by Raji Jayaraman

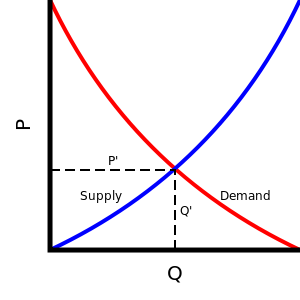

Every Econ 101 student learns the basic model of demand and supply. It’s pretty straight forward. Picture a graph with the price of a product or service on the vertical axis and the quantity supplied and demanded on the horizontal axis. There are two curves drawn on this graph: the demand curve and the supply curve. The demand curve is downward sloping because as prices decrease, consumers are willing to buy more. The supply curve is upward sloping because producers are willing to supply more when they are paid more. The “competitive equilibrium price” of the product or service is where supply equals demand: two curves intersect. When prices are higher than the equilibrium price, supply is greater than demand: there is “excess supply”. This makes sense: at higher prices, suppliers are going to be happy to sell more, but consumers aren’t willing to buy as much.

Every Econ 101 student learns the basic model of demand and supply. It’s pretty straight forward. Picture a graph with the price of a product or service on the vertical axis and the quantity supplied and demanded on the horizontal axis. There are two curves drawn on this graph: the demand curve and the supply curve. The demand curve is downward sloping because as prices decrease, consumers are willing to buy more. The supply curve is upward sloping because producers are willing to supply more when they are paid more. The “competitive equilibrium price” of the product or service is where supply equals demand: two curves intersect. When prices are higher than the equilibrium price, supply is greater than demand: there is “excess supply”. This makes sense: at higher prices, suppliers are going to be happy to sell more, but consumers aren’t willing to buy as much.

Economic conservatives often apply this logic to justify their opposition to a minimum wage. The argument goes like this. Minimum wages mandate that the price of labour be set above the market wage. At the new, higher wage there are more people willing to work and fewer jobs to go around because hiring a worker is now more costly to employers. In other words, there will be an excess supply of labour. Another way of saying this is that there’s going to be more (involuntary) unemployment.

Now, of course there are many excellent reasons to want to raise the minimum wage, none which have anything to do with economics. Trying to ensure that low-wage workers are paid decently is important if you care about things like equity, human decency, and fairness. But if my support for minimum wages rested on my commitment to social justice, the prospect of this policy instrument causing a dramatic increase in unemployment would give me pause. It’s hard to maintain the moral higher ground when my favoured policy improves the wages of those who are lucky enough to have a job but drives countless others into unemployment. Read more »

Sughra Raza. First Snow 2022.

Sughra Raza. First Snow 2022. On the anniversary of the attempt by Donald Trump and some of his supporters to subvert the 2020 US presidential election, Joe Biden denounced those who “place a dagger at the throat of democracy.” To which one can only say: About bloody time! The threat posed by Trump and the Republican party to America’s democratic institutions–highly imperfect though they are–is so obvious that anyone who has a bully pulpit should be pounding out a warning at every opportunity.

On the anniversary of the attempt by Donald Trump and some of his supporters to subvert the 2020 US presidential election, Joe Biden denounced those who “place a dagger at the throat of democracy.” To which one can only say: About bloody time! The threat posed by Trump and the Republican party to America’s democratic institutions–highly imperfect though they are–is so obvious that anyone who has a bully pulpit should be pounding out a warning at every opportunity. A large number of jobs exist not because they create economic value but because they make business sense given the institutions we have – customer expectations, bureaucratic regulations, and so on. They do not solve a real problem but a fake problem created by inefficient institutions. They therefore do not make our society better off but rather they represent a great cost to society – of many people’s time being expended on something fundamentally pointless instead of something worthwhile. One way of spotting such anti-jobs is to compare staffing in the same industry across different countries. US supermarkets employ people just to greet customers and bag groceries, for example, which would seem a ridiculous waste of time in most of the world. In Japan one can find people standing in front of road construction waving a flag (they are replaced with mechanical manikins on nights and weekends).

A large number of jobs exist not because they create economic value but because they make business sense given the institutions we have – customer expectations, bureaucratic regulations, and so on. They do not solve a real problem but a fake problem created by inefficient institutions. They therefore do not make our society better off but rather they represent a great cost to society – of many people’s time being expended on something fundamentally pointless instead of something worthwhile. One way of spotting such anti-jobs is to compare staffing in the same industry across different countries. US supermarkets employ people just to greet customers and bag groceries, for example, which would seem a ridiculous waste of time in most of the world. In Japan one can find people standing in front of road construction waving a flag (they are replaced with mechanical manikins on nights and weekends).

At ISI we were assigned statistical assistants who’d take our large data analysis jobs to the IBM computer at the Planning Commission, but for relatively small jobs they’d do the calculations themselves by furiously rotating the handles of the small Facit mechanical calculator they each had, you could literally hear the noise of ‘data crunching’. This was before electronic desk calculators came to Indian institutions. I remember buying a small Texas Instruments calculator in a short trip abroad and was quite impressed by its capacity; and I told TN that I did not need to learn the operation of Facit machines, which I saw him cranking all the time. (This reminds me of a British economist, Ivor Pearce, who told me that just before the War he used to work for an accounting firm where they had not yet heard of log tables; he said he finished the whole day’s work in just an hour by using the log table and read books in his office the rest of the time). Of course, I am told today our tiny laptops/smartphones contain computing capacity million times larger than the biggest IBM machines in India at that time.

At ISI we were assigned statistical assistants who’d take our large data analysis jobs to the IBM computer at the Planning Commission, but for relatively small jobs they’d do the calculations themselves by furiously rotating the handles of the small Facit mechanical calculator they each had, you could literally hear the noise of ‘data crunching’. This was before electronic desk calculators came to Indian institutions. I remember buying a small Texas Instruments calculator in a short trip abroad and was quite impressed by its capacity; and I told TN that I did not need to learn the operation of Facit machines, which I saw him cranking all the time. (This reminds me of a British economist, Ivor Pearce, who told me that just before the War he used to work for an accounting firm where they had not yet heard of log tables; he said he finished the whole day’s work in just an hour by using the log table and read books in his office the rest of the time). Of course, I am told today our tiny laptops/smartphones contain computing capacity million times larger than the biggest IBM machines in India at that time.

Sughra Raza. Rainy Reflection Self-portrait for 2022.

Sughra Raza. Rainy Reflection Self-portrait for 2022.