by Charlie Huenemann

Lots of things don’t exist. Bigfoot, a planet between Uranus and Neptune, yummy gravel, plays written by Immanuel Kant, the pile of hiking shoes stacked on your head — so many things, all of them not existing. Maybe there are more things that don’t exist than we have names for. After all, there are more real objects than we have names for. No one has named every individual squid, nor every rock on Mars, nor every dream you’ve ever had. The list of existing things consists mostly of nameless objects, it seems.

Lots of things don’t exist. Bigfoot, a planet between Uranus and Neptune, yummy gravel, plays written by Immanuel Kant, the pile of hiking shoes stacked on your head — so many things, all of them not existing. Maybe there are more things that don’t exist than we have names for. After all, there are more real objects than we have names for. No one has named every individual squid, nor every rock on Mars, nor every dream you’ve ever had. The list of existing things consists mostly of nameless objects, it seems.

So there also must be a lot of nameless things that don’t exist. The collection of two marbles in my coffee mug — call it “Duo”. Duo doesn’t exist. Nor the collection of three marbles (“Trio”), nor the collection of four marbles, etc. Beyond Duo and Trio, there is an infinity of collections of marbles in my coffee cup that don’t exist, and the greatest portion of them, by a long shot, are nameless. Think of all the integers that don’t exist between 15 and 16. None of them have names. The world is full of them, or it would be, if they existed.

My guess is that there are more nameless things that don’t exist than there are nameless things that do exist. I have read that there is a finite number of particles that exist in the universe, and that’s probably going to limit the number of nameless existing things, somehow. But think of all the particles that don’t exist! There are far more of them, right?

How do we distinguish the nameless objects that do exist from the nameless objects that don’t exist? We could just say that the ones in the first group exist while the other ones don’t, and we would be right, but that doesn’t really explain how we tell the difference between the two. Read more »

A couple of weeks ago, the main healthcare provider in my city sent me a newsletter. One of the items was a brief blurb about how laughter is good for you, with a link to “Learn More About the Benefits of Laughter.” No! If you think laughter is good for our health, link to a video of a cat riding a Roomba or bear cubs on a hammock. I might click through to see those; I might even laugh. I’m not going to look at an article about the benefits of laughter, because it will become another open tab, a nagging chore, an obligation that stands between me and the conditions for laughter.

A couple of weeks ago, the main healthcare provider in my city sent me a newsletter. One of the items was a brief blurb about how laughter is good for you, with a link to “Learn More About the Benefits of Laughter.” No! If you think laughter is good for our health, link to a video of a cat riding a Roomba or bear cubs on a hammock. I might click through to see those; I might even laugh. I’m not going to look at an article about the benefits of laughter, because it will become another open tab, a nagging chore, an obligation that stands between me and the conditions for laughter. Sughra Raza. Mood … , Our Pale Blue Dot.

Sughra Raza. Mood … , Our Pale Blue Dot.

In both ISI and DSE there was one problem I faced in my research that was something I did not fully anticipate before. Some of the major international journals had a submission fee for research papers which was equivalent to something that would exhaust most of my Indian monthly salary. In the US authors mostly charged the fee to their research grants, which was not a way out for me. I once wrote about this to the Executive Committee of the American Economic Association (AEA), and suggested that for their journals they should have a lower rate for authors from low-income countries. I got a reply, saying that after careful consideration in their Committee meeting they had decided against my suggestion. Their rationale was a typical one for believers in perfect markets: since an article in an AEA journal was likely to raise significantly the expected lifetime earnings of an author, the latter should be able to finance it. (I visualized the dour face of an Indian public bank loan officer trying to comprehend this).

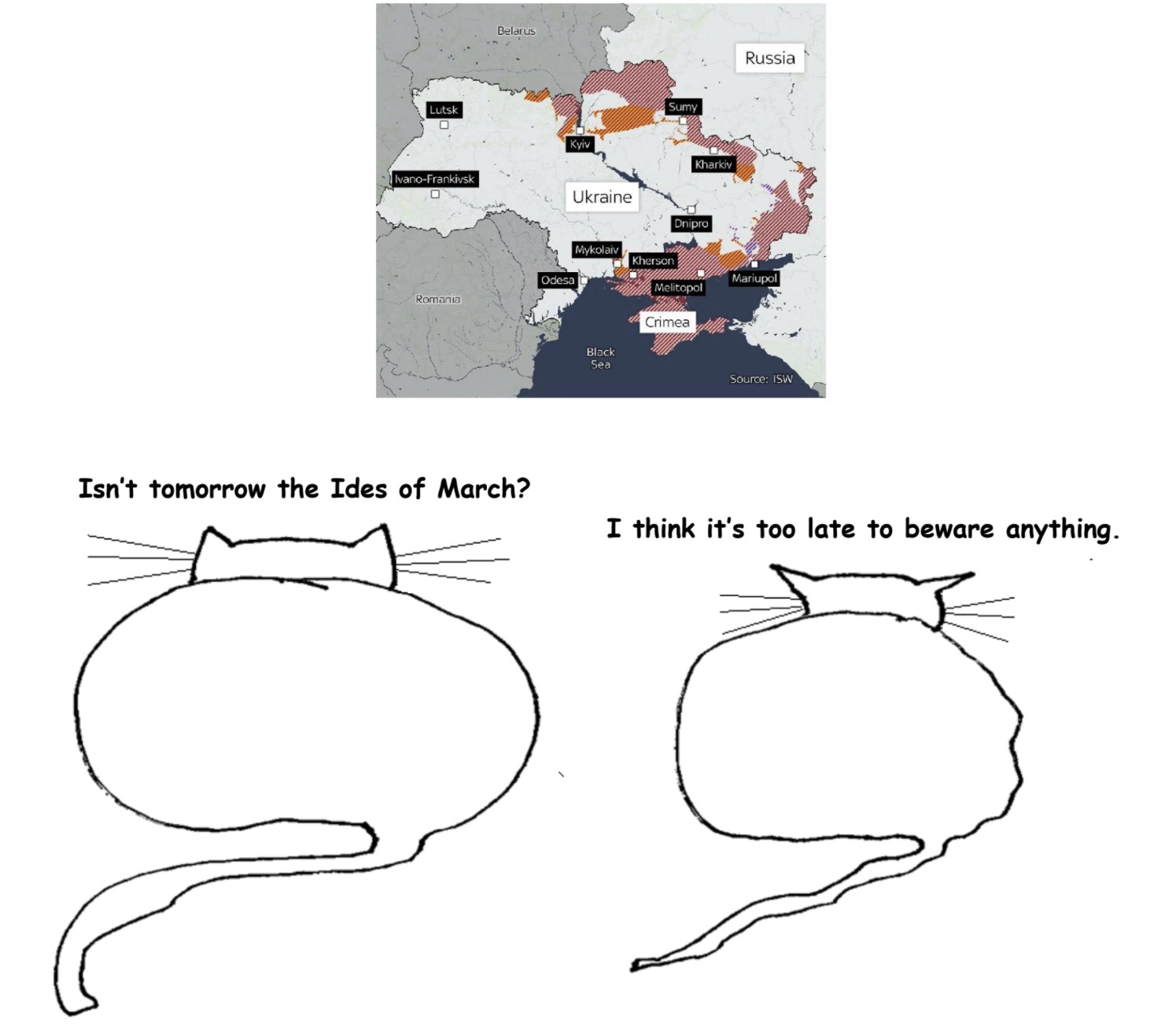

In both ISI and DSE there was one problem I faced in my research that was something I did not fully anticipate before. Some of the major international journals had a submission fee for research papers which was equivalent to something that would exhaust most of my Indian monthly salary. In the US authors mostly charged the fee to their research grants, which was not a way out for me. I once wrote about this to the Executive Committee of the American Economic Association (AEA), and suggested that for their journals they should have a lower rate for authors from low-income countries. I got a reply, saying that after careful consideration in their Committee meeting they had decided against my suggestion. Their rationale was a typical one for believers in perfect markets: since an article in an AEA journal was likely to raise significantly the expected lifetime earnings of an author, the latter should be able to finance it. (I visualized the dour face of an Indian public bank loan officer trying to comprehend this). Vladimir Putin’s decision to invade Ukraine is clearly a historically momentous event, already appearing to cause a seismic shift in the geopolitical landscape. What the long-term consequences will be are hard to say. The most obvious losers are the millions of Ukrainians–killed, injured, bereft, and displaced–who are the immediate victims of Putin’s onslaught. The most likely winner will probably be China, on whom Russia is suddenly much more economically dependent due to the sanctions imposed by the West, and who can therefore now expect Putin to dance to whatever tune it whistles.

Vladimir Putin’s decision to invade Ukraine is clearly a historically momentous event, already appearing to cause a seismic shift in the geopolitical landscape. What the long-term consequences will be are hard to say. The most obvious losers are the millions of Ukrainians–killed, injured, bereft, and displaced–who are the immediate victims of Putin’s onslaught. The most likely winner will probably be China, on whom Russia is suddenly much more economically dependent due to the sanctions imposed by the West, and who can therefore now expect Putin to dance to whatever tune it whistles. The Ouvroir de Littérature Potentielle (Workshop of Potential Literature), Oulipo for short, is the name of a group of primarily French writers, mathematicians, and academics that explores the use of mathematical and quasi-mathematical techniques in literature. Don’t let this description scare you. The results are often amusing, strange, and thought-provoking.

The Ouvroir de Littérature Potentielle (Workshop of Potential Literature), Oulipo for short, is the name of a group of primarily French writers, mathematicians, and academics that explores the use of mathematical and quasi-mathematical techniques in literature. Don’t let this description scare you. The results are often amusing, strange, and thought-provoking. Despite living here for nearly three years now, I have no social life to speak of. At risk of sounding self-loathing, a not insignificant part of the problem is probably just me: I’m not the most social person in the world. Plus, there’s the pandemic, which hit six months after we moved here. But I don’t think it’s just me, or even just the pandemic. An awful lot of people who moved here as adults, decades ago, and are much nicer and more sociable than I am, have said the same thing: making friends in Toronto is hard.

Despite living here for nearly three years now, I have no social life to speak of. At risk of sounding self-loathing, a not insignificant part of the problem is probably just me: I’m not the most social person in the world. Plus, there’s the pandemic, which hit six months after we moved here. But I don’t think it’s just me, or even just the pandemic. An awful lot of people who moved here as adults, decades ago, and are much nicer and more sociable than I am, have said the same thing: making friends in Toronto is hard.