by Ethan Seavey

I haven’t had a moment for words in weeks. I’ve been drowning myself in the minutia that sums into minutes. I take a nap. 30 second videos and 30 minute episodes on a screen my eyes strain to see. I spend half an hour making food and another eating it.

I feel the conflict within myself. I feel my body begging for satisfaction, for a good night’s rest and a home-cooked meal and a dozen eggs every three days and a good bowel movement. I treat the body like a puppy. I turn on Netflix and put my mind on autopilot: then bathe the body, cook for the body, bring the body to water, tuck the body into sleep. I treat it to plenty of walks and treats and it is happy.

But the mind suffers. It has to take care of the body and the person, Ethan, who needs to email this person and text that person. The brain must schedule this, and sign that. Plan and plan and plan for the future and block out the past and all the while the brain is itching for the phone.

The cure-all is scrolling. To watch more content online and be totally full of information and stimulus. The brain has no need to think for itself, to relieve the stresses causing my anxieties.

The soul, it’s the least important. It brings me security during the day to say I’m a writer and it relieves me at night to tell myself that I’m too tired to write today. The soul understands that I’m fighting a war here. The soul understands that it’s mostly a source of pain these days, and that to turn it off is easier. My soul’s really only satisfied as I sleep, as I dream of touching love’s skin and feeling safe, like I’ll never roll off the bed. Read more »

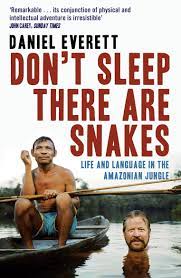

Daniel Everett’s 2008 book, Don’t Sleep, There are Snakes (Life and Language in the Amazonian Jungle), threw what seemed to be a pebble into the world of linguistics – but it is a pebble whose ripples have continued to expand. This might be thought surprising, in view of its curious construction. It contains a detailed description of the writer’s encounters with a small, remote Amazonian tribe, whom he calls the Pirahã (pronounced something like ‘Pidahañ’), but who apparently call themselves the Hi’aiti’ihi, roughly translated as “the straight ones.” They live beside the Maici River, a tributary of a tributary of the Amazon, which is nonetheless two hundred metres wide at its mouth.

Daniel Everett’s 2008 book, Don’t Sleep, There are Snakes (Life and Language in the Amazonian Jungle), threw what seemed to be a pebble into the world of linguistics – but it is a pebble whose ripples have continued to expand. This might be thought surprising, in view of its curious construction. It contains a detailed description of the writer’s encounters with a small, remote Amazonian tribe, whom he calls the Pirahã (pronounced something like ‘Pidahañ’), but who apparently call themselves the Hi’aiti’ihi, roughly translated as “the straight ones.” They live beside the Maici River, a tributary of a tributary of the Amazon, which is nonetheless two hundred metres wide at its mouth. Sometime before Ashok Rudra and I started on our large-scale data collection, I was already doing some theoretical and conceptual work on agrarian relations. My first, mainly theoretical, paper on share-cropping (jointly with TN) came out in American Economic Review in 1971. That paper was unsatisfactory and had quite a few loose strands, but it was one of the first papers to look theoretically into an economic-institutional arrangement of a developing country at the micro-level. This was a time when development economics was preoccupied with macro-issues like the structural transformation of the whole economy involving transition from agriculture to industrialization or problems of its aggregate interaction with more developed economies.

Sometime before Ashok Rudra and I started on our large-scale data collection, I was already doing some theoretical and conceptual work on agrarian relations. My first, mainly theoretical, paper on share-cropping (jointly with TN) came out in American Economic Review in 1971. That paper was unsatisfactory and had quite a few loose strands, but it was one of the first papers to look theoretically into an economic-institutional arrangement of a developing country at the micro-level. This was a time when development economics was preoccupied with macro-issues like the structural transformation of the whole economy involving transition from agriculture to industrialization or problems of its aggregate interaction with more developed economies. A provocative title, perhaps, and perhaps also counterintuitive. One thinks in the language one speaks, everybody knows that. Why would anyone ask bilingual speakers which language they think in (or dream in) otherwise?

A provocative title, perhaps, and perhaps also counterintuitive. One thinks in the language one speaks, everybody knows that. Why would anyone ask bilingual speakers which language they think in (or dream in) otherwise? The slim, green book Natural History of Western Massachusetts is one of my favorites. Compressed into its hundred odd pages are articles and visuals that describe the essential natural features of the Amherst region, where I’ve lived since 2008. I turn to it every time something outdoors piques my interest — a new tree, bird or mammal, a geological feature.

The slim, green book Natural History of Western Massachusetts is one of my favorites. Compressed into its hundred odd pages are articles and visuals that describe the essential natural features of the Amherst region, where I’ve lived since 2008. I turn to it every time something outdoors piques my interest — a new tree, bird or mammal, a geological feature. Everything in the universe that’s visible from your location on Earth passes by overhead every day. We’re usually able see only the stars, galaxies, planets, and so on that are in the sky when the sun is not; we become aware of them when the sun sets and Earth’s shadow rises from the eastern horizon. But all of them are there at some point in the day. We picnic beneath the winter constellation Orion in summer and walk beneath the Summer Triangle on the short days of winter. The moon also crosses the sky every day, sometimes in the daytime, and sometimes too close to the sun to be seen.

Everything in the universe that’s visible from your location on Earth passes by overhead every day. We’re usually able see only the stars, galaxies, planets, and so on that are in the sky when the sun is not; we become aware of them when the sun sets and Earth’s shadow rises from the eastern horizon. But all of them are there at some point in the day. We picnic beneath the winter constellation Orion in summer and walk beneath the Summer Triangle on the short days of winter. The moon also crosses the sky every day, sometimes in the daytime, and sometimes too close to the sun to be seen. I had my first panic attack at age sixteen, which was (deargod) over 35 years ago. It happened during school, much to my teenage mortification. Some friends and I were hanging out in our high school newspaper office during a free period, sprawled on one of the crapped-out couches under the blinking fluorescent lights, just shooting the shit. All of a sudden, a wave of horror swept over me—no, that’s not the right word. It was a feeling of fear mixed with a kind of existential dread, washing over me in waves, and then my heart was pounding, the walls were closing in, and I was gripped with an intense feeling of unreality. (This is something that people with panic disorder don’t often explain—or maybe it’s different for everyone. But for me the worst part of a panic attack is the

I had my first panic attack at age sixteen, which was (deargod) over 35 years ago. It happened during school, much to my teenage mortification. Some friends and I were hanging out in our high school newspaper office during a free period, sprawled on one of the crapped-out couches under the blinking fluorescent lights, just shooting the shit. All of a sudden, a wave of horror swept over me—no, that’s not the right word. It was a feeling of fear mixed with a kind of existential dread, washing over me in waves, and then my heart was pounding, the walls were closing in, and I was gripped with an intense feeling of unreality. (This is something that people with panic disorder don’t often explain—or maybe it’s different for everyone. But for me the worst part of a panic attack is the  Sughra Raza. Another Morning. Venice, July 2012.

Sughra Raza. Another Morning. Venice, July 2012. We primates of the

We primates of the