by Michael Abraham

I am leaving, and I am taking nothing.

I am leaving, and I am taking nothing.

I am leaving, and I am taking nothing, and there is a void inside me—a round, black sphere, like a planet, or like the absence of a planet where a planet should be. I am coming apart in the stress of it. I am borrowing money and time, bleeding my pride out my feet as I run from this bar to that bar to be anywhere, to be out. It is not only that I am sad. It is that I am depleted, that I have given all I can give, and, now, there is no gift left. There is no gift, as in, there is no special sense of possibility glimmering, of the impossible becoming possible through me. There was once this gift, this special sense, and now there is only its having been there, its having flown off to someone somewhere else.

***

I walk circles around this place that I am leaving, and I note all the little, special things, the daily clutter of being alive. I do not think about the time that I have spent here. I think only of leaving, of fluttering off like a moth—not like a butterfly, for I am not going off in a gay manner. I am somber like a moth. To be somber is not to be destitute; it is not to despair. There is a certain resignedness to being somber, a certain goodnaturedness. One who is somber is like falling water, carried forward irrepressibly, tinkling and shimmering as the onward pull of gravity does what it will always do, which is to draw on and downward—that is to say, to be somber is to face inevitability. One who is somber has an air about him, is better-off than other sad folks. One who is somber is like a moth. This is the best that I can explain it, the allure of the feeling that I am feeling. It is not enough to say that everything in my life is ending and starting again. That is true. But it is better to say that I am a small and fragile thing, a small and fragile thing with a certain gravitas, a certain solemnity, moving into the broader world to see what the broader world has in store, moving into the broader world because there is no choice, because it is in my nature to move. Fluttering, fluttering.

***

I don’t want to get into specifics because specifics muddy the water; they make complication where there might be the simplicity of feeling and all its affordances. Read more »

In Barcelona the daily scramble to deliver children to school results in terrible congestion in the upper part of the city, where the more economically privileged send their children. Watching this phenomenon brings back my own school days, when the most embarrassing thing any of us could imagine was being dropped off by parents. If such a thing were necessary for some unavoidable reason, the kids urged their parents to drop them a short distance away from the school so their peers wouldn’t see them getting out of the car. To be seen being coddled in this way was unimaginably embarrassing, almost as bad as having your mother show up to deliver a forgotten lunch box. Everything about parents tended to be embarrassing and much of the time we pretended not to have any. But there was a single exception to the drop-off rule. If the parents happened to own a 1956 Chevrolet, with its futuristic swept-wing design, then it was obligatory to be dropped off at school on some occasion, even if the ride was for only for a couple of blocks, so the other kids could look with sheer envy on this most prestigious possession.

In Barcelona the daily scramble to deliver children to school results in terrible congestion in the upper part of the city, where the more economically privileged send their children. Watching this phenomenon brings back my own school days, when the most embarrassing thing any of us could imagine was being dropped off by parents. If such a thing were necessary for some unavoidable reason, the kids urged their parents to drop them a short distance away from the school so their peers wouldn’t see them getting out of the car. To be seen being coddled in this way was unimaginably embarrassing, almost as bad as having your mother show up to deliver a forgotten lunch box. Everything about parents tended to be embarrassing and much of the time we pretended not to have any. But there was a single exception to the drop-off rule. If the parents happened to own a 1956 Chevrolet, with its futuristic swept-wing design, then it was obligatory to be dropped off at school on some occasion, even if the ride was for only for a couple of blocks, so the other kids could look with sheer envy on this most prestigious possession.  Since my Chair was in International Trade, most of my teaching in Berkeley was in that field of Economics, both at the graduate and undergraduate levels. The undergraduate classes in Berkeley are large, and mine had sometimes more than 200 students, even though this course was meant mostly for later-year undergraduates. Large classes bring you in close touch (particularly in office hours) with a refreshing diversity of young people. But they also bring other kinds of experience.

Since my Chair was in International Trade, most of my teaching in Berkeley was in that field of Economics, both at the graduate and undergraduate levels. The undergraduate classes in Berkeley are large, and mine had sometimes more than 200 students, even though this course was meant mostly for later-year undergraduates. Large classes bring you in close touch (particularly in office hours) with a refreshing diversity of young people. But they also bring other kinds of experience. At least Ben was polite about it. The rest of Judge Jackson’s hearing was absolutely awful. If you watched or read or otherwise dared approach the seething caldron of toxicity created by the law firm of Cotton, Cruz, Graham & Hawley (no fee unless a Democrat is smeared) you’ve probably had more than enough, so I’ll try to be brief before getting to more substantive matters.

At least Ben was polite about it. The rest of Judge Jackson’s hearing was absolutely awful. If you watched or read or otherwise dared approach the seething caldron of toxicity created by the law firm of Cotton, Cruz, Graham & Hawley (no fee unless a Democrat is smeared) you’ve probably had more than enough, so I’ll try to be brief before getting to more substantive matters.

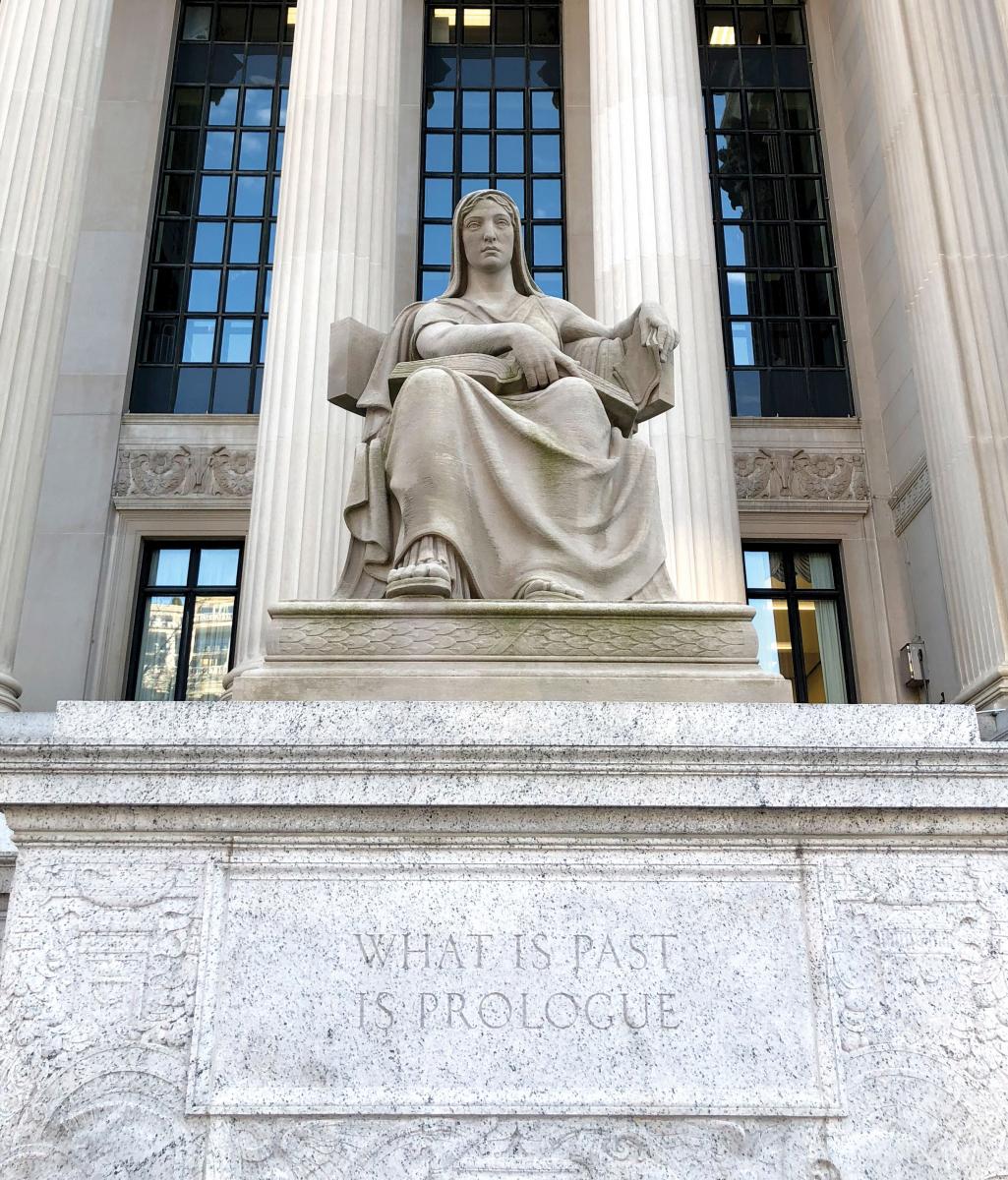

Is the Past Prolog? I’m not convinced. I say this as a professional historian.

Is the Past Prolog? I’m not convinced. I say this as a professional historian. He had a visceral aversion to war, was strongly in favor of social distancing in times of pandemic, and believed it would be a good thing if the Germans turned down their heaters a notch or two.

He had a visceral aversion to war, was strongly in favor of social distancing in times of pandemic, and believed it would be a good thing if the Germans turned down their heaters a notch or two.

Anticipating war in Europe, 2022.

Anticipating war in Europe, 2022. Over the last few weeks, I’ve been spending more time in the office than I have since the start of COVID. I work for a technology start-up, and our New York office used to look and feel just as shows like Silicon Valley portrayed such offices: cool furniture, fancy coffee machines, lots of free snacks, gaming systems and board games piled up in a dedicated room, and lots of young people who gave the office a fun, high energy, even if noisy, vibe. But this visit, while the snacks and coffee machines are still there, the office has a rather ghost town-like feel. There’s been no mandate to return to the office, so for the most part, people haven’t. Every day I saw my colleague Andy who lives in a Manhattan apartment that’s too crowded with family and a dog. He escapes to the office for some peace of quiet. Then there was the receptionist and the facilities manager, who had no choice but to be there. But that was it for regulars. The odd person would float in for a bit, have a meeting, then leave. Is this the future of office life?

Over the last few weeks, I’ve been spending more time in the office than I have since the start of COVID. I work for a technology start-up, and our New York office used to look and feel just as shows like Silicon Valley portrayed such offices: cool furniture, fancy coffee machines, lots of free snacks, gaming systems and board games piled up in a dedicated room, and lots of young people who gave the office a fun, high energy, even if noisy, vibe. But this visit, while the snacks and coffee machines are still there, the office has a rather ghost town-like feel. There’s been no mandate to return to the office, so for the most part, people haven’t. Every day I saw my colleague Andy who lives in a Manhattan apartment that’s too crowded with family and a dog. He escapes to the office for some peace of quiet. Then there was the receptionist and the facilities manager, who had no choice but to be there. But that was it for regulars. The odd person would float in for a bit, have a meeting, then leave. Is this the future of office life?