they obliged us by tearing off the stamps in their envelopes. Soon I had a thick album of foreign stamps. I used to linger wistfully over every stamp and imagined things about those distant foreign lands. (I remember Swiss stamps said only ‘Helvetia’ on them, which I could never find in the only world map I had at home).

Santiniketan in my childhood used to attract a lot of foreign scholars, artists and students, which was a boon to a young stamp-collector like me. Every day the sorting at the small post office was completed by mid-morning and many of the residents used to come and collect their mail themselves. I, along with a couple of other children, used to wait there for the foreigners to collect their mail. As soon as one was spotted, we used to scream “Stamp! Stamp!”; they obliged us by tearing off the stamps in their envelopes. Soon I had a thick album of foreign stamps. I used to linger wistfully over every stamp and imagined things about those distant foreign lands. (I remember Swiss stamps said only ‘Helvetia’ on them, which I could never find in the only world map I had at home).

Billions of people around the world continue to live in great poverty. What is the responsibility of rich countries to address this?

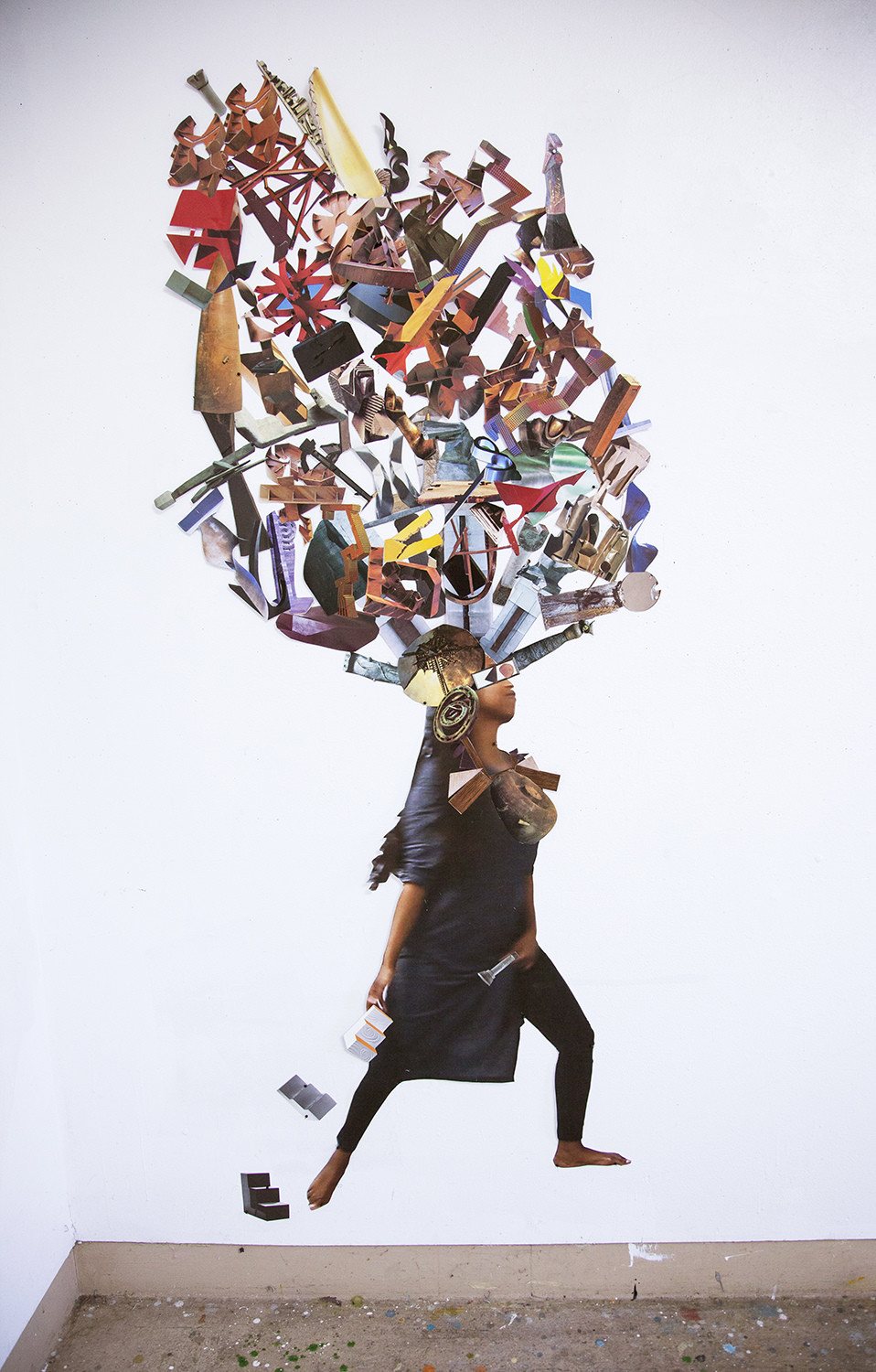

Billions of people around the world continue to live in great poverty. What is the responsibility of rich countries to address this? The best thing about a painting is that no two people ever paint the same one. They could be sitting in the same garden, staring at the same tree in the same light, poking the same brush in the same pigments, but in the end none of that matters. The two hypothetical tree-paintings are going to turn out different, because the two hypothetical painters are different also.

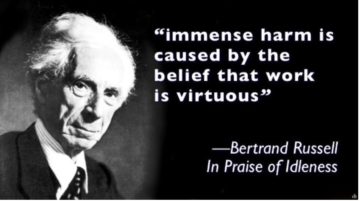

The best thing about a painting is that no two people ever paint the same one. They could be sitting in the same garden, staring at the same tree in the same light, poking the same brush in the same pigments, but in the end none of that matters. The two hypothetical tree-paintings are going to turn out different, because the two hypothetical painters are different also. The work ethic is deeply ingrained in much of modern society, both Eastern and Western, and there are many forces making sure that this remains the case. Parents, teachers, coaches, politicians, employers, and many other shapers of souls or makers of opinion constantly repeat the idea that hard work is the key to success–in any particular endeavour, or in life itself. It would be a brave graduation speaker who seriously urged their young listeners to embrace idleness. (I did once hear Ariana Huffington advise Smith College graduates to “sleep their way to the top,” but she essentially meant that they should avoid burn out by ensuring that they get sufficient rest.)

The work ethic is deeply ingrained in much of modern society, both Eastern and Western, and there are many forces making sure that this remains the case. Parents, teachers, coaches, politicians, employers, and many other shapers of souls or makers of opinion constantly repeat the idea that hard work is the key to success–in any particular endeavour, or in life itself. It would be a brave graduation speaker who seriously urged their young listeners to embrace idleness. (I did once hear Ariana Huffington advise Smith College graduates to “sleep their way to the top,” but she essentially meant that they should avoid burn out by ensuring that they get sufficient rest.)

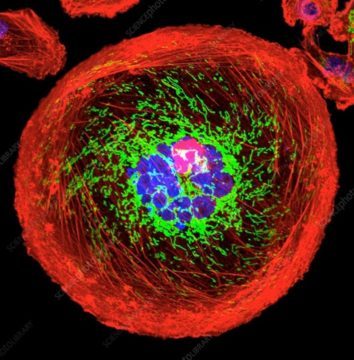

Ninety percent cancers diagnosed at Stage I are cured. Ninety percent diagnosed at Stage IV are not. Early detection saves lives. Unfortunately, more than a third of the patients already have advanced disease at diagnosis. Most die. We can, and must, do better. But why be satisfied with diagnosing Stage I disease that also requires disfiguring and invasive treatments? Why not aim higher and track down the origin of cancer? The First Cell. To do so, cancer must be caught at birth. This remains a challenging problem for researchers.

Ninety percent cancers diagnosed at Stage I are cured. Ninety percent diagnosed at Stage IV are not. Early detection saves lives. Unfortunately, more than a third of the patients already have advanced disease at diagnosis. Most die. We can, and must, do better. But why be satisfied with diagnosing Stage I disease that also requires disfiguring and invasive treatments? Why not aim higher and track down the origin of cancer? The First Cell. To do so, cancer must be caught at birth. This remains a challenging problem for researchers. In the beginning, the god of the

In the beginning, the god of the

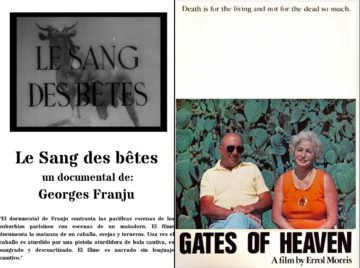

Blood of the Beasts (Le sang des bêtes)

Blood of the Beasts (Le sang des bêtes)