by Jeroen Bouterse

“The constant direct mode of address was a chore. No one will enjoy having this read to them.” Quoting from a referee report on the Nicomachean Ethics misses the point of James Warren’s hilarious rejection letter, but I looked it up because I remember thinking that the fictional critic was onto something, and not just about Aristotle. “I had the impression at times that some kind of conversational or dialectical background was being assumed but this is not at all marked in the text.” Indeed! Why hide the fun part?

“The constant direct mode of address was a chore. No one will enjoy having this read to them.” Quoting from a referee report on the Nicomachean Ethics misses the point of James Warren’s hilarious rejection letter, but I looked it up because I remember thinking that the fictional critic was onto something, and not just about Aristotle. “I had the impression at times that some kind of conversational or dialectical background was being assumed but this is not at all marked in the text.” Indeed! Why hide the fun part?

I owe several very happy moments to well-executed philosophical dialogues: Imre Lakatos’ Proofs and Refutations, Larry Laudan’s Science and Relativism, and Aristotle’s former supervisor come to mind. I will be ever so grateful to anybody who can point me to similarly exciting conversations. The dialogue form draws and holds the attention: it can let worldviews clash in the abstract, but it can simultaneously delve into matters of detail without becoming boring – these details having been established, after all, to flow not just from the idiosyncratic preoccupations of one contingent mind, but from larger intellectual interests common to at least two separate perspectives.

Still, they are usually written by one person. I was thrilled last year to find out about a philosophical dialogue where both positions were written by people actually holding them: in Just Deserts (2021), Gregg Caruso and Daniel Dennett debate the implications of their ideas about free will, especially via the question whether people ‘deserve’ blame, praise, punishment and reward (henceforth ‘BPPR’) for their actions. Caruso’s position is that there is an important sense in which they don’t, and that this ought to be reflected in the way in which we deal with bad or criminal behavior. Read more »

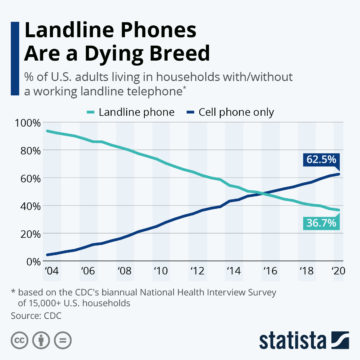

Lanchester’s square law was formulated during World War I and has been taught in the military ever since. It is marginally relevant to the war in Ukraine, particularly the balance between the quantity and quality of the two armies’ weapon systems.

Lanchester’s square law was formulated during World War I and has been taught in the military ever since. It is marginally relevant to the war in Ukraine, particularly the balance between the quantity and quality of the two armies’ weapon systems.

I regret not having children younger. Like, much younger. I was thirty-six when my first child, now four, was born; thirty-eight when my second was born. I wish I had done it when I was in my early twenties. This is an unpopular perspective. I know this because when I’ve raised this feeling with friends, many of whom had children similarly late in life, I’ve been met with a strong resistance. It’s not just that they don’t share my feelings, that their experience of having children later in life is different to mine, it’s that they somehow mind me feeling the way that I do. They think that I am wrong – mistaken – to feel this way. It upsets them.

I regret not having children younger. Like, much younger. I was thirty-six when my first child, now four, was born; thirty-eight when my second was born. I wish I had done it when I was in my early twenties. This is an unpopular perspective. I know this because when I’ve raised this feeling with friends, many of whom had children similarly late in life, I’ve been met with a strong resistance. It’s not just that they don’t share my feelings, that their experience of having children later in life is different to mine, it’s that they somehow mind me feeling the way that I do. They think that I am wrong – mistaken – to feel this way. It upsets them.  The dandelion is thousands of miles from home. It has been in America learning about the world beyond and perhaps it wants to return. It has lived thousands of sad lives. Finally after 300 years, a seed clings to an old man’s jacket as he boards a plane, and happens to land in a small patch of dirt right by the Charles de Gaulle airport; the dandelion is welcomed home graciously, and they share the stories of what has happened in its absence. They notice little differences to him. He has mutated slightly; the increased sun in America has made his petals more yellow; the lawn mowers have made him shorter; the pesticides have made him stronger. They don’t talk to him about the sun or the lawn mowers or the pesticides, though. They talk about their shared home in France.

The dandelion is thousands of miles from home. It has been in America learning about the world beyond and perhaps it wants to return. It has lived thousands of sad lives. Finally after 300 years, a seed clings to an old man’s jacket as he boards a plane, and happens to land in a small patch of dirt right by the Charles de Gaulle airport; the dandelion is welcomed home graciously, and they share the stories of what has happened in its absence. They notice little differences to him. He has mutated slightly; the increased sun in America has made his petals more yellow; the lawn mowers have made him shorter; the pesticides have made him stronger. They don’t talk to him about the sun or the lawn mowers or the pesticides, though. They talk about their shared home in France.

Halfway through a pilgrimage, it’s a good thing to remember why you’re on it – where you hope it’s taking you. I’m following a plan to consider the strangely numerous churches of this little Portland neighborhood, just a half-mile square but crowded with varieties of religiosity.

Halfway through a pilgrimage, it’s a good thing to remember why you’re on it – where you hope it’s taking you. I’m following a plan to consider the strangely numerous churches of this little Portland neighborhood, just a half-mile square but crowded with varieties of religiosity.