by Deanna K. Kreisel (Doctor Waffle Blog)

The other day my friend Matt told me a story about a camel that fell in love with him. Scott and I were on a Zoom call with him and his partner Tania—the two of us in Mississippi, Tania in Santa Barbara, and Matt in D.C. It had been a year since we’d all Zoomed (I remember this because both calls were on my birthday), and no one was sure how we’d let it go so long since we had so much fun whenever we talked. I had been friends with Matt and Tania in college when they were first dating, but we’d all fallen out of touch for decades. Although the phrase “first dating” is misleading: they were together for a year or so in college, broke up before graduating, went their separate ways (long relationships, a marriage, kids, doctorates, a divorce) and then got back in touch during the pandemic. And then started talking every day: Matt in dreary D.C. with his neutral greige therapist’s Zoom background, Tania in her sunny California kitchen with beautiful goblets of straw-colored wine and plates of imported cheese. And then they got back together again, over 30 years later. I hope there are lots more heartwarming Covid stories like this one out there, but this is the one I know about, and it’s a pretty fucking great one if I do say so myself.

So Matt and Tania were telling us that they were planning (ha ha! “planning”) to go on vacation together to Mexico in a few months, which prompted Matt to tell the story of the amorous camel, whom he had encountered on his last trip there. He was visiting a monkey sanctuary on the Mayan peninsula (as one does); there was a camel living there, too, who had previously been in a zoo or a circus, because the person running the sanctuary rescued all kinds of miscellaneous animals in his spare time. Matt and the camel immediately bonded the moment they met. I wish I had asked more questions at the time, because I now realize that I’m not 100% sure what “bonding with a camel” actually entails, but as Matt was telling the story it seemed to make perfect sense. They hung out together the whole time Matt was at the sanctuary, more than half an hour, basking in each other’s presence. I like to imagine that at one point Matt gently leaned against the camel’s flank, stroked his soft nose, and whispered something like “There there, big fella”—but of course I am making that up. As far as I can tell, Matt more or less ignored the monkeys, but we all have to make difficult choices from time to time. Read more »

Sughra Raza. Kaamdani, Approaching Santiago, Chile, 2017.

Sughra Raza. Kaamdani, Approaching Santiago, Chile, 2017.

In the game of chess, there are dramatic moves such as when a knight puts the king in check while at the same time attacking the queen from the same square. Such a move is called a fork, and it’s always a delicious feeling to watch your opponent purse his lips and shake his head when you manage a good fork. The most dramatic move is obviously checkmate, when you capture the king, hide your delight, and put the pieces back in the box. But getting to either the fork or checkmate involves what’s known in chess as positioning, and for the masters, often involves quiet moves long in advance of the victory.

In the game of chess, there are dramatic moves such as when a knight puts the king in check while at the same time attacking the queen from the same square. Such a move is called a fork, and it’s always a delicious feeling to watch your opponent purse his lips and shake his head when you manage a good fork. The most dramatic move is obviously checkmate, when you capture the king, hide your delight, and put the pieces back in the box. But getting to either the fork or checkmate involves what’s known in chess as positioning, and for the masters, often involves quiet moves long in advance of the victory.

From the gatherings at Ashis Nandy’s home, and particularly from my numerous discussions with him I learned to think a bit more carefully about three major social concerns in India.

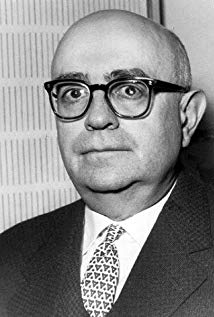

From the gatherings at Ashis Nandy’s home, and particularly from my numerous discussions with him I learned to think a bit more carefully about three major social concerns in India. The philosopher Theodore Adorno, probably with activities such as reading serious literature and listening to classical music in mind, famously said about himself:

The philosopher Theodore Adorno, probably with activities such as reading serious literature and listening to classical music in mind, famously said about himself:

Sughra Raza. Bey Unvaan. Anza-Borrego Desert Park, Calfornia, 2017.

Sughra Raza. Bey Unvaan. Anza-Borrego Desert Park, Calfornia, 2017.