by Thomas Larson

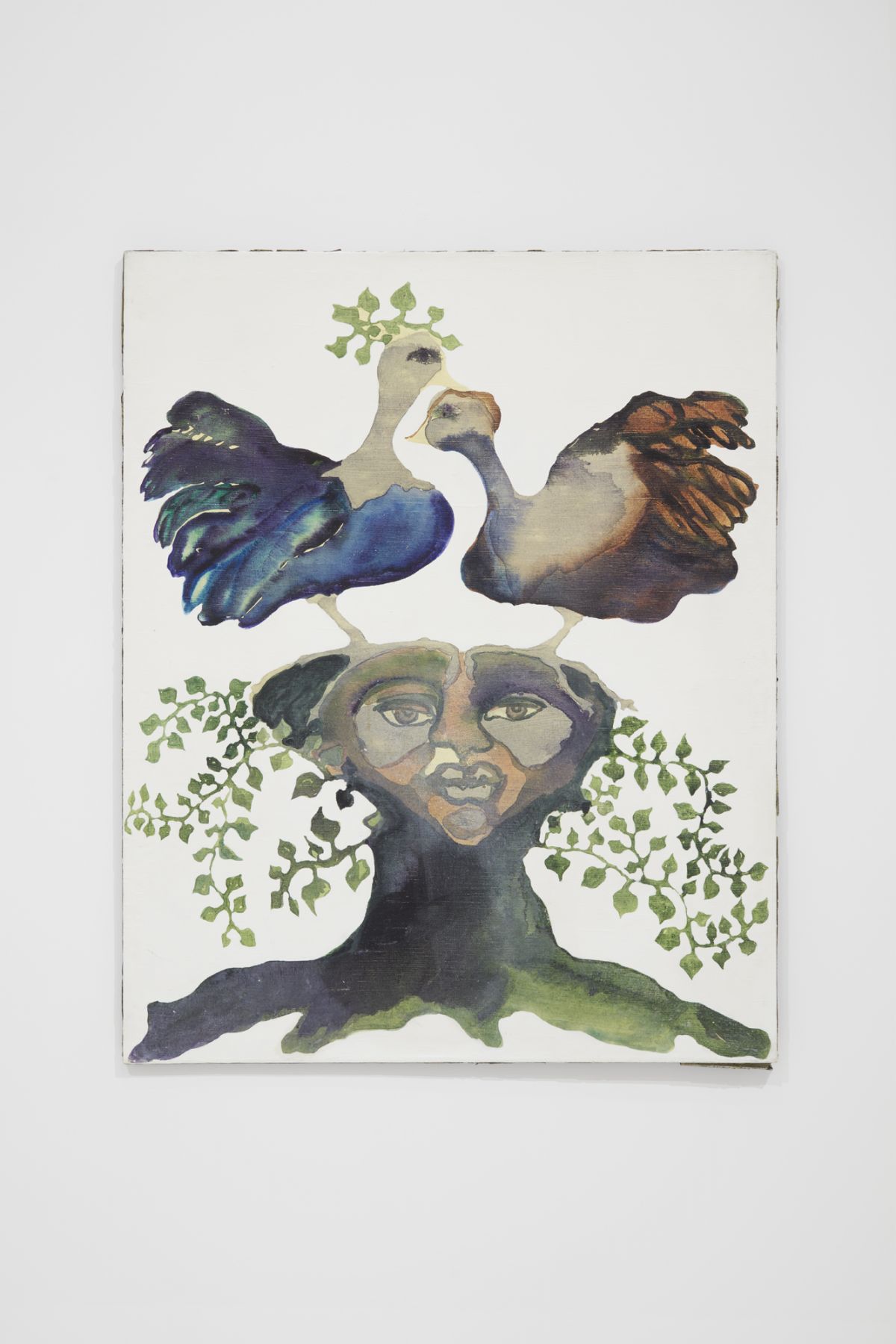

In 1994, Chauvet cave was discovered near the township of Vallon-Pont-d’Arc in southern France. The cave is a spectacular venue for the earliest known rock art made by our ancestors and in no way “primitive.” Deep inside the limestone cavern are hundreds of highly animated wall paintings of bison, bear, ibex, lion, rhinoceros, hyena, wooly mammoth, and horse, “signed” by the red-ochre handprints of the artists. The darkly etched charcoal drawings were sketched in the cave’s smoothed chambers, their walls rounded and pocked from water’s eonic hollowing. In the space are also pudding-like towers of calcium drips, whose conical shapes record the geologic heaping of age. The images, now protected as a World Heritage Site, were done between thirty-thousand and thirty-three thousand years ago.

In 1994, Chauvet cave was discovered near the township of Vallon-Pont-d’Arc in southern France. The cave is a spectacular venue for the earliest known rock art made by our ancestors and in no way “primitive.” Deep inside the limestone cavern are hundreds of highly animated wall paintings of bison, bear, ibex, lion, rhinoceros, hyena, wooly mammoth, and horse, “signed” by the red-ochre handprints of the artists. The darkly etched charcoal drawings were sketched in the cave’s smoothed chambers, their walls rounded and pocked from water’s eonic hollowing. In the space are also pudding-like towers of calcium drips, whose conical shapes record the geologic heaping of age. The images, now protected as a World Heritage Site, were done between thirty-thousand and thirty-three thousand years ago.

In the first ten minutes of Werner Herzog’s Cave of Forgotten Dreams (2011), the film director and his crew hike up a rock face and squeeze through crawls spaces into the cave. Inside, the artists, paleontologists, and filmmakers don hardhats, test flashlights, and review the rules they must follow. The group’s one-hour descent, guarded viewing, and exit are filmed; afterwards, Herzog edits the footage by using two sound guides: the eerie, improvised evocations of cellist-composer Ernst Reijseger, to accompany the images, and Herzog’s voiceover commentary. Like a choirmaster, his soft, German-inflected, baronial English accompanies us through this sonic and architectural marvel. His voice warms and mystifies the claustrophobic space like a nurse talking us through an MRI. Read more »

One day, I used to say to myself and anyone else who’d listen, I’m going to write a book called ‘everything you know about these people is wrong’. I have given up on the idea, and I expect anyway that someone else has already done it. What prompted the repeated thought was the way in which so little of what well known thinkers and artists did or said is actually reflected in public consciousness,

One day, I used to say to myself and anyone else who’d listen, I’m going to write a book called ‘everything you know about these people is wrong’. I have given up on the idea, and I expect anyway that someone else has already done it. What prompted the repeated thought was the way in which so little of what well known thinkers and artists did or said is actually reflected in public consciousness,

You may know everything that you need to know about the on-going “Critical Race Theory” debate. Indeed, you might have concluded that actually there is no such

You may know everything that you need to know about the on-going “Critical Race Theory” debate. Indeed, you might have concluded that actually there is no such  Where I live in Colorado there are unstable elements of the landscape that sometimes fail. In severe cases, millions of tons of rock, silt, sand, and mud can shift, leading to massive landslides. The signs aren’t always evident because the breakdown in the structural geology often happens quietly underground. The invisible changes can take hundreds or thousands of years, but when a landslide takes place, it is fast and violent. And the new landscape that comes after is unrecognizable.

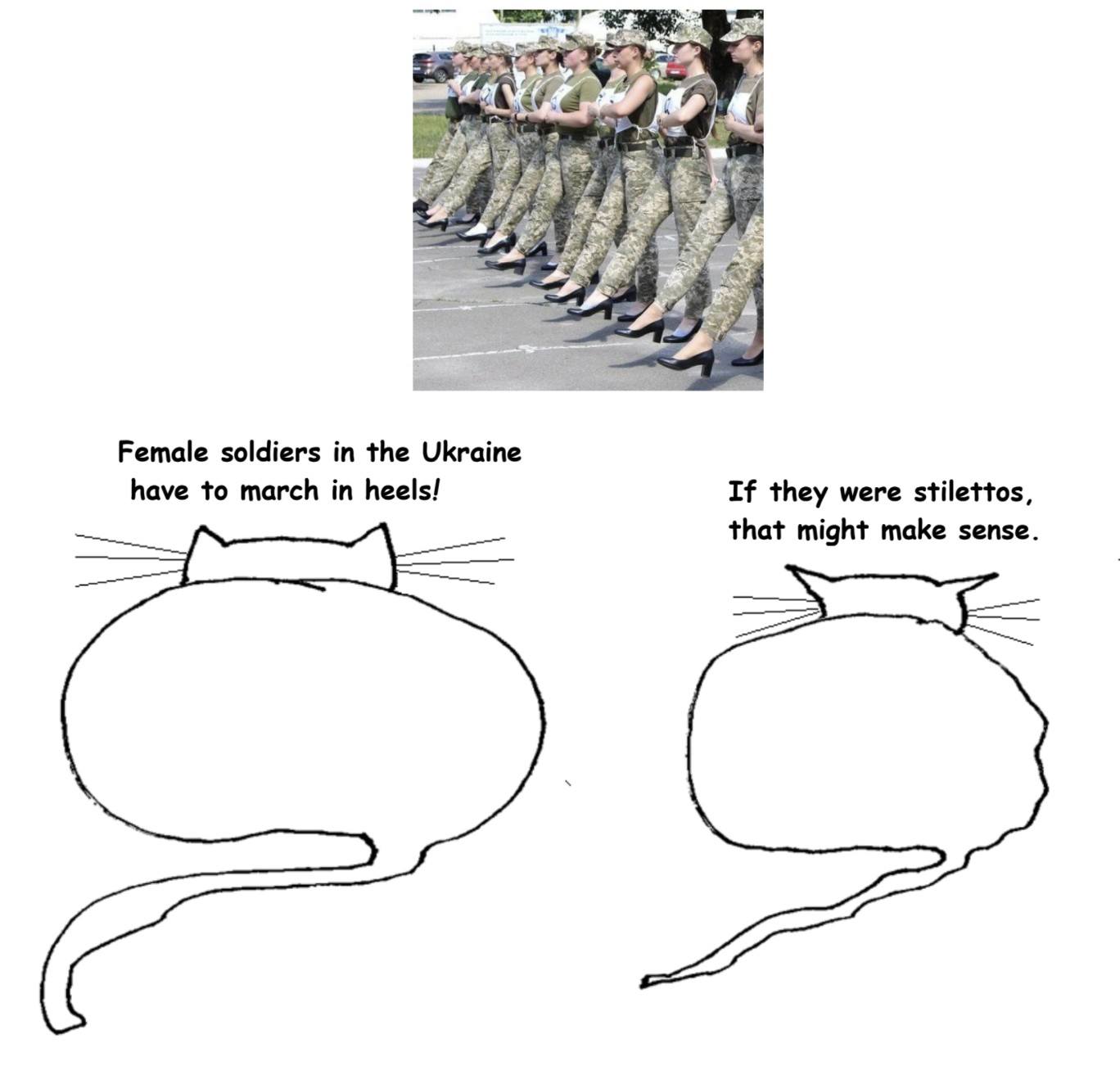

Where I live in Colorado there are unstable elements of the landscape that sometimes fail. In severe cases, millions of tons of rock, silt, sand, and mud can shift, leading to massive landslides. The signs aren’t always evident because the breakdown in the structural geology often happens quietly underground. The invisible changes can take hundreds or thousands of years, but when a landslide takes place, it is fast and violent. And the new landscape that comes after is unrecognizable. A number of issues in the study of nationalism ought to be widely accepted nowadays, most notably perhaps the claim that political nationalism – the idea that a citizen pledges allegiance to a nation-state rather than to a village or a town – is a modern phenomenon. After all, nationalism properly takes hold in a territory when modern tools such as universal schooling are employed to produce a national identity – the inhabitants of a territory must speak the same language and recognise a common culture if a nation is to surface – and this is a product of the last 200 years. A national identity doesn’t come about on its own.

A number of issues in the study of nationalism ought to be widely accepted nowadays, most notably perhaps the claim that political nationalism – the idea that a citizen pledges allegiance to a nation-state rather than to a village or a town – is a modern phenomenon. After all, nationalism properly takes hold in a territory when modern tools such as universal schooling are employed to produce a national identity – the inhabitants of a territory must speak the same language and recognise a common culture if a nation is to surface – and this is a product of the last 200 years. A national identity doesn’t come about on its own.

When I finished my residency in 1980, I chose Medical Oncology as my specialty. I would treat patients with cancer.

When I finished my residency in 1980, I chose Medical Oncology as my specialty. I would treat patients with cancer.