by Thomas O’Dwyer

At one point midway on our path in life,

I came around and found myself searching through a dark wood, the right way blurred and lost.

How hard it is to say what that wood was, a wilderness savage, brute, harsh, and wild.

Only to think of it renews my fear.

The opening lines of Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy are as well know to every Italian as “To be or not to be” is to an English speaker. We can only speculate on how many people outside Italy are familiar with the entire poem’s content or context. But none can dispute the depth to which Dante, like Shakespeare, has penetrated not only his native culture but that of the world for centuries. Both did civilisation an immeasurable service by elevating former dialects spoken by their native peoples to the same dignity and power as formal “superior” languages spoken by Europe’s literate elites, such as Latin and Greek.

Dante died 700 years ago this year in 1321 and, pandemic or no pandemic (a dark wood, the right way blurred and lost), Italy will again be celebrating the memory of its great genius. He defines its national soul the same way Shakespeare does for England and Miguel de Cervantes for Spain. Events are planned throughout Florence, Ravenna and close to 100 other towns and villages connected to “il Sommo Poeta,” the Supreme Poet. Born in Florence, Dante died in Ravenna just one year after completing his masterpiece. The Divine Comedy, one of the greatest works of world literature, has 14,233 lines split into three parts, Inferno, Purgatorio and Paradiso. It traces a pilgrim’s journey in the afterlife through Hell, Purgatory and Paradise.

The pilgrim is Dante, a 35-year-old persona of the author he weaves into the poem’s rich tapestry. After entering the dark wood on the night before Good Friday, 1300, Dante is threatened by a leopard, a lion and a she-wolf, before the ghost of the great poet Virgil comes to the rescue. But it is a rescue mission that will take them to the depths of Hell, just like Virgil, as an author, once guided Aeneas to the underworld of the ancients. At the entrance to Hell, Dante passes through the portal inscribed with its chilling warning: “Lasciate ogne speranza, voi ch’entrate” — Abandon all hope, you who enter here.” After the descent through mounting pain, blood and horror in flames and ice, they finally exit at Mount Purgatory’s foot and climb its nine terraces. At the summit of Purgatory, Virgil fades away and Beatrice takes over as Dante’s guide through the nine circles of Paradise.

By choosing to write in Tuscan rather than Latin, Dante established this dialect as standard Italian, so he is regarded as the father of the lovely modern language. The poem’s theme is the state of souls after death and the divine justice handed out as appropriate punishments for sins or evil deeds or as rewards for lives honestly or lovingly lived. Despite being based on the established medieval Catholic world-view, the poem towers far above glib piety or defunct theology. Today, it is still beautiful poetry and a monumental examination of human aspirations, follies, and downright evil. Dante’s cast of characters remains recognisable today as people who can love, hope, build and forgive with the same passion they also use to torture, hate, destroy and exterminate.

The subversive influence this 700-year old medieval epic continues to wield is astonishing — even if indirectly through the thousands of other writers, artists and musicians who have drawn on it for inspiration. The blood, gore and tortures of the Inferno have always made it the most popular of the three books. It highlights our morbid fascination with such evils as well as our appetite for seeing evildoers and enemies, especially the rich, powerful and hypocritical ones, get their everlasting comeuppance. Also, good is dull, so Paradiso is the least read of the Comedy, which is a shame because it’s poetry is superb. Victor Hugo commented on the Paradiso: “The human eye was not made to look upon so much light, and when the poem becomes happy, it becomes boring.”

Inferno is never boring. Dante had a special place in his Hell for corrupt ecclesiastics who had grown rich selling religious privileges like pardons or indulgences — the sin of simony. Where they had once baptised Christian babies by dipping their heads in water to symbolically cleanse the soul, in Hell they were buried head down in narrow pits with only their feet showing:

The soles of all these feet were set alight, and each pair wriggled at the joint so hard they’d easily have ripped a rope or lanyard.

As flames go flickering round some greasy thing and hover just above its outer rind, so these flames also, toe tip to heel end.

Talk about holding a miscreant’s feet to the fire — it’s hard to read that without instinctively twitching toes.

The horrors of the Inferno that Dante designed are still culturally with us. In 2010 the video games giant Electronic Arts released Dante’s Inferno computer game in a blaze of marketing hype. The game transforms Dante from a poet to a Crusader. (This is not too flagrant a liberty since the real 24-year-old Dante fought in the 1289 Battle of Campaldino with a pro-papal army against a faction supporting the Holy Roman Emperor.) Dante has fought and beaten Death in the game and returns home armed with the grim reaper’s scythe. His villa in Tuscany is in ruins, and his beloved Beatrice lies dead in the garden. Her ghost (having acquired giant breasts, of course) gives Dante his mission — rescue her from Hell. In Dante’s poem, Beatrice dies young, but looking down from heaven, she sees Dante’s soul is in danger and sends help to guide him through the dark wood to salvation.

In the game and typical of the genre, Dante must fight nasty enemies as he descends the terraced funnel of Hell to reach Beatrice. The graphics become more eerie, grim, and gory, indicating at least that the game makers were familiar with the original. It gives one pause to ponder the long reach of Dante’s imagination across 700 years to engage the minds of young digital warriors even he could never have conceived. I’m not sure he would have approved of the game’s profiteering in which players can buy relics and new powers in Hell, paying for them with the souls of those they have killed — simony in reverse, perhaps.

The Divine Comedy is still read or referenced and quoted by writers and other artists for many reasons. It is a text that lends itself to new, newer and renewed readings. A quality that has resonated down the centuries and connects Dante with modern readers is his eternal human empathy. He can be briefly vengeful against the worst criminals and enemies he encounters but never hardens his heart to the sufferers around him. Hell is a strange and infinite bureaucracy where the sinners face punishments that mirror their crimes, but Dante never fails to show compassion.

“One reason for Dante’s enduring power is that we have not really left the middle ages,” Guardian critic Jonathan Jones wrote in an essay on the Comedy. “Vendetta still rules. Entire foreign policies, not to mention civil wars and terror campaigns, are based on ideas of revenge and polarities of good and evil just as primitive as anything in Dante. The great Italian challenges us because he proposes a morally absolute vision of life that cuts through modern relativism like a knight’s broadsword. So the world is ambiguous, and our actions impossible to morally judge? Dante menaces us with an alternative possibility — every act is scrutinised, every moment of our lives is weighed in the balance.”

Over the past year, several essayists and columnists have drawn on the Divine Comedy for reference or comfort — 2020 was our year in the dark wood, menaced by the she-wolf of a pandemic, the lion of Trumpism and the leopard of climate change. Any possible paradise is far off on the other side of who knows what hells and purgatories.

Literature professor Filippo Gianferrari, of California University at Santa Cruz, penned an essay titled A Dantean reflection on the ecological disaster of isolation:

“I see in our current condition a fitting Dantean contrapasso, a retribution for the social isolation that had plagued our society long before this pandemic … We have raced to develop unprecedented means of communication that allow us to speak with, and hear, only those we choose: they have turned into antidotes against others’ coercion of us. Now we desperately search them for a hint of humanity, a hint of that unchosen connection, the fortuitous demands of strangers who ought to be neighbours. As a punishment for our social apathy, we have been deprived of all society.”

Partly responsible for the enduring fame and relevance of the Divine Comedy has been the attention artists pay to it. In 1495 Sandro Botticelli painted a famous portrait of Dante and many themes from the Comedy. Italy begins this year of Dante anniversary events with a virtual exhibition from the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. The drawings, by the 16th-century Renaissance artist Federico Zuccari, are being exhibited online. Only a few scholars have seen them, and they were displayed to the public only twice, and only partially. The first time was in Florence in 1865 to mark the 600th anniversary of Dante’s birth. The second was for an exhibition in Abruzzo in 1993.

Zuccari completed the sketches during a stay in Spain in 1586–1588. Of the 88 pieces, 28 depict Hell, 49 Purgatory and 11 Heaven. After Zuccari died in 1609, the Orsini family, for whom the artist had worked, held the drawings. They passed to the Medici family before becoming part of the Uffizi collection in 1738. In modern times, Robert Rauschenberg did an unusually provocative Dante cycle that included collaged riots and riot police images in 1960s America. How recurringly topical is Dante! The most haunting of all illustrations for the Divine Comedy are those created by Gustave Doré in 19th-century France.

On the topic of contemporary relevance, Dante has not escaped the attentions of political correctors. Eight years ago, a leading Italian human-rights organisation fired off a broadside against the country’s greatest poet and his masterwork. Gherush92, which advises the UN on human rights, demanded that the Divine Comedy be removed from school curriculums because it is “offensive and discriminatory” and young people lacked “the filters” to understand it. Abandon hope, all you who enter without trigger warnings. “In the Divine Comedy there is racist, Islamophobic and antisemitic content,” said Valentina Sereni, president of Gherush92. “Art cannot be above criticism.” Among the offensive allusions, she cited Judas, being eternally chewed in Lucifer’s teeth; Mohammed depicted as “torn from the chin down to the part that gives out the foulest sound”, and homosexuals under a rain of fire in purgatory. The poem, therefore, slanders Jews, says Islam is heresy and is homophobic.

It was not a campaign that stuck — one columnist suggested there was “a special place in Dante’s Hell” for those who attempted to bowdlerise universal works of art. Author and critic Giulio Ferroni scoffed at “another frenzy of political correctness, combined with historical ignorance.” He said: “Add a few more footnotes, fine. But abandon the study of a masterpiece that has helped build the image of humanity? What folly!”

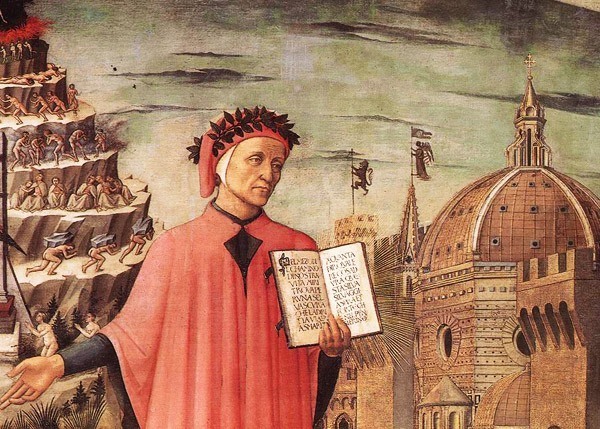

When author Dan Brown published the novel Inferno in his Robert Langdon thriller series in 2013, travel writers noted that Florence city officials were delighted by this “gift of tourism” from Brown to Dante and the artists who illustrated him. One such painting drawing bigger crowds because of Brown’s Inferno was the 1465 work by Domenico di Michelino in Florence cathedral. In the picture, Dante stands as a colossus in a red robe presenting the Divine Comedy to Florence city, which he towers over.

An over-enthusiastic Guardian reviewer urged his readers: “Give yourself a treat this summer. Read Dan Brown’s Inferno; why not. But also read a translation of the Divine Comedy illustrated with Botticelli’s wonderful drawings.” At least one Guardian reader was not impressed. In the comments section the person wrote:

“Unfortunately you’ve been condemned to spend eternity reading the collected works of Dan Brown. Please make your own way to the Dan Brown Circle — it’s a couple of circles down from the lake of shit. You’ve been allocated a personal imp, who will dangle copies of the Divine Comedy just out of your reach forever.”