by Charlie Huenemann

In discussion with Moritz Schlick and Friedrich Waisman in 1929, Ludwig Wittgenstein said he knew what Heidegger was getting at in his murky assertions about Dasein and Angst. The only problem, Wittgenstein thought, was that humans just cannot speak intelligibly about the highest or deepest things. Not even Heidegger.

“Think, for instance, of the astonishment that anything exists. This astonishment cannot be expressed in the form of a question, and there is also no answer to it. All that we can say can only, a priori, be nonsense. Nevertheless we run up against the boundaries of language. Kierkegaard also saw this running-up and similarly pointed it out (as running up against the paradox). This running up against the boundaries of language is Ethics. I hold it certainly to be very important that one makes an end to all the chatter about ethics – whether there can be knowledge in ethics, whether there are values, whether the Good can be defined, etc. In ethics one always makes the attempt to say something which cannot concern and never concerns the essence of the matter. It is a priori certain: whatever one may give as a definition of the Good – it is always only a misunderstanding to suppose that the expression corresponds to what one actually means (Moore). But the tendency to run up against shows something. The holy Augustine already knew this when he said: ‘What, you scoundrel, you would speak no nonsense? Go ahead and speak nonsense – it doesn’t matter.’”

In this discussion, Wittgenstein was still operating mostly in his Tractatus mode — the one in which he imperiously scolds anyone who fails to assert a meaningful proposition according to the Seven Canonical Assertions carved into his monolithic Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. But we can sense in these remarks that a shift is taking place, as Wittgenstein is no doubt growing up and realizing that the main business of life is filled with nonsense. The meanings of our assertions, as he claimed later in the Philosophical Investigations, are inextricably tangled up with getting things done and living with others. A group of philosophers bound solely to the dictates of the Tractatus would be a sorry, feckless lot — like the logical positivists. Read more »

At age twenty-three, after a brief stint of teaching at Calcutta University, I, accompanied by Kalpana, proceeded to Britain on a Commonwealth Scholarship. The Scholars from different parts of India were asked to assemble in Delhi, from where we were to take the international flight. The only experience I had of an air flight before was when I flew from Kolkata to Guwahati, representing Calcutta University in an inter-University debating competition. That flight experience had not been good, as our propeller-driven Dakota plane had hit a supposed ‘air pocket’. So I had some unnecessary trepidation for the long Delhi-London flight.

At age twenty-three, after a brief stint of teaching at Calcutta University, I, accompanied by Kalpana, proceeded to Britain on a Commonwealth Scholarship. The Scholars from different parts of India were asked to assemble in Delhi, from where we were to take the international flight. The only experience I had of an air flight before was when I flew from Kolkata to Guwahati, representing Calcutta University in an inter-University debating competition. That flight experience had not been good, as our propeller-driven Dakota plane had hit a supposed ‘air pocket’. So I had some unnecessary trepidation for the long Delhi-London flight.

The gender wage gap is a well-documented phenomenon. Many are familiar with the claim that women earn 80 cents on the dollar. A more precise statement would be something like, “In the U.S., according to

The gender wage gap is a well-documented phenomenon. Many are familiar with the claim that women earn 80 cents on the dollar. A more precise statement would be something like, “In the U.S., according to

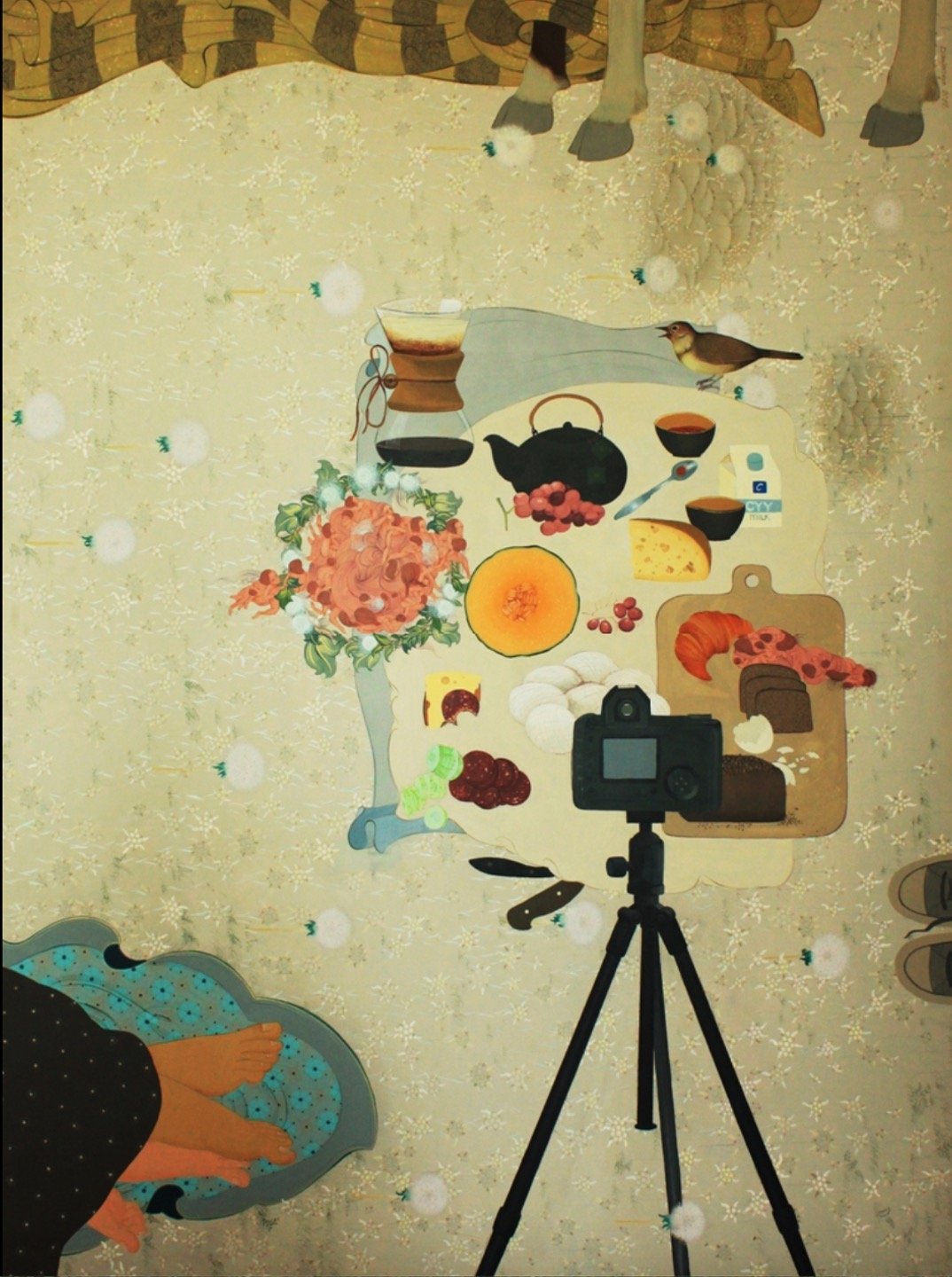

Uuriintuya Dagvasambuu. Aabam Beebem, 2019.

Uuriintuya Dagvasambuu. Aabam Beebem, 2019.

1859 was not a bad year for publishing in Britain. Books that came out that year included Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty, and George Eliot’s Adam Bede. The first installments of Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities and Wilkie Collins’ The Woman in White also made their appearance. And Samuel Smiles published Self-Help.

1859 was not a bad year for publishing in Britain. Books that came out that year included Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty, and George Eliot’s Adam Bede. The first installments of Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities and Wilkie Collins’ The Woman in White also made their appearance. And Samuel Smiles published Self-Help.

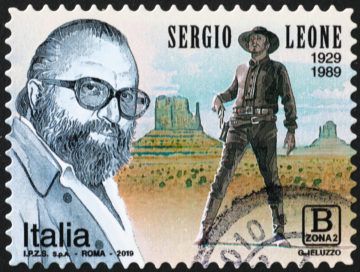

According to the website Rotten Tomatoes, there are four types of movies: good-good movies, good-bad movies, bad-good movies, and bad-bad movies. These types can be identified using the Rotten Tomatoes score for each movie, particularly the relationship between the critics’ score and the audience’s score. Let me explain. Rotten Tomatoes is a website that collects movie reviews and assigns them a rating of either “fresh” (if the review is positive) or “rotten” (if the review is negative). It then calculates the percentage of fresh reviews and assigns this as a score to the movie. If the score is 60% or greater, the film itself is considered fresh, whereas if the score is lower than 60%, the film is rotten. This is a useful way of rating a movie, but there’s a problem here, too. Let’s imagine every reviewer gives a movie three out of four stars, indicating a good film but not a great one. These reviews would all be classified as fresh, and the film would receive a misleadingly high score of 100% (The Terminator has a 100% rating, for example, while The Godfather does not). Let’s imagine another film receives all two out of four-star reviews. These would be classified as rotten, and the film would receive a rating of 0%, indicating one of the worst movies of all time. But the movie wouldn’t really be that bad.

According to the website Rotten Tomatoes, there are four types of movies: good-good movies, good-bad movies, bad-good movies, and bad-bad movies. These types can be identified using the Rotten Tomatoes score for each movie, particularly the relationship between the critics’ score and the audience’s score. Let me explain. Rotten Tomatoes is a website that collects movie reviews and assigns them a rating of either “fresh” (if the review is positive) or “rotten” (if the review is negative). It then calculates the percentage of fresh reviews and assigns this as a score to the movie. If the score is 60% or greater, the film itself is considered fresh, whereas if the score is lower than 60%, the film is rotten. This is a useful way of rating a movie, but there’s a problem here, too. Let’s imagine every reviewer gives a movie three out of four stars, indicating a good film but not a great one. These reviews would all be classified as fresh, and the film would receive a misleadingly high score of 100% (The Terminator has a 100% rating, for example, while The Godfather does not). Let’s imagine another film receives all two out of four-star reviews. These would be classified as rotten, and the film would receive a rating of 0%, indicating one of the worst movies of all time. But the movie wouldn’t really be that bad.