by Usha Alexander

[This is the sixteenth in a series of essays, On Climate Truth and Fiction, in which I raise questions about environmental distress, the human experience, and storytelling. All the articles in this series can be read here.]

Was it inevitable, this ongoing anthropogenic, global mass-extinction? Do mass destruction, carelessness, and hubris characterize the only way human societies know how to be in the world? It may seem true today but we know that it wasn’t always so. Early human societies in Africa—and many later ones around the world—lived without destroying their environments for long millennia. We tend to write off the vast period before modern humans left Africa as a time when “nothing much was happening” in the human story. But a great deal was actually happening: people explored, discovered, invented, and made decisions about how to live, what to eat, how to relate to each other; they observed and learned from the intricate and changing life around them. From this they fashioned sense and meaning, creative mythologies, art and humor, social institutions and traditions, tools and systems of knowledge. Yet it’s almost as though, if people aren’t busily depleting or destroying their local environments, we regard them as doing nothing.

Was it inevitable, this ongoing anthropogenic, global mass-extinction? Do mass destruction, carelessness, and hubris characterize the only way human societies know how to be in the world? It may seem true today but we know that it wasn’t always so. Early human societies in Africa—and many later ones around the world—lived without destroying their environments for long millennia. We tend to write off the vast period before modern humans left Africa as a time when “nothing much was happening” in the human story. But a great deal was actually happening: people explored, discovered, invented, and made decisions about how to live, what to eat, how to relate to each other; they observed and learned from the intricate and changing life around them. From this they fashioned sense and meaning, creative mythologies, art and humor, social institutions and traditions, tools and systems of knowledge. Yet it’s almost as though, if people aren’t busily depleting or destroying their local environments, we regard them as doing nothing.

Of course, it is a normal dynamic of evolution that one species occasionally will outcompete another and drive it toward extinction. But for most of their time on Earth, human beings were not having an outsized, annihilating effect on the life around them, rather than co-evolving with it. That evolution was at least as much cultural as it was a matter of flesh. What people consumed, how they obtained it, and how quickly they used it up has always played a role in the stability and evolution of any ecosystem of which humans were a part. How fast human populations grew, how they sheltered, what they trampled and destroyed or nourished and promoted—all of this affected their environment. Naturally, their interactions with the environment were always driven by what they wanted. And what people want is intimately driven by what they believe, as in the stories they tell themselves. One thing we can safely presume: those who understood their own social continuity as contingent upon that of their environment weren’t telling the same stories we tell today. Read more »

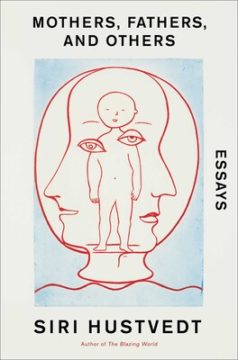

The theme of home—as a topic, question—is woven throughout Siri Hustvedt’s excellent new essay collection,

The theme of home—as a topic, question—is woven throughout Siri Hustvedt’s excellent new essay collection,  Sughra Raza. Inside Out, Boston, 2021.

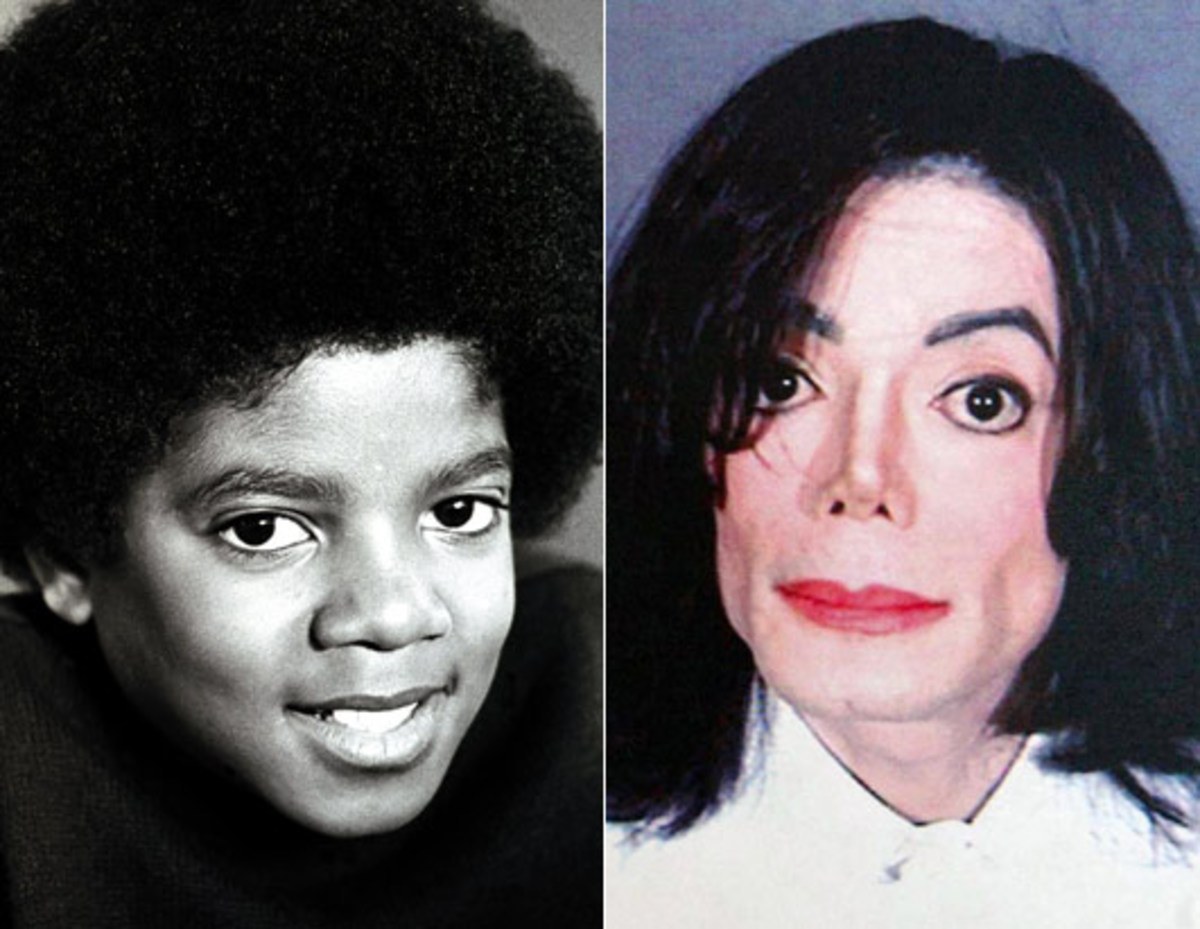

Sughra Raza. Inside Out, Boston, 2021. Over the course of more than a decade, Michael Jackson transformed from a handsome young man with typical African American features into a ghostly apparition of a human being. Some of the changes were casual and common, such as straightening his hair. Others were the product of sophisticated surgical and medical procedures; his skin became several shades paler, and his face underwent major reconstruction.

Over the course of more than a decade, Michael Jackson transformed from a handsome young man with typical African American features into a ghostly apparition of a human being. Some of the changes were casual and common, such as straightening his hair. Others were the product of sophisticated surgical and medical procedures; his skin became several shades paler, and his face underwent major reconstruction.

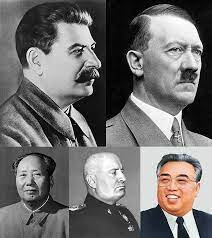

In this oft-reprinted quote from Hannah Arendt’s seminal work The Origins of Totalitarianism, many 21st century readers, particularly those engaged in pro-democracy movements in the United States and abroad, see Donald Trump and the emergent totalitarian formation of Trumpism sewn piecemeal onto the template that she constructed whole cloth from Hitler and Stalin’s political regimes. Although Trump hasn’t yet matched the political power, penchant for violence, or historical significance of Hitler or Stalin, he has made clear his disdain for democracy and exhibits a desire and willingness to use his power and violence to undo its institutional structures. For readers who are encouraged by the emergence of Trumpism and excited by its promise to make America great again, which includes inciting nationalistic pride, putting America’s interests first ahead of global concerns, policing public school curriculum for progressive ideological biases, packing the courts with sympathetic ideologues, and using banal procedural rules to derail the spirit of democratic negotiation and compromise then her work may provide you a cautionary tale regarding the potential implications of delivering on those promises.

In this oft-reprinted quote from Hannah Arendt’s seminal work The Origins of Totalitarianism, many 21st century readers, particularly those engaged in pro-democracy movements in the United States and abroad, see Donald Trump and the emergent totalitarian formation of Trumpism sewn piecemeal onto the template that she constructed whole cloth from Hitler and Stalin’s political regimes. Although Trump hasn’t yet matched the political power, penchant for violence, or historical significance of Hitler or Stalin, he has made clear his disdain for democracy and exhibits a desire and willingness to use his power and violence to undo its institutional structures. For readers who are encouraged by the emergence of Trumpism and excited by its promise to make America great again, which includes inciting nationalistic pride, putting America’s interests first ahead of global concerns, policing public school curriculum for progressive ideological biases, packing the courts with sympathetic ideologues, and using banal procedural rules to derail the spirit of democratic negotiation and compromise then her work may provide you a cautionary tale regarding the potential implications of delivering on those promises.

My name is Sarah Firisen, and I’m 5ft 2 inches tall and work in software sales. But I’m also, or used to be, Bianca Zanetti, a 5ft 9 size 0 (which I’m also not), fashion designer and proprietor of a chain of stores, Fashion by B. No, I’m not bipolar. Bianca Zanetti is my Second Life avatar.

My name is Sarah Firisen, and I’m 5ft 2 inches tall and work in software sales. But I’m also, or used to be, Bianca Zanetti, a 5ft 9 size 0 (which I’m also not), fashion designer and proprietor of a chain of stores, Fashion by B. No, I’m not bipolar. Bianca Zanetti is my Second Life avatar.

The Naxalite phase in Bengal was a short, tragic chapter in politics, but in Bengal’s cultural-emotional life its implications were deeper, and reflected in its literature (and films)—most poignantly yet forcefully captured by the writer Mahshweta Devi, one of Bengal’s most powerful political novelists. Again and again in the 20th century some of Bengali youth have been fascinated by the romanticism of revolutionary violence–as was the case in the early decades in the freedom struggle against the British (I have earlier mentioned about my maternal uncle caught in its vortex), then again in the 1940’s when the sharecroppers’ movement (called tebhaga) was soon followed by a period of communist insurgency in 1948-50, and then in the Naxalite movement of the late 60’s and early 70’s.

The Naxalite phase in Bengal was a short, tragic chapter in politics, but in Bengal’s cultural-emotional life its implications were deeper, and reflected in its literature (and films)—most poignantly yet forcefully captured by the writer Mahshweta Devi, one of Bengal’s most powerful political novelists. Again and again in the 20th century some of Bengali youth have been fascinated by the romanticism of revolutionary violence–as was the case in the early decades in the freedom struggle against the British (I have earlier mentioned about my maternal uncle caught in its vortex), then again in the 1940’s when the sharecroppers’ movement (called tebhaga) was soon followed by a period of communist insurgency in 1948-50, and then in the Naxalite movement of the late 60’s and early 70’s.

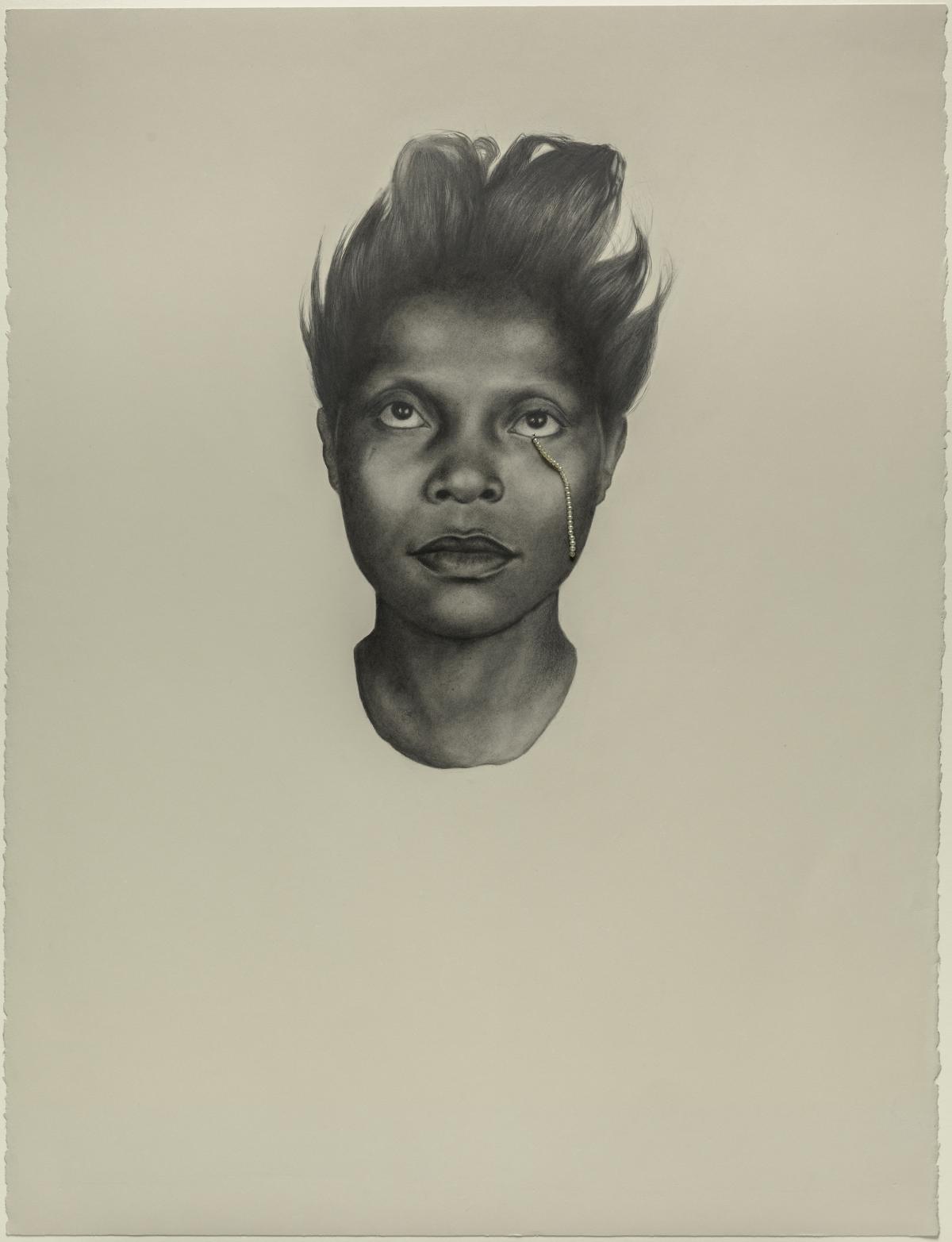

Whitfield Lovell. Kin XLV (Das Lied von der Erde), 2011.

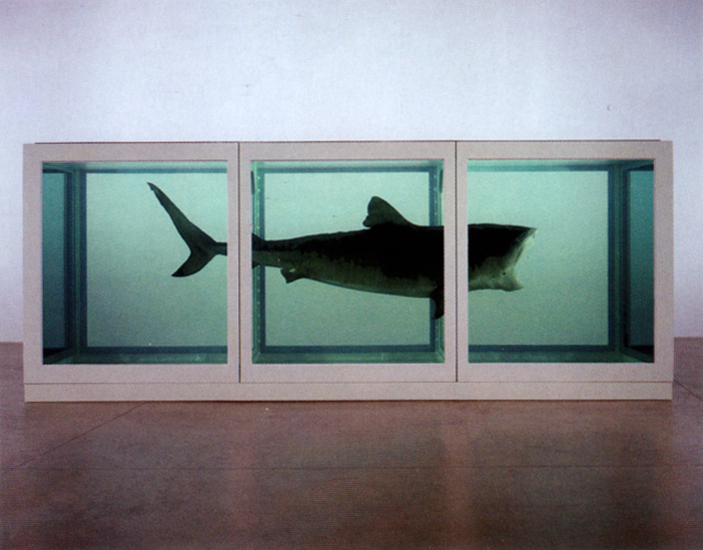

Whitfield Lovell. Kin XLV (Das Lied von der Erde), 2011. Not long ago, having steeled myself for the read-through of yet another dry but informative assessment of the body’s immune response to Covid 19 and her variant offspring, I was pleasantly surprised to find myself being dragged into a barbaric tale of murder and mayhem, full of gory details and dire strategies.

Not long ago, having steeled myself for the read-through of yet another dry but informative assessment of the body’s immune response to Covid 19 and her variant offspring, I was pleasantly surprised to find myself being dragged into a barbaric tale of murder and mayhem, full of gory details and dire strategies. We tell ourselves stories in order to live.

We tell ourselves stories in order to live.