by Danielle Spencer

The theme of home—as a topic, question—is woven throughout Siri Hustvedt’s excellent new essay collection, Mothers, Fathers, and Others. In the first essay, “Tillie,” about her grandmother, Hustvedt also recalls her grandfather, Lars Hustvedt, who was born and lived in the United States, and first traveled to his own father’s home in Voss, Norway, when he was seventy years old. “Family lore has it that he knew ‘every stone’ on the family farm, Hustveit, by heart,” Hustvedt writes. “My grandfather’s father must have been homesick, and that homesickness and the stories that accompanied the feeling must have made his son homesick for a home that wasn’t home but rather an idea of home.”

The theme of home—as a topic, question—is woven throughout Siri Hustvedt’s excellent new essay collection, Mothers, Fathers, and Others. In the first essay, “Tillie,” about her grandmother, Hustvedt also recalls her grandfather, Lars Hustvedt, who was born and lived in the United States, and first traveled to his own father’s home in Voss, Norway, when he was seventy years old. “Family lore has it that he knew ‘every stone’ on the family farm, Hustveit, by heart,” Hustvedt writes. “My grandfather’s father must have been homesick, and that homesickness and the stories that accompanied the feeling must have made his son homesick for a home that wasn’t home but rather an idea of home.”

Homesick for a home that wasn’t home but rather an idea of home. Yet home is always an idea of home, even when it is indeed a home we have experienced. Lars’ memory evinces philosopher Derek Parfit’s discussion of “q-memory”—a memory of an experience which the subject didn’t experience. Rachael’s implanted “memories” in Blade Runner are q-memories (and perhaps Deckard’s are as well, at least in the Director’s Cut.) According to Parfit, the notion that I am the person who experienced my memory is an assumption I make simply because I presume that I don’t have q-memories. Thus

on our definition every memory is also a q-memory. Memories are, simply, q-memories of one’s own experiences. Since this is so, we could afford now to drop the concept of memory and use in its place the wider concept q-memory. If we did, we should describe the relation between an experience and what we now call a “memory” of this experience in a way which does not presuppose that they are had by the same person.

As André Aciman puts it, “things always seem, they never are.” In his essay “Arbitrage,” he describes his own experience of being, in Hustvedt’s words, homesick for a home that wasn’t home but rather an idea of home—or perhaps moreso in his case, homesick for missing home. Read more »

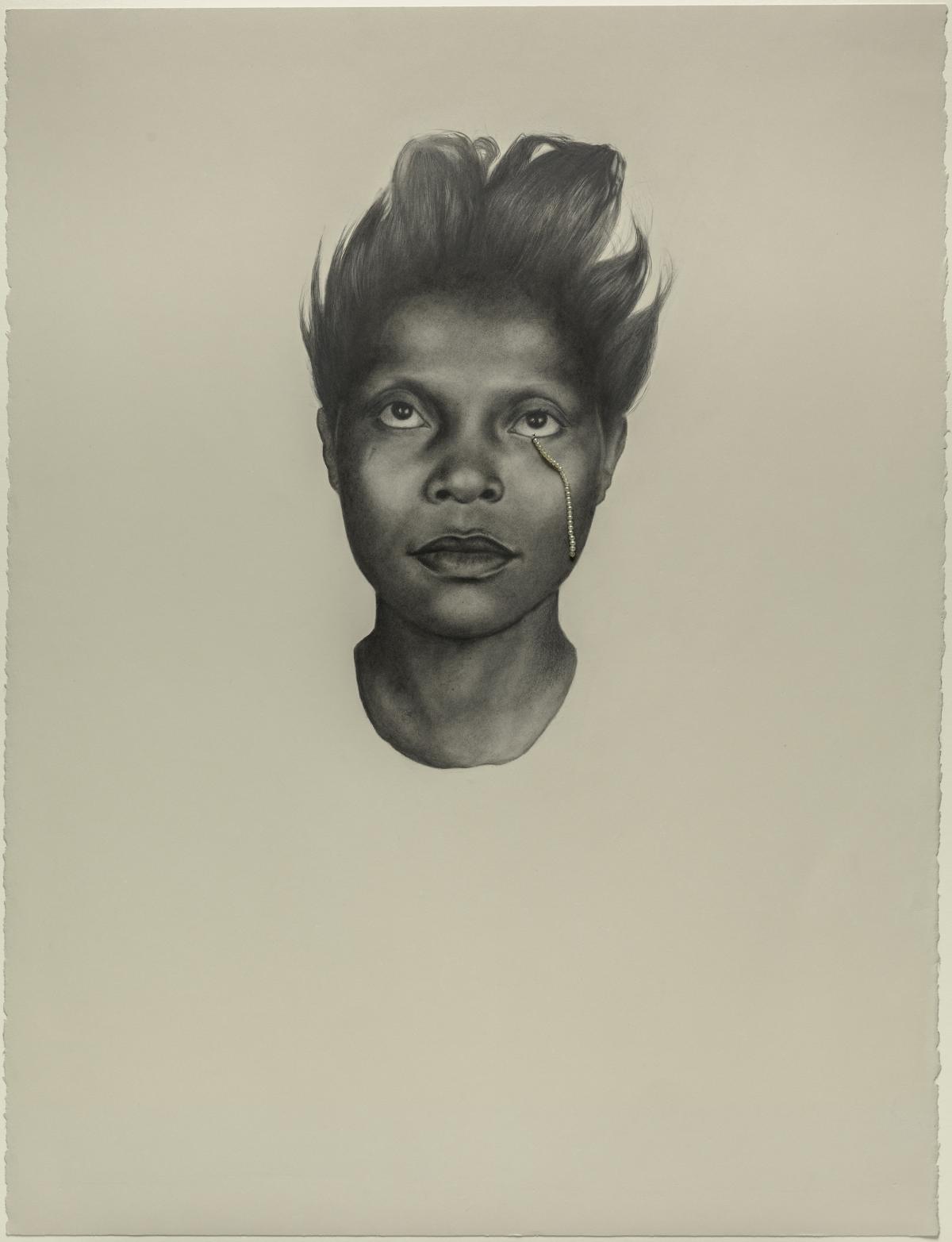

Sughra Raza. Inside Out, Boston, 2021.

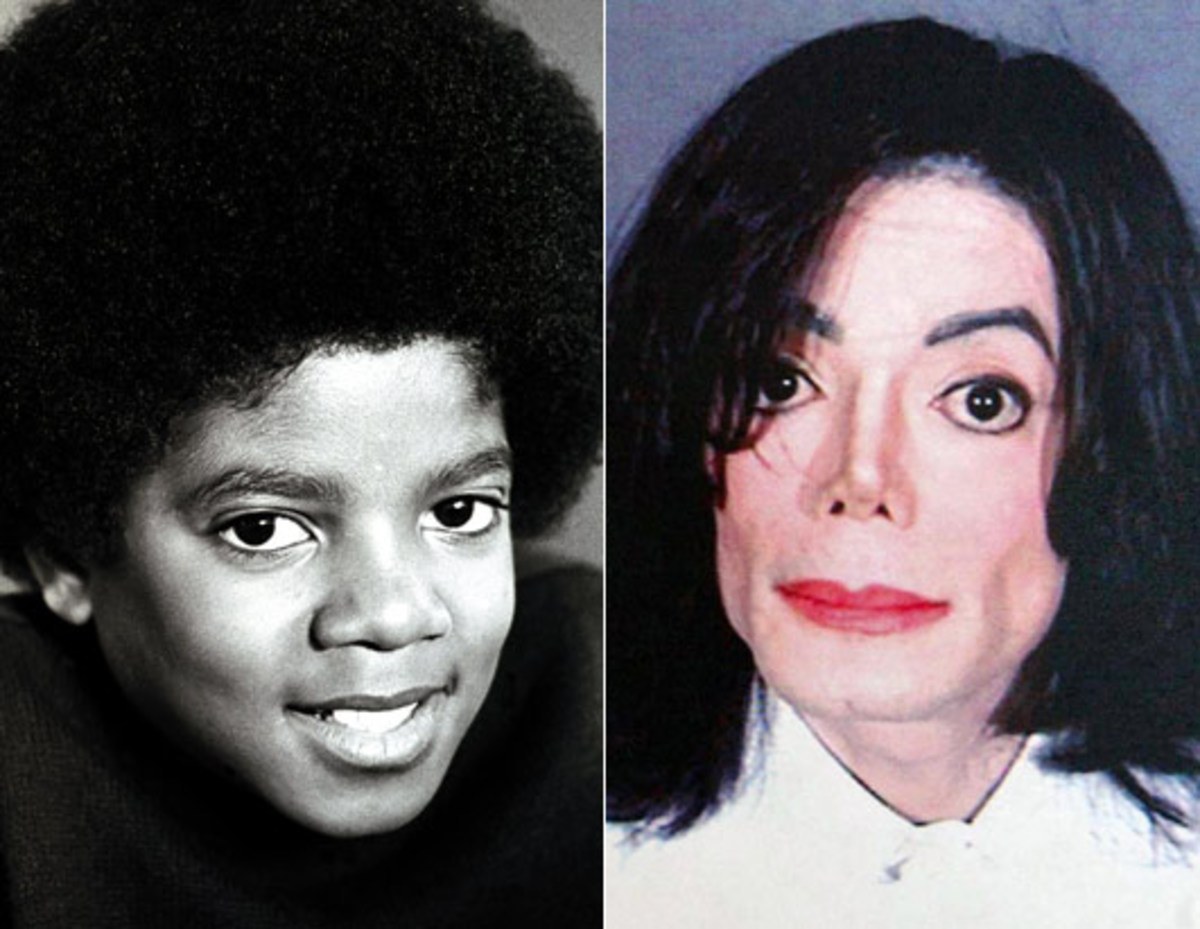

Sughra Raza. Inside Out, Boston, 2021. Over the course of more than a decade, Michael Jackson transformed from a handsome young man with typical African American features into a ghostly apparition of a human being. Some of the changes were casual and common, such as straightening his hair. Others were the product of sophisticated surgical and medical procedures; his skin became several shades paler, and his face underwent major reconstruction.

Over the course of more than a decade, Michael Jackson transformed from a handsome young man with typical African American features into a ghostly apparition of a human being. Some of the changes were casual and common, such as straightening his hair. Others were the product of sophisticated surgical and medical procedures; his skin became several shades paler, and his face underwent major reconstruction.

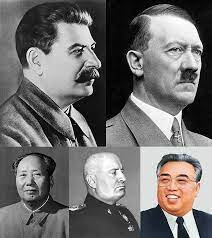

In this oft-reprinted quote from Hannah Arendt’s seminal work The Origins of Totalitarianism, many 21st century readers, particularly those engaged in pro-democracy movements in the United States and abroad, see Donald Trump and the emergent totalitarian formation of Trumpism sewn piecemeal onto the template that she constructed whole cloth from Hitler and Stalin’s political regimes. Although Trump hasn’t yet matched the political power, penchant for violence, or historical significance of Hitler or Stalin, he has made clear his disdain for democracy and exhibits a desire and willingness to use his power and violence to undo its institutional structures. For readers who are encouraged by the emergence of Trumpism and excited by its promise to make America great again, which includes inciting nationalistic pride, putting America’s interests first ahead of global concerns, policing public school curriculum for progressive ideological biases, packing the courts with sympathetic ideologues, and using banal procedural rules to derail the spirit of democratic negotiation and compromise then her work may provide you a cautionary tale regarding the potential implications of delivering on those promises.

In this oft-reprinted quote from Hannah Arendt’s seminal work The Origins of Totalitarianism, many 21st century readers, particularly those engaged in pro-democracy movements in the United States and abroad, see Donald Trump and the emergent totalitarian formation of Trumpism sewn piecemeal onto the template that she constructed whole cloth from Hitler and Stalin’s political regimes. Although Trump hasn’t yet matched the political power, penchant for violence, or historical significance of Hitler or Stalin, he has made clear his disdain for democracy and exhibits a desire and willingness to use his power and violence to undo its institutional structures. For readers who are encouraged by the emergence of Trumpism and excited by its promise to make America great again, which includes inciting nationalistic pride, putting America’s interests first ahead of global concerns, policing public school curriculum for progressive ideological biases, packing the courts with sympathetic ideologues, and using banal procedural rules to derail the spirit of democratic negotiation and compromise then her work may provide you a cautionary tale regarding the potential implications of delivering on those promises.

My name is Sarah Firisen, and I’m 5ft 2 inches tall and work in software sales. But I’m also, or used to be, Bianca Zanetti, a 5ft 9 size 0 (which I’m also not), fashion designer and proprietor of a chain of stores, Fashion by B. No, I’m not bipolar. Bianca Zanetti is my Second Life avatar.

My name is Sarah Firisen, and I’m 5ft 2 inches tall and work in software sales. But I’m also, or used to be, Bianca Zanetti, a 5ft 9 size 0 (which I’m also not), fashion designer and proprietor of a chain of stores, Fashion by B. No, I’m not bipolar. Bianca Zanetti is my Second Life avatar.

The Naxalite phase in Bengal was a short, tragic chapter in politics, but in Bengal’s cultural-emotional life its implications were deeper, and reflected in its literature (and films)—most poignantly yet forcefully captured by the writer Mahshweta Devi, one of Bengal’s most powerful political novelists. Again and again in the 20th century some of Bengali youth have been fascinated by the romanticism of revolutionary violence–as was the case in the early decades in the freedom struggle against the British (I have earlier mentioned about my maternal uncle caught in its vortex), then again in the 1940’s when the sharecroppers’ movement (called tebhaga) was soon followed by a period of communist insurgency in 1948-50, and then in the Naxalite movement of the late 60’s and early 70’s.

The Naxalite phase in Bengal was a short, tragic chapter in politics, but in Bengal’s cultural-emotional life its implications were deeper, and reflected in its literature (and films)—most poignantly yet forcefully captured by the writer Mahshweta Devi, one of Bengal’s most powerful political novelists. Again and again in the 20th century some of Bengali youth have been fascinated by the romanticism of revolutionary violence–as was the case in the early decades in the freedom struggle against the British (I have earlier mentioned about my maternal uncle caught in its vortex), then again in the 1940’s when the sharecroppers’ movement (called tebhaga) was soon followed by a period of communist insurgency in 1948-50, and then in the Naxalite movement of the late 60’s and early 70’s.

Whitfield Lovell. Kin XLV (Das Lied von der Erde), 2011.

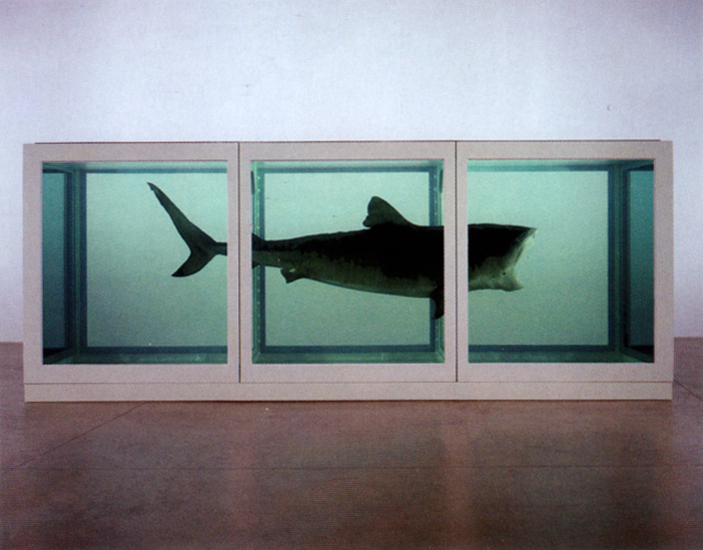

Whitfield Lovell. Kin XLV (Das Lied von der Erde), 2011. Not long ago, having steeled myself for the read-through of yet another dry but informative assessment of the body’s immune response to Covid 19 and her variant offspring, I was pleasantly surprised to find myself being dragged into a barbaric tale of murder and mayhem, full of gory details and dire strategies.

Not long ago, having steeled myself for the read-through of yet another dry but informative assessment of the body’s immune response to Covid 19 and her variant offspring, I was pleasantly surprised to find myself being dragged into a barbaric tale of murder and mayhem, full of gory details and dire strategies. We tell ourselves stories in order to live.

We tell ourselves stories in order to live.