by Bill Benzon

About a month ago Tyler Cowen posed the following question at Marginal Revolution, a blog he runs with along with his collegue Alex Tabarrok: Why has classical music declined? If you do a general web-search on that question you’ll see that it’s a popular topic. The ensuing discussion has had 210 remarks so far. That’s a lot, especially when you consider that Marginal Revolution centers on economics and closed allied social sciences, though Cowen does comment on the arts as well. Some responses are longish, somewhat detailed, and knowledgeable. Most are relatively brief. On the whole the quality of the discussion is high, but scattered, which is to be expected on the web.

Cowen posed the question in response to a request from one of his readers, Rahul, who had asked:

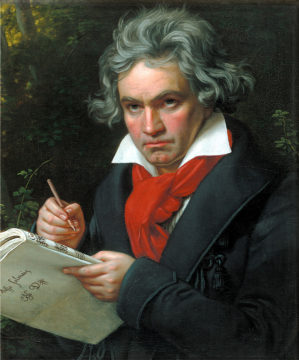

In general perception, why are there no achievements in classical music that rival a Mozart, Bach, Beethoven etc. that were created in say the last 50 years?

Cowen offered several observations of his own. Here’s the first:

The advent of musical recording favored musical forms that allow for the direct communication of personality. Mozart is mediated by sheet music, but the Rolling Stones are on record and the radio and now streaming. You actually get “Mick Jagger,” and most listeners prefer this to a bunch of quarter notes. So a lot of energy left the forms of music that are communicated through more abstract means, such as musical notation, and leapt into personality-specific musics.

Yikes! From Mozart to the Rolling Stones, that’s quite a lot of musical territory – one reason, perhaps, that the discussion was scattered.

In this piece I treat the discussion as a collection of dots. I draw lines between some of them and color in some of the shapes that emerge.

What music are we talking about?

Early last year Dr. Bjorn Mercer published a short article in which he listed the composers whose works appeared in concert most frequently from 2015 to 2019. Here are the top seven: Ludwig van Beethoven, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Johann Sebastian Bach, Johannes Brahms, Franz Schubert, Pytor Tchaikovsky, and Robert Schumann. The first three are sometimes informally known as the “Big Three.” All of belong to what is sometimes known as common practice period of European art music, running from about 1650 to 1900. All of them except Bach and Mozart are in the 19th century. About a decade ago the London Philharmonic issued a collection of The 50 Greatest Pieces of Classical Music. All but eight of those pieces were written before 1900.

That, I take it, is the body of music we’re talking about.

The musical techniques developed in this period have not disappeared. They are alive and well in various places. Thus a number of Cowen’s discussants mentioned films (e.g. Gary Arndt, Hazel Meade, and Steve Sailer), acknowledging that in that setting the music is subordinated to the film narrative. Jazz musician Ethan Iverson has an interesting piece, Theory and European Classical Music, where, among other things, he quotes 18 jazz pianists on the the classical music they practiced and studied. My favorite statement is from Sun Ra: “The composers I studied were Chopin, Rachmaninoff, Scriabin, Schoenberg, Shostakovich, the whole gamut. I think I studied everything at that school except farming.”

That those musical techniques survive is not, of course the issue. What seems to be at issue is the fact the works from the common practice period don’t seem to be as important in musical life as they once were and the fact that stand-alone works in those styles are no longer written, performed, and recorded.

The history of the common practice period is generally written as a succession of styles: Renaissance, Baroque, Classical, Romantic, and Impressionist. This is mentioned in the discussion of Cowen’s post (Joe Wiedemann) but not much discussed, perhaps because such discussion quickly wades into the technical and quasi-technical weeds of music theory. These styes have in common something called tonality (Wikipedia): “the arrangement of pitches and/or chords of a musical work in a hierarchy of perceived relations, stabilities, attractions and directionality.” As we move from style to the next new ways of exploiting tonality are invented and exploited. By the end of the 19th century composers had stretched tonality to the limit. Other devices had to be found for organizing composition and performance.

But composers didn’t stop working in (what we have come to think of as) the classical tradition: Schoenberg, Berg, Stravinsky, Shostakovich, Ravel, Prokoviev, Bartok, Ives, and Copeland, to name a few from the first half of the 20th century. Their music is performed and recorded, but not so often as work from the common practice period. Perhaps it’s not as good – though that brings up the issue of quality, which I’m going to gloss over for the purposes of this piece, but perhaps the fact that it isn’t cut from the cloth of common practice is itself sufficient explanation. Some of that music is “difficult” and requires one to listen to music in new ways. For whatever reason people aren’t willing or able to exert the effort. Thus some of Cowen’s discussants mentioned the decline of music education (Dana Gioia, Aleksey Nikolsky).

From Mozart to the Rolling Stones

Let’s turn to Cowen’s comment, which takes us beyond the classical tradition. The comment has two aspects: historical sweep, and style. Let’s start with the second.

Tyler glosses the contrast between Mozart and the Rolling Stones as a contrast between notation and personality. I’m not quite sure what to make of personality in this context. A commenter posting as However notes:

Lisztomania or Liszt fever was the intense fan frenzy directed toward Hungarian composer Franz Liszt during his performances. This frenzy first occurred in Berlin in 1841 and the term was later coined by Heinrich Heine in a feuilleton he wrote on April 25, 1844, discussing the 1844 Parisian concert season. Lisztomania was characterized by intense levels of hysteria demonstrated by fans, akin to the treatment of celebrity musicians today – but in a time not known for such musical excitement.

I’m not sure what However had in mind in the case of Mozart, but Liszt seems to have been a charismatic performer who knew how to play to his audience. His performances would have been based on notated music. Notation didn’t seem to hinder Liszt from personal expression.

Consider a more recent performer, one whose career overlaps a bit with Mick Jagger’s, Frank Sinatra. Just about every song Sintra performed was expressed in musical notation before Sinatra performed it. Sinatra was hardly the only popular and charismatic performer who relied on music that was expressed in notation before it was performed. Such performers are legion.

But notation certainly is important, but not much as a means of communicating to an audience, as Cowen’s comment would seem to imply. It’s important as a means of organizing musical material. Without it the evolution of music in the common practice period would have been impossible. Notation allows for the careful organization of relative large ensembles, from 10s to even 100s of musicians, and for precise formal control of musical devices in works requires 10s of minutes to over an hour of performance time.

Once recording and broadcast technology was developed performances of all kinds could be recorded and broadcast and that was certainly an important development. Before the 20th century musical performance had to be experienced in person. After World War I recording and radio broadcast became important means of communicating music. This technology also changed the nature of live performance, especially vocal performance. Sinatra’s vocal style, for example, would have been confined to very small venues without amplifcation. Amplication allowed him to reach audiences of 100s and 1000s of people in live performance.

Given that, and much I haven’t mentioned, though, I want to switch gears and take up the matter of historical sweep. How did we get from Mozart in the 18th century to the Rolling Stones in the 20th and 21st centuries? It’s not a line of direct nor even oblique cultural descent. The Stones are in a line of development that first crystalized in America in the 1950s, rock and roll, where Chuck Berry proclaimed “Roll Over, Beethoven” (1956), punctuating cultural confluence and conflict that had been raging for half a century and more.

We can trace rock and roll back through jump bands and swing combos to early jazz and blues, which then disperse into the 19th century, where minstrelsy emerged as a major form of mass entertainment. Minstrelsy involved the intermingling of musical devices from techniques from both European and West African cultures, thus implicating a large swath of historical forces and events.

The first quarter of the 20th century saw the migration of Blacks out of the South to the North, Midwest, and West. At the same time recording and radio allowed music to spread beyond the geographical locus of musical performers. Musicians could learn from performers they didn’t see in live performers.

The emergence of African-American musical styles was both exciting and quite contentious. Not only did the confluence and conflict between jazz/swing/blues vs. the long-hair and high-brow classics take place on the ground, but showed in films and cartoons and cartoons as well. We had Gershwin and Broadway and Armstrong, Crosby, and Sinatra figuring out how to adapt singing style to microphones and Amplification.

Harry James betwixt and between

Let’s look at a musical clip from one of these films, Do You Love Me, from 1946. Here’s the Wikipedia’s plot summary:

Jimmy Hale (Dick Haymes) is a successful singer. He chases Katharine “Kitten” Hilliard (Maureen O’Hara), a prim, bespectacled music school dean who, after traveling to the big city, transforms herself into a desirable, sophisticated lady. Jimmy isn’t the only one eager to win Katharine’s affections: it turns out that the smooth-as-silk trumpeter and bandleader Barry Clayton (Harry James) has designs on Katharine as well.

It’s squares vs. hep cats all tangled up in romance.

It’s a performance by Harry James, who played the role of Barry Clayton, that interests me. James was a trumpet player and band leader who was important in the 1930s and 1940s, though he continued performing well into the 1970s. He performed in both jazz and more popular styles. He had superb ‘legit’ technique but also had the approval of Louis Armstrong, whom he idolized.

In this clip James performs an absurd arrangement of W. C. Handy’s “St. Louis Blues,” one of the best-known tunes it jazz and pop. It had been recorded many times by many artists, including Handy himself, the Original Dixieland Jazz Band, Bessie Smith with Louis Armstrong, Fats Waller, Cab Calloway, Rudy Vallee (the sheet music with his face on the front includes ukulele tablature), Bing Crosby with Duke Ellington, Benny Goodman, Django Reinhardt, Guy Lombardo, and on and on – you get the idea. The audience knows that “St. Louis Blues” is not the kind of song that goes with a symphony orchestra sitting in front of classical pillars.

This is not great music. But it is well-crafted and highly polished. Such arrangements were served up in movie after movie by staff arrangers. This is routine musical craftsmanship of a high order.

The arrangement begins with a legit introduction where the strings and brass play two phrases from “St. Louis Blues” in a straight, almost march-like, style without a hint of swing. This quickly gives way to a clarinet melody (c. 0.17) that drops down low and works its way up in a series of arpeggios – I can’t help but think this is a sly reference to and revision of the clarinet line that opens George Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue.” This quickly (0.27) gives way to a fast punchy orchestral passage culminating in a brass fanfare (0.32) that builds to a climax, and then stops (0.37) and drops you over the edge of a cliff, as you didn’t see it coming.

We’ve been set up.

James turns around, picks up his trumpet, and digs deep into nasty blusey jazz trumpet (0.40). Notice how he bends his notes, plays notes with valves only half depressed, and throws in “shakes,” jazz ornaments that are a bit like trills, but utterly different in that they are rough while trills are delicate. This is jazz trumpet technique that’s not taught in conservatories, at least not in those days. That band, for that’s what the orchestra has become, a jazz band, plays a slinky vamp to back him up. That goes on until 1.34.

At this point we’ve been presented with two (opposing) musical worlds, the classical world (played for laughs), and jazz (played with utter sincerity). The rest of the arrangement plays in the space opened up between them.

James lowers his trumpet and returns to conduct the orchestra, which goes into a straight rendition of the blues theme that opened the piece, played in sweeping romantic fashion by the strings. We get through 12 bars of that and have another change of pace. Starting at roughly 2:16 the strings take up the other blues theme, straight time, played pizzicato, as unjazzy a sound as you could imagine. They finish the 12-bars and the brass comes crashing in at 2:33. Now the violins switch to their bows playing rapid figures of the sort I associate with bustling street scenes where people are rushing about doing things. James comes in playing rapid trumpet figures in a complementary fashion. This is 19th century (classical) virtuoso showpiece material with slight swing inflections. We’re poised between the legit and jazz musical worlds – a very American bit of stylistic juggling.

Trumpeting brass figures signal a change (2:51) and we move to a more or less standard big-band shout chorus where the ensemble, sans strings, plays a thick texture of backing riffs while the soloist wails over the top. James stops playing and the strings join in (3:29) and, once things get moving, James returns and puts a cherry on top (3:42), riding it for a few bars, pausing for a pair of simple two-note trumpet figures, and closing it out with an ascending triplet run (3:53) leading to the final chords.

One might be tempted to quip that with music like that, we’re lucky that classical music survives at all. Though this pastiche is as far from Mozart as it is from the Rolling Stones, it is on the road the runs between the two. It is by no means the strangest or cheesiest of the hundreds of thousands of performances in that territory.

What happened?

What happened to classical music? It settled into history. While those 18th and 19th century compositions are no longer as central to Western cultural life as they once were. But the musical devices and techniques have survived and become common practive in many musical forms and the compositions themselves continue to be heard and enjoyed.

Things change. Cowen mentioned that “two World Wars ripped out the birthplaces of so much wonderful European culture.” That is one kind of change. The migration of Black Americans out of the South in the late 19th and early 20th centuries is another kind of change. The development of recording and broadcast technology is still another kind of change. Why should classical music be impervious to such forces?