by Allen Hornblum

Fifty years ago this July, newspaper headlines shocked the conscience of the nation with a disturbing story of racial bias and medical mistreatment in one of America’s most honored institutions. The alarming Associated Press story first appeared on July 25, 1972 in the Washington Star. The front page headline, “Syphilis Patients Died Untreated,” caught readers attention. They’d go on to read that the goal of a strange, non-therapeutic experiment conducted by the United States Public Health Service (USPHS) was not to treat the sick or save lives, but “determine from autopsies what the disease does to the human body.”

Fifty years ago this July, newspaper headlines shocked the conscience of the nation with a disturbing story of racial bias and medical mistreatment in one of America’s most honored institutions. The alarming Associated Press story first appeared on July 25, 1972 in the Washington Star. The front page headline, “Syphilis Patients Died Untreated,” caught readers attention. They’d go on to read that the goal of a strange, non-therapeutic experiment conducted by the United States Public Health Service (USPHS) was not to treat the sick or save lives, but “determine from autopsies what the disease does to the human body.”

The next day every newspaper in the country covered the story. The New York Times front-page headline “Syphilis Victims in U.S. Study Went Untreated For 40 Years,” informed readers that hundreds of illiterate Black sharecroppers with syphilis in Alabama were denied treatment due to their participation in a scientific study. The alarming revelation not only provoked outrage and embarrassment, but caused Americans to look with a more discerning eye at what was occurring in the hospitals, orphanages, and prisons in their communities. It would also spark a long-overdue re-evaluation of the medical community’s cavalier practice of using vulnerable populations as raw material for experimentation.

How could such a thing happen in America people wanted to know, especially under the auspices of the government and scientific community? In the following days and months, academics, lawmakers, ethicists, and op-ed writers would ponder what the repugnant, four-decade long study of “Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male” said about science, race, and the soul of America? Now, a half-century on and over two decades into the 21st century – and the 90th anniversary of the infamous Tuskegee Syphilis Study’s inception – we are still reflecting on those same questions. Read more »

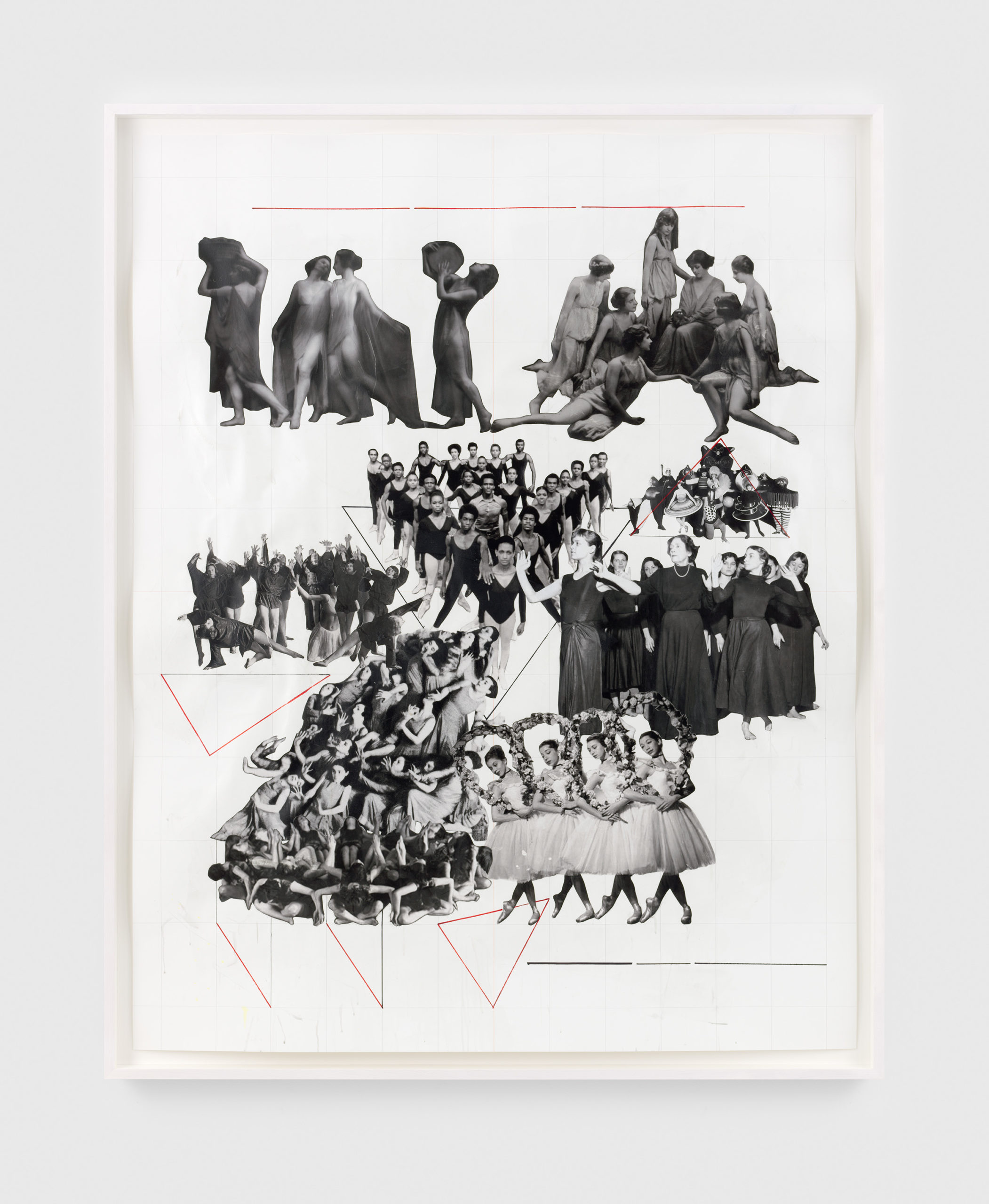

Kandis Williams. Triadic Ensemble: stacked erasures, 2021.

Kandis Williams. Triadic Ensemble: stacked erasures, 2021.

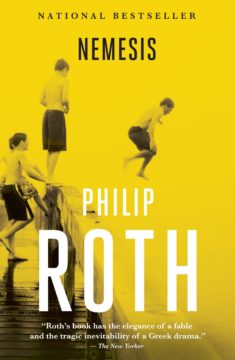

I recently read Philip Roth’s Nemesis, a novel that’s received renewed attention as it centers on a polio epidemic. This isn’t why I read it, although I’ll admit that reading about the slow build and then cascading avalanche of a virus, and the public’s nonchalance giving way to caution and then increased panic and hysteria, closely paralleled the events of early 2020. I suppose epidemics and our response to them always play out in a similar fashion. I picked the book off my shelf because I needed something to read—much like the setting of the novel, it’s summer vacation for me. My dad had given me the book some time before, and it had sat there, collecting dust on the shelf built into the low walls of my slope-ceilinged attic apartment. As a rule, I hate receiving books as gifts because I then feel an obligation to read them; instead, I prefer to choose and read a book in a more serendipitous fashion. It’s not something that can be forced. But if the giver of the book knows that their gift will go unread, possibly for years, but will then present itself to be read at the right moment, a book can be a great gift.

I recently read Philip Roth’s Nemesis, a novel that’s received renewed attention as it centers on a polio epidemic. This isn’t why I read it, although I’ll admit that reading about the slow build and then cascading avalanche of a virus, and the public’s nonchalance giving way to caution and then increased panic and hysteria, closely paralleled the events of early 2020. I suppose epidemics and our response to them always play out in a similar fashion. I picked the book off my shelf because I needed something to read—much like the setting of the novel, it’s summer vacation for me. My dad had given me the book some time before, and it had sat there, collecting dust on the shelf built into the low walls of my slope-ceilinged attic apartment. As a rule, I hate receiving books as gifts because I then feel an obligation to read them; instead, I prefer to choose and read a book in a more serendipitous fashion. It’s not something that can be forced. But if the giver of the book knows that their gift will go unread, possibly for years, but will then present itself to be read at the right moment, a book can be a great gift. By the time I got to high school, the humanities were seen as a kind of side dish in the educational meal. This was largely due to the exigencies of the space race and an inclination on the part of American society to acquiesce to the suppression of critical thought in the post-war years. The main course from a geopolitical perspective was science and engineering.

By the time I got to high school, the humanities were seen as a kind of side dish in the educational meal. This was largely due to the exigencies of the space race and an inclination on the part of American society to acquiesce to the suppression of critical thought in the post-war years. The main course from a geopolitical perspective was science and engineering.

Guns guns guns

Guns guns guns  Since 1990 I have also visited Vietnam a few times. Vietnamese economic reform (called doi moi) started in the mid-1980’s. On my first visit I found Hanoi to be more like a small quiet town in India, with a lot of poverty (and some begging in the streets, but not many visibly malnourished children), while Saigon or Ho Chi Minh City was somewhat better-off, and more raucous and colorful. One lecture I gave in Vietnam was titled “ The Rocky Road to Reform” where I spelled out the challenges of economic transition from a state-dominated economy; after my lecture a Vietnamese academic came to me and said, “Our roads are all full of potholes, so we are used to the ‘rocky road’ of challenges”!

Since 1990 I have also visited Vietnam a few times. Vietnamese economic reform (called doi moi) started in the mid-1980’s. On my first visit I found Hanoi to be more like a small quiet town in India, with a lot of poverty (and some begging in the streets, but not many visibly malnourished children), while Saigon or Ho Chi Minh City was somewhat better-off, and more raucous and colorful. One lecture I gave in Vietnam was titled “ The Rocky Road to Reform” where I spelled out the challenges of economic transition from a state-dominated economy; after my lecture a Vietnamese academic came to me and said, “Our roads are all full of potholes, so we are used to the ‘rocky road’ of challenges”!

Sughra Raza. Shadows on Beech Trunk, May 21, 2022.

Sughra Raza. Shadows on Beech Trunk, May 21, 2022. Not

Not

“The constant direct mode of address was a chore. No one will enjoy having this read to them.” Quoting from a referee report on the Nicomachean Ethics misses the point of James Warren’s hilarious

“The constant direct mode of address was a chore. No one will enjoy having this read to them.” Quoting from a referee report on the Nicomachean Ethics misses the point of James Warren’s hilarious