by Joseph Shieber

In a recent essay on Slate, Phil Zuckerman, Professor of Sociology & Secular Studies and Associate Dean of Faculty at Pitzer College and the author of the 2020 book, What It Means To Be Moral: Why Religion is Not Necessary for Living a Moral Life suggests that atheists are more moral than religious believers.

It’s important to be clear about the claim Zuckerman is defending. In particular, in contrast to the stated thesis of his book, Zuckerman is not arguing that religion is not necessary for a moral life. Rather, in his Salon essay, Zuckerman instead suggests that nonbelief is in fact more compatible with morality than religious belief. As Zuckerman puts it, “When it comes to the most pressing moral issues of the day, hard-core secularists exhibit much more empathy, compassion, and care for the well-being of others than the most ardently God-worshipping.”

Zuckerman’s brief for the moral superiority of nonbelievers consists of a list of the positions held more often by nonbelievers than the most dedicated religious believers. In addition to prizing public health during the Covid-19 pandemic, affirming the truth of anthropogenic climate change, and pursuing gun control measures, Zuckerman provides a laundry list of other positions that he suggests highlight the nonbelievers’ greater moral standing:

In terms of who supports helping refugees, affordable health care for all, accurate sex education, death with dignity, gay rights, transgender rights, animal rights; and as to who opposes militarism, the governmental use of torture, the death penalty, corporal punishment, and so on — the correlation remains: The most secular Americans exhibit the most care for the suffering of others, while the most religious exhibit the highest levels of indifference.

My sense is that I actually agree with Zuckerman that the positions that he associates with nonbelievers are the morally right ones. Nevertheless, I am not confident that Zuckerman’s argument establishes what he thinks that it does. Here are three reasons why. Read more »

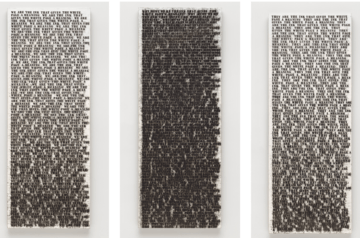

Sughra Raza. Temple Wall Philosophy. Galle, Sri Lanka, 2010.

Sughra Raza. Temple Wall Philosophy. Galle, Sri Lanka, 2010.

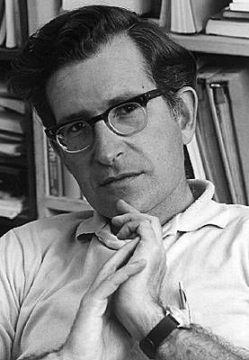

One remarkable redeeming feature of my dingy neighborhood in Kolkata was that within half a mile or so there was my historically distinctive school, and across the street from there was Presidency College, one of the very best undergraduate colleges in India at that time (my school and that College were actually part of the same institution for the first 37 years until 1854), adjacent was an intellectually vibrant coffeehouse, and the whole surrounding area had the largest book district of India—and as I grew up I made full use of all of these.

One remarkable redeeming feature of my dingy neighborhood in Kolkata was that within half a mile or so there was my historically distinctive school, and across the street from there was Presidency College, one of the very best undergraduate colleges in India at that time (my school and that College were actually part of the same institution for the first 37 years until 1854), adjacent was an intellectually vibrant coffeehouse, and the whole surrounding area had the largest book district of India—and as I grew up I made full use of all of these. Unlike her previous exhibit, James chose not to explicitly market

Unlike her previous exhibit, James chose not to explicitly market

The view that everyone who is capable has a basic duty to work and not be idle is the main tenet of what we call the work ethic. Closely related to this are two other ideas:

The view that everyone who is capable has a basic duty to work and not be idle is the main tenet of what we call the work ethic. Closely related to this are two other ideas:

When I was 12 my parents fought, and I stared at the blue lunar map on the wall of my room listening to Paul Simon’s “Slip Slidin’ Away” while their muffled shouts rose up the stairs. As I peered closely at the vast flat paper moon—Ocean Of Storms, Sea of Crises, Bay of Roughness—it swam, through my tears, into what I knew to be my future, one where I alone would be exiled to a cold new planet. But in fact it was just an argument, and my parents still live together—more or less happily—in that same house where I was raised.

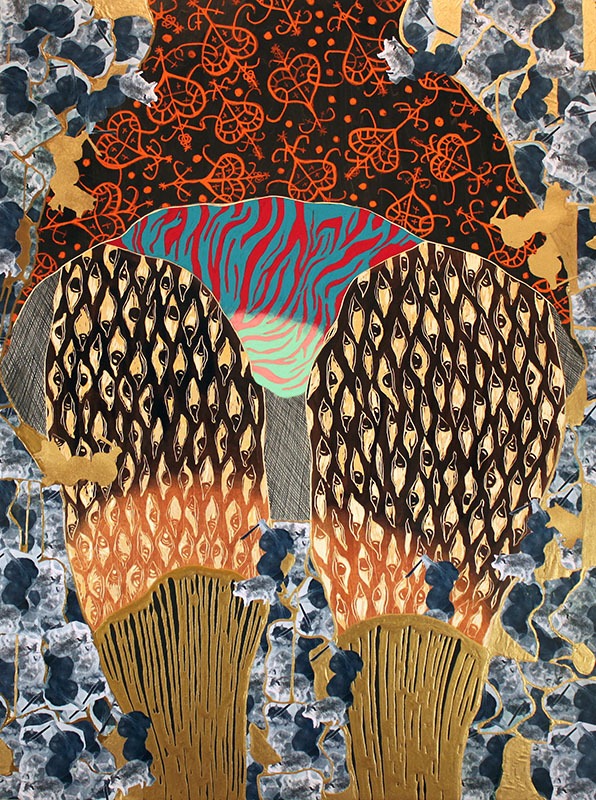

When I was 12 my parents fought, and I stared at the blue lunar map on the wall of my room listening to Paul Simon’s “Slip Slidin’ Away” while their muffled shouts rose up the stairs. As I peered closely at the vast flat paper moon—Ocean Of Storms, Sea of Crises, Bay of Roughness—it swam, through my tears, into what I knew to be my future, one where I alone would be exiled to a cold new planet. But in fact it was just an argument, and my parents still live together—more or less happily—in that same house where I was raised. Didier William. Ezili Toujours Konnen, 2015.

Didier William. Ezili Toujours Konnen, 2015.