by Mark Harvey

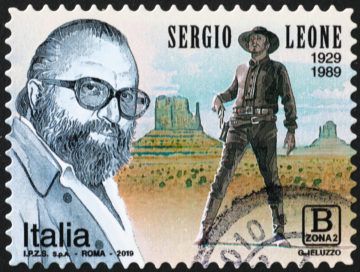

It’s hard to know what the old west was really like as we’ve been so inundated with Hollywood films depicting the west as an eternal gunfight between good guys and bad guys, cowboys and Indians, and the unshaven versus the upstanding townsfolk. Westerns have had an outsized impact on our understanding of the times and just a few directors shaped our grasp of that history more than any books ever written. In fact, some of the most popular and influential western films were directed by an Italian named Sergio Leone who was born in Rome in 1929, about 6,000 miles from where the fight at the OK Corral took place. Leone directed A Fistful of Dollars (Per un pugno di dollari, in Italian), For a Few Dollars More, and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly. Leone’s films popularized “spaghetti westerns,” so named because so many were being produced in Italy where it was cheaper to make movies. By some sort of alignment of the stars, Leone happened to be a childhood classmate of the great composer Ennio Morricone, who wrote over 400 movie scores. Morricone wrote the scores for several of Leone’s films, including the Dollars trilogy, and his music with the haunting, menacing whistles and twangy guitar guided Clint Eastwood on his adventures of killing lots of bad guys with greasy faces and half-chewed cheroots.

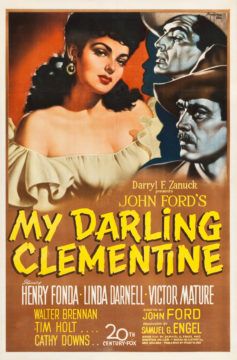

The director John Ford, born in Maine, made some of the most iconic westerns and one of his best, according to the critics, is My Darling Clementine. It was President Harry Truman’s favorite film and to be sure has a gripping plot and was beautifully filmed in black and white. While definitely more nuanced than Leone’s Dollar series, it still isn’t very nuanced. The black and white characters are as highly contrasted as the cinematography. In Clementine, The Earp brothers, good men trying to get their cattle to California to sell, exude wholesomeness, and the Clanton gang, bad men who steal their cattle, are furtive, shifty killers. No moral relativism here. The exception is Doc Holiday, portrayed as a hard-drinking man slowly dying of tuberculosis. In the film, Holiday somehow resists the advances of the beautiful “Chihuahua,” who serenades him in the cantina with a song that goes,

The director John Ford, born in Maine, made some of the most iconic westerns and one of his best, according to the critics, is My Darling Clementine. It was President Harry Truman’s favorite film and to be sure has a gripping plot and was beautifully filmed in black and white. While definitely more nuanced than Leone’s Dollar series, it still isn’t very nuanced. The black and white characters are as highly contrasted as the cinematography. In Clementine, The Earp brothers, good men trying to get their cattle to California to sell, exude wholesomeness, and the Clanton gang, bad men who steal their cattle, are furtive, shifty killers. No moral relativism here. The exception is Doc Holiday, portrayed as a hard-drinking man slowly dying of tuberculosis. In the film, Holiday somehow resists the advances of the beautiful “Chihuahua,” who serenades him in the cantina with a song that goes,

Oh the first kiss is always the sweetest

From under a broad sombrero

She sings the song while wearing the broadest sombrero you’ve ever seen and that Holliday can rebuff her beauty, tantalizing singing, and sombrero shows just how troubled and complex a character he is. I would have been reduced to putty faced with her charm and sombrero.

If you took the Sergio Leone or John Ford version of the old west, life would revolve around donning a serape, gathering up some men, jumping on horses, chasing down outlaws, a hell of a lot of squinting into the sun, a good amount of whiskey and probably never taking your spurs off —even during visits to the brothels. The saloons would be none too welcoming with high-stakes card games where winning the pot usually meant getting shot and bloodying the poor saloon keeper’s floor for the third time on a Friday night alone. Women would either be ladies of ill repute—soiled doves–named Pearl or Kitty, or pretty, virgin schoolteachers just getting off the train from back East to start a life in a desert town with other bonneted women and the creaky, annoying, nonstop sound of wagon wheels. Apart from racing across the plains on great horses, life in the old west, per western movies, didn’t look very fun.

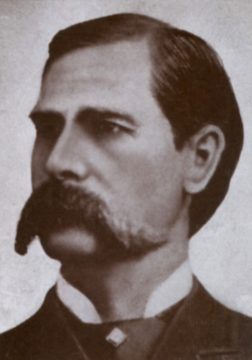

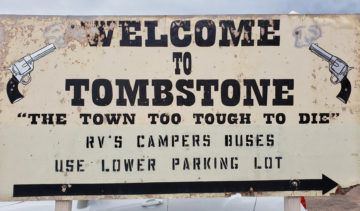

So how do we know what the old west was really like? There are some great memoirs from the late 1800s but thanks to the Internet we can also read newspapers from nearly every western town that had an operating paper in that era. If we’re going to pick a western town to explore its lesser-known side, Tombstone, Arizona, is a good one because it did have a lot of gunfights and outlaws, it was where the shootout at the OK Corral took place, Wyatt Earp was sheriff there for a spell, Doc Holliday practiced his dentistry and skills playing faro, and is the town that Ford’s Clementine is based on. Luckily Tombstone had a weekly newspaper named the Tombstone Epitaph (someone had a sense of humor in that dusty town) so with a little work a person can get a sense of the town. It takes a mighty poor social life or an unbalanced interest in the old west to spend evenings reading old copies of the Tombstone Epitaph online. I’ve combed through a few editions so you don’t have to.

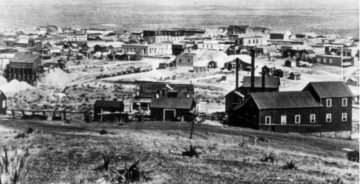

Tombstone, Arizona, is located in Cochise County just 30 miles north of the Mexican border. It was named after a silver mining claim made by one Ed Schieffelin. As the story goes, when Schiefflin told his army friend Al Sieber of his plans to search for silver in the hills east of the San Pedro River, Sieber said something worthy of a Sergio Leone movie: “The only rock you will find out there will be your own tombstone.” Sieber was likely referring to the danger of being killed by Apache Indians, who were making a heroic stand against white settlers moving into their traditional lands.

Schieffelin eventually did find silver and the town grew to 14,000 inhabitants when the area proved to be very rich in silver lodes. The town also attracted a lot of troublemakers, cattle thieves, and downright bad hombres as towns found on sudden riches are wont to do. In 1881, Wells Spicer, who became a judge in Tombstone, wrote, “Tombstone has two dance halls, a dozen gambling places and more than 20 saloons. Still, there is hope, for I know of two Bibles in town.”

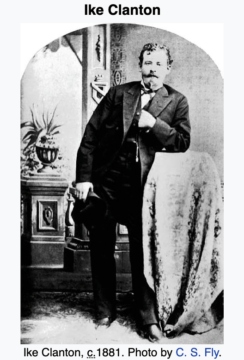

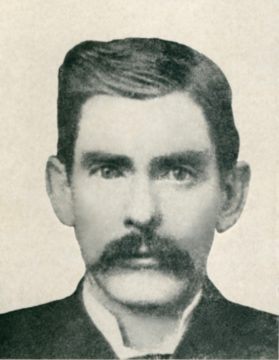

Perhaps the worst of the bunch living near Tombstone was the Clanton family who excelled at stealing cattle in Mexico, herding them back up into Arizona and adding them to their own herd. The Clantons also stole cattle from neighboring ranches and appear to have been a bullying family. A surviving studio photo of Ike Clanton, the family’s leader, shows a young man dressed immaculately in a three-piece suit, wearing a watch fob and a fastidious mustache. With his slightly cherubic face and dandy dress, Clanton looks more like a maître d’ at a western-themed restaurant than the gunslinging, cattle-thieving mob boss that he was.

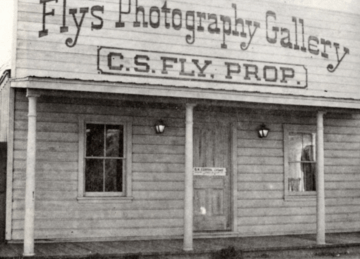

The photo of Clanton was taken either by Camillus Sydney Fly or his wife Mollie Fly, both accomplished photographers who ran Fly’s Photography Gallery in downtown Tombstone. That photo is a good point of departure to explore the real west versus the spaghetti western version. A movie made in Spain by an Italian director about gunslingers from 19th century Arizona is one way how we came to conceive of the west today, mostly because a movie about the laborious process of taking photos in that age would have been, well, laborious. But Fly’s pioneering work to document the Arizona Territory with primitive equipment was certainly more heroic and required more effort and art than stealing cattle in Mexico. What’s more, Fly’s later life would have made a good movie with a Morricone score to it. We’ll get to that.

To take a photo and then print it in a newspaper in the 1880s was a long unforgiving process that required heavy gear, precision, and patience. The technique at the time was to use glass plate negatives in what was called the collodion process. In 1864, John Towler, the publisher of The Silver Sunbeam described the process in 10 steps:

- Preparing the glass plate.

- Coating the prepared plate with collodion.

- Sensitizing the plate.

- Exposing the prepared plate in the camera.

- Developing the picture.

- Fixing the image.

- Drying the plate.

- Remove any particles which may be settled on the plate.

- Flow the plate with the “purest and most transparent crystal varnish, precisely in the same manner as the plate was covered with collodion

- Apply a dark background to the plate in the form of black velvet or paper.

The chemicals involved in the collodion process included silver nitrate, pyroxylin, zinc bromide, potassium bromide, and ammonium carbonate, among others. So imagine the dedication to their craft that CS and Mollie Fly must have had to procure those chemicals, cameras, and glass plates and then keep up an active photographic studio in the dusty town of Tombstone amid the gunfights and cattle thieving.

Even once a photo was taken using the glass plates, printing it in a newspaper was a difficult process. A skilled engraver would copy the photo on a metal plate and then that plate was used for the image in the paper.

The Flys lived a sometimes itinerant life trying to make a living with their photography and they also kept a boarding house in Tombstone. Their surviving photos were exquisite. The most famous of their photos were taken in March of 1886 by CS Fly when the Apache chief Geronimo offered to surrender to the US army in Cañon de los Embudos in the Sierra Madre Mountains of Mexico. Fly somehow got word of the proposed meeting between General Crook and Geronimo, loaded up his camera gear and glass plates onto pack horses, and rode 80 miles over several days with an assistant to witness and document the surrender. He convinced Crook to allow him to photograph the meeting which took place over three days in an encampment far from anything.

Although Geronimo was considered to be one of the fiercest warriors that ever lived, his reputation seemed to have no effect on Fly. In The Journal of Arizona History, Jay Van Orden writes that Fly “acted like a wedding photographer ordering [the apaches] to line up or move this way or that to obtain a preconceived composition.” Geronimo was deeply feared by both the Mexican army and the American army but Fly was fearless. His photos of Geronimo and the meeting were published a month later in Harpers Magazine.

The irony of the modern age is that today we can effortlessly take thousands of high-quality photos on phones the size of a deck of cards, but few of us have lives interesting or adventurous enough to merit thousands of photos. In the 1800s, pioneers lived lives that really did merit documentation but the process was so slow, expensive, and difficult that few photos were possible. Down the road there will be hundreds of millions of photos of influencers posing in front of the Sydney Opera House, doing a splayed jump on a beach in Costa Rica, or skiing in Vail—generally “living their best life”—but only a handful of photos of Geronimo or wagons on the Oregon Trail. Pity the archivist 100 years from now sorting through photos since the advent of the iPhone.

The famed shootout at the OK Corral (short for Old Kindersley Corral) took place in Tombstone five years before Fly shot his photos of Geronimo. And though he is seldom mentioned in the lore, Fly was a central figure in the shootout. To begin, one of the gunfighters, Doc Holliday, was a border in the Fly’s guesthouse as presumably was his then mistress, “Big Nose Kate.” (Given Holliday’s lightning-quick skills with a six-shooter, it’s a wonder he never shot anyone for calling his girlfriend that name.) And the fight didn’t actually take place in the corral, which was a nearby livery station. It took place right in front of the Fly’s photography studio. Why it became knowns as The Fight at the OK Corral might have to do with the idea that “The Fight in Front of the Fly’s Photography Studio” just doesn’t have the same ring to it.

The fight was the culmination of a long-simmering feud between two Clanton brothers and two McLaury brothers on one side, and three Earps and Doc Holliday on the other. The feud between the two groups involved various accusations of major stagecoach robberies, cattle thieving, and previous physical brawls. All accounts suggest that the men had a deep hatred of each other and that almost anything could have triggered the incident. The Clantons and the McLaurys were called cow-boys (with the hyphen as printed in the Epitaph) by Tombstone residents and the term had a very negative connotation of lawlessness and anti-social behavior. Ranchers in the area did not like being called cow-boys as it implied stealing cattle to build a herd.

Ironically, the ignition point that started the fight at the OK Corral came when Virgil Earp, then Tombstone’s city marshal, tried to enforce a city ordinance that outlawed the carrying of weapons within the city limits. Under Section 1, the ordinance said, “It is hereby declared unlawful to carry in the hand or upon the person or otherwise any deadly weapon within the limits of said city of Tombstone, without first obtaining a permit in writing.” Those entering Tombstone while carrying weapons, including Bowie knives, were supposed to check them into a hotel or a stable within a reasonable amount of time.

On October 26, 1881, Virgil Earp, who was the city Marshal, got word that two Clanton brothers and two McLaury brothers had entered the town armed and refused to store their weapons. Earp gathered his two brothers, Wyatt, and Morgan, as well as Doc Holliday to disarm the McLaurys and the Clantons. The Earps confronted the cow-boys in front of Fly’s studio and Virgil Earp, according to later testimony, said, “Throw up your hands, I want your guns.”

It’s hard to know who shot first in the gunfight. There were a few witnesses but lots of contradictory accounts. Virgil Earp stated that he only drew his pistol after Billy Clanton drew his. There was at least one horse in the mix, that of Tom McLaury, and Virgil said McLaury hid behind it while firing shots. According to testimony, Holliday had come heavily armed with a double-barreled shotgun and a nickel-plated pistol and did most of the shooting.

The Earps and Holliday were unquestionably better gunmen than the cow-boys. After the shooting, which lasted perhaps less than a minute, two Mclaurys were dead as well as Billy Clanton. Two Earps suffered bullet wounds, Holliday was barely grazed, and Wyatt was untouched.

The tough-talking Ike Clanton turned out to be a coward and immediately fled from the fight without firing a shot. He escaped into the Fly’s boarding house. And Tombstone’s eminent photographer, CS Fly, turned out to have more courage than some of the cow-boys. He immediately went out to the scene of the gunfight with a Henry rifle and disarmed the dying Billy Clanton.

Fly went on to become the county Sheriff in 1894 and served in that role until 1897.

That the tough town of Tombstone prohibited carrying weapons except for those quickly passing through, while today in all but three states, the open carry of weapons is allowed is another one of those modern ironies. You might reason that the number of gunfights in Tombstone forced the city elders to enact gun laws, but even the most famed shootout that ever happened in the old west when three men were shot dead and two more injured in front of the CS Fly Photography Studio, was by the scale of today’s shootings a minor skirmish. The 2017 shooting in Las Vegas killed 61 people when Stephen Paddock fired more than 1,000 shots from the 32nd floor of the Mandalay Hotel. But today in Las Vegas its perfectly legal to open-carry a firearm on the strip or throughout most of the rest of the town.

The newspapers from that era confirm some of the stereotypes of Leone’s and Ford’s films. There were a lot of gunfights, stagecoach robberies, and cattle stealing. But they mostly depict a much more interesting flavor with less of the stiffness, and far more absurdity. For instance, just two months after the shootout at the OK Corral, in the December 19, 1881, edition of the Tombstone Epitaph, there is a short instructional piece on “How to Shake Hands. The article begins, “There are only two or three people living now who can successfully shake hands.” It then gives a detailed explanation of how to shake hands the right way and the wrong way and is particularly detailed about how to shake hands with a lady:

If you are shaking hands with a lady, incline the head forward with a soft and graceful yet half timid movement, like a boy climbing a barbed wire fence with a fifty-pound watermelon. Look gently in her eyes with a kind of pleading smile, beam on her features a bright and winsome beam, say something that you have heard someone else say on similar occasions and in the meantime shake her hand in a subdued yet vigorous way, not as though you were trying to make a mash by pulverizing her fingers nor yet in too conservative a manner, allowing her hand to fall with a sickening thud when you let go.

Now that is a fine piece of advice for how to shake hands with a lady and since it was printed so prominently in the Epitaph, obviously a needed piece of advice for men when they weren’t out stealing cattle or bounty hunting.

The Epitaph is also filled with announcements about Christmas parties for children, ads for fine wines brought from Europe (now that doesn’t ever come out in popular westerns) concoctions to help cure tuberculosis, and some of the same sort of dubious promises we see today of the healing qualities of magnets, advertised to solve everything from kidney stones to heart disease.

Today Tombstone has about 1,500 residents and appears to have become a touristy shadow of its past. There are gunfight reenactments at noon, 2:00 pm, and 3:30 pm. The gunfight at the OK Corral still appears to be the main draw to the town.

It’s hard to judge the town today, having never been there, but I think it’s safe to say John Ford or Sergio Leone would have looked elsewhere for a dramatic story. The town’s strict and stodgy ordinances alone are enough to have scared off the likes of a Doc Holliday, a Wyatt Earp, or a CS Fly.

The regulations on riding horses in Tombstone found on the town’s website are particularly restrictive and burdensome. Section C of the rules and regulations for Equine Use and Control reads, “Riding two (2) or more persons on a single animal is prohibited, except by special permission of the enforcement officer.” Section I of the regulations reads, “Equine shall not be allowed to run or cantor within the limits of the Schieffelin historic district.”

The town that was once home to the Earp brothers, Doc Holliday, and CS Fly now has a city code that says you can’t ride a horse with more than one person on it and you can’t gallop your horse in town. You might not be killed in a gunfight in Tombstone nowadays, but you might die from its suffocating regulations.

The town that was once home to the Earp brothers, Doc Holliday, and CS Fly now has a city code that says you can’t ride a horse with more than one person on it and you can’t gallop your horse in town. You might not be killed in a gunfight in Tombstone nowadays, but you might die from its suffocating regulations.