by Tim Sommers

Computers are not alive. Hopefully, we can agree on that. It’s a place to start.

But if anyone succeeds at creating a program that exhibits true artificial general intelligence, wouldn’t such a program, despite not being alive in the biological sense, deserve some kind of moral consideration? Or, at least, if we loaded the AI into a robot body, especially one capable of experiencing pain-like discomfort, wouldn’t it be wrong to use it as a slave? (Ironically, the word “robot” comes from a 1921 Czech play, R.U.R. (“Rossum’s Universal Robots”) by Karel Čapek, and specifically from “robata,” which is just the Czech word for “slave.”)

But if an AI exhibited certain characteristics, like human-level intelligence, we would consider it, I hope, a person in the moral sense, despite its not being alive. On the other hand, presumably streptococcus or human sperm, while clearly alive are not persons. If that’s right, then being alive, in the biological sense, is neither necessary nor sufficient for being a person in the moral sense.

If friendly, intelligent aliens showed up to help us out with global warming, they would probably be alive, unless they were robots. And they would, of course, not be human (unless they seeded the Earth long ago with their DNA and they are us). But if they are intelligent, able to communicate, and act with admirable intentions, they would deserve to be treated as “persons” in the moral sense, surely? Similarly, if we succeed at decoding dolphin language, or find that some other nonhuman animal exhibits intelligence on par with human intelligence, shouldn’t we think of them as persons? Non-human persons, sure, but persons nonetheless.

Since whether you are human or alive does not settle the question of your personhood, we are going to need some other criteria. But, first, what do we mean by personhood in the moral sense? Read more »

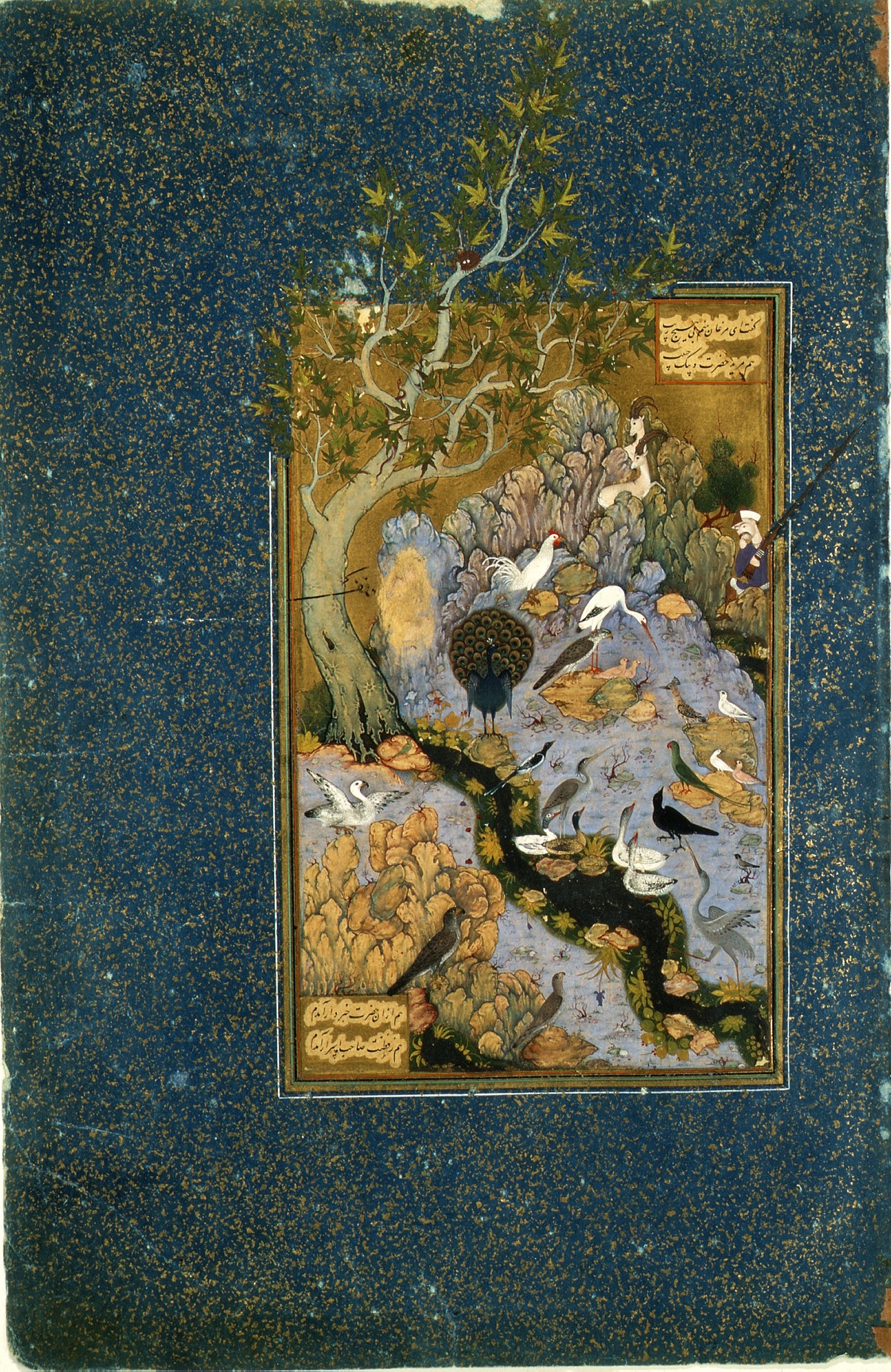

Habiballah of Sava. Concourse of The Birds, ca. 1600

Habiballah of Sava. Concourse of The Birds, ca. 1600

We sit in David Biespiel’s Republic Café: all of us together in the public space of democracy. It appeared in 2019, as American fascism made its perennial strut, less disguised than usual. At that point we’d endured two years of it. Lies spewed from the Leader’s mouth like flies from an open sewer, his followers enacting Hannah Arendt’s crisp formulation:

We sit in David Biespiel’s Republic Café: all of us together in the public space of democracy. It appeared in 2019, as American fascism made its perennial strut, less disguised than usual. At that point we’d endured two years of it. Lies spewed from the Leader’s mouth like flies from an open sewer, his followers enacting Hannah Arendt’s crisp formulation:

After my student days in Cambridge, in my professional life I have been to Britain many times, occasionally for lectures and conferences, but sometimes more formally on visiting assignments. The latter, except for the two terms at Trinity College, Cambridge, as a Visiting Fellow, have been more to Oxford and London School of Economics; this may be partly because for some time there was a relative decline in the quality of the Cambridge Economics Department after the internal troubles and the exit of some big names that I have alluded to before. In Oxford I have been on formal visits to All Souls College, St. Catherine’s College, and Nuffield College.

After my student days in Cambridge, in my professional life I have been to Britain many times, occasionally for lectures and conferences, but sometimes more formally on visiting assignments. The latter, except for the two terms at Trinity College, Cambridge, as a Visiting Fellow, have been more to Oxford and London School of Economics; this may be partly because for some time there was a relative decline in the quality of the Cambridge Economics Department after the internal troubles and the exit of some big names that I have alluded to before. In Oxford I have been on formal visits to All Souls College, St. Catherine’s College, and Nuffield College.

Nah. Let’s talk about our brains. The neocortex is where all our fancy thinking takes place. The neocortex wraps around the core of our brain, and if you could carefully unwrap it and lay it flat it would be about the size of a dinner napkin, and about 3 millimeters thick. The neocortex consists of 150,000 cortical columns, which we might think of as separate processing units involving hundreds of thousands of neurons. According to research at Jeff Hawkins’ company Numenta (and as explained in his fascinating recent book,

Nah. Let’s talk about our brains. The neocortex is where all our fancy thinking takes place. The neocortex wraps around the core of our brain, and if you could carefully unwrap it and lay it flat it would be about the size of a dinner napkin, and about 3 millimeters thick. The neocortex consists of 150,000 cortical columns, which we might think of as separate processing units involving hundreds of thousands of neurons. According to research at Jeff Hawkins’ company Numenta (and as explained in his fascinating recent book,  I assume that if your eye was drawn to this essay, then you are also troubled by feelings of rage. But I don’t want to be presumptuous—there are other reasons to read an essay that promises to tell you what to do with your anger. Maybe you think I have an agenda. Perhaps you have formed an idea of what my rage is about, and you disagree with that figment, and you are hate-reading these words right now, waiting for me to reveal the source of my own rage so that you can write a nasty comment at the end of this post or troll me on social media or try to cancel me or dox me or incite violence against me or come to my house and sneak onto my porch and stare balefully into my front windows or throw an egg at my car or trample deliberately on the ox-eye sunflowers that are bursting around my mailbox or put a bomb in my mailbox or disagree with me strenuously in your heart. There is a wide range of potential negative responses, and I don’t have time to list them all. The point here is that one must contend with them, and that is another reason to feel rage.

I assume that if your eye was drawn to this essay, then you are also troubled by feelings of rage. But I don’t want to be presumptuous—there are other reasons to read an essay that promises to tell you what to do with your anger. Maybe you think I have an agenda. Perhaps you have formed an idea of what my rage is about, and you disagree with that figment, and you are hate-reading these words right now, waiting for me to reveal the source of my own rage so that you can write a nasty comment at the end of this post or troll me on social media or try to cancel me or dox me or incite violence against me or come to my house and sneak onto my porch and stare balefully into my front windows or throw an egg at my car or trample deliberately on the ox-eye sunflowers that are bursting around my mailbox or put a bomb in my mailbox or disagree with me strenuously in your heart. There is a wide range of potential negative responses, and I don’t have time to list them all. The point here is that one must contend with them, and that is another reason to feel rage.