by Pranab Bardhan

All of the articles in this series can be found here.

In the early 1990’s I was a visiting fellow at St Catherine’s College and an academic visitor at Nuffield College in Oxford. At Nuffield College at that time two friends from my Cambridge student days were Fellows, Jim Mirrlees and Christopher Bliss. (I think Jim was mostly away during my visit, and graciously asked me to use his large office at Nuffield). The other person I used to see there off and on was Tony Atkinson who became the Warden of Nuffield shortly afterward. I knew Tony since our student days in Cambridge. Like me he also moved from one Cambridge to the other, to MIT, roughly around the same time. Both of us were heavily influenced by our teacher James Meade, though Tony never did a Ph.D. (as used to be the old British tradition—neither James Meade nor Joan Robinson had a Ph.D.) Tony did not follow Meade in the latter’s work on international trade, as I did, but in other respects he broadly followed on the footsteps of Meade, apart from sharing Meade’s personal characteristics of modesty, decency and a positive vision of the future. Tony was certainly among the best economists of my generation, with pioneering work on inequality, poverty, public policies, redistributive taxation, and welfare. He was also an advocate of Universal Basic Income. I had co-authored a chapter for the Handbook of Income Distribution that he co-edited with François Bourguignon, a French development economist friend of mine.

In the early 1990’s I was a visiting fellow at St Catherine’s College and an academic visitor at Nuffield College in Oxford. At Nuffield College at that time two friends from my Cambridge student days were Fellows, Jim Mirrlees and Christopher Bliss. (I think Jim was mostly away during my visit, and graciously asked me to use his large office at Nuffield). The other person I used to see there off and on was Tony Atkinson who became the Warden of Nuffield shortly afterward. I knew Tony since our student days in Cambridge. Like me he also moved from one Cambridge to the other, to MIT, roughly around the same time. Both of us were heavily influenced by our teacher James Meade, though Tony never did a Ph.D. (as used to be the old British tradition—neither James Meade nor Joan Robinson had a Ph.D.) Tony did not follow Meade in the latter’s work on international trade, as I did, but in other respects he broadly followed on the footsteps of Meade, apart from sharing Meade’s personal characteristics of modesty, decency and a positive vision of the future. Tony was certainly among the best economists of my generation, with pioneering work on inequality, poverty, public policies, redistributive taxation, and welfare. He was also an advocate of Universal Basic Income. I had co-authored a chapter for the Handbook of Income Distribution that he co-edited with François Bourguignon, a French development economist friend of mine.

Among Meade’s international trade students one of the most famous was Max Corden (who grew up in Australia after fleeing Nazi Germany), also a very decent cordial man, who was a Fellow at Nuffield College, but had left for US some years before my visit. I had known Max since his earlier Oxford days. Whenever we met we shared our experience and memories of our common teacher, James Meade. Max was of the opinion that whatever people later discovered to be important in international trade theory was somewhere in the dense prose of Meade’s two big volumes on international trade, published in the early 1950’s. Read more »

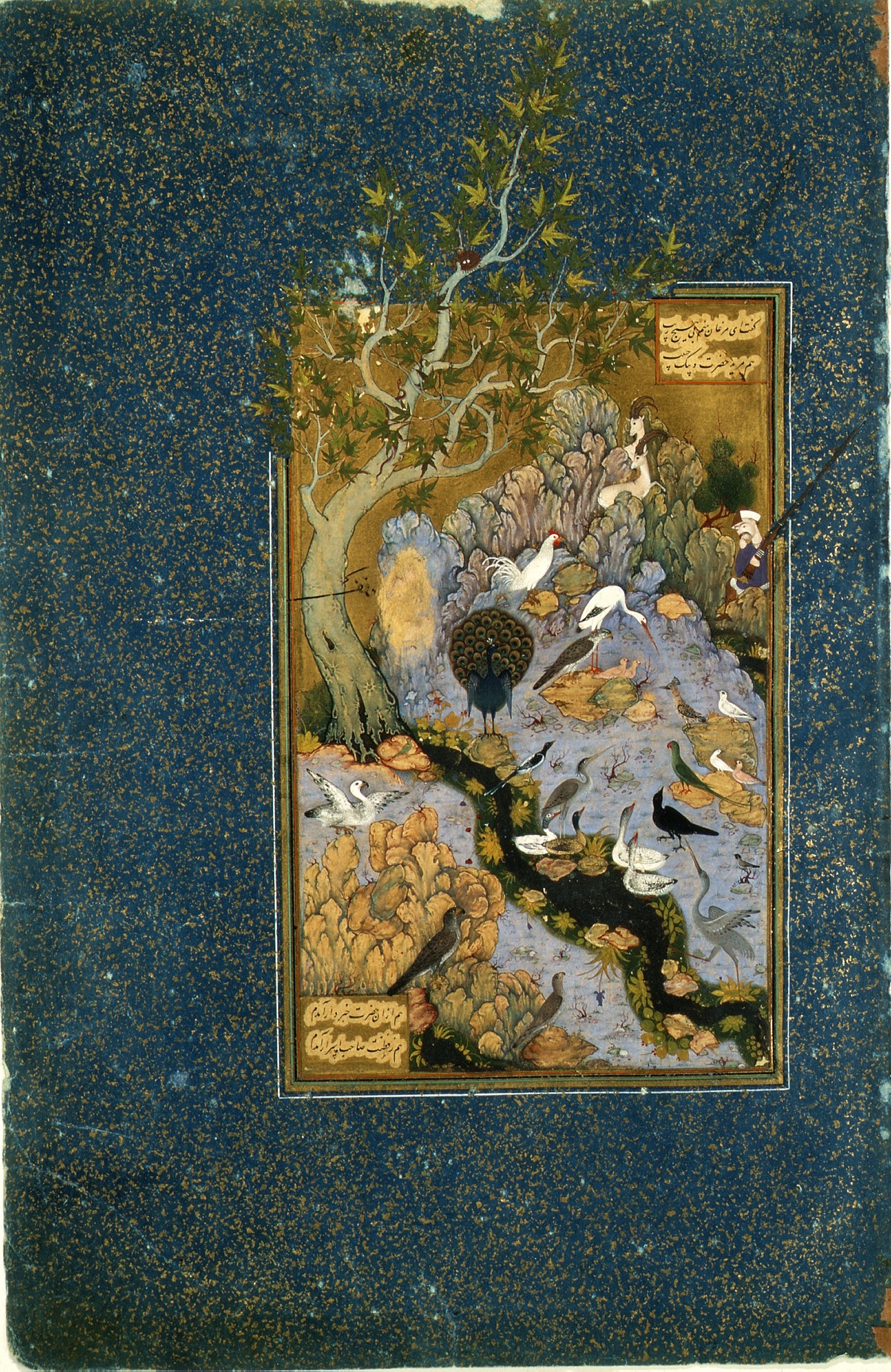

Habiballah of Sava. Concourse of The Birds, ca. 1600

Habiballah of Sava. Concourse of The Birds, ca. 1600

We sit in David Biespiel’s Republic Café: all of us together in the public space of democracy. It appeared in 2019, as American fascism made its perennial strut, less disguised than usual. At that point we’d endured two years of it. Lies spewed from the Leader’s mouth like flies from an open sewer, his followers enacting Hannah Arendt’s crisp formulation:

We sit in David Biespiel’s Republic Café: all of us together in the public space of democracy. It appeared in 2019, as American fascism made its perennial strut, less disguised than usual. At that point we’d endured two years of it. Lies spewed from the Leader’s mouth like flies from an open sewer, his followers enacting Hannah Arendt’s crisp formulation:

Nah. Let’s talk about our brains. The neocortex is where all our fancy thinking takes place. The neocortex wraps around the core of our brain, and if you could carefully unwrap it and lay it flat it would be about the size of a dinner napkin, and about 3 millimeters thick. The neocortex consists of 150,000 cortical columns, which we might think of as separate processing units involving hundreds of thousands of neurons. According to research at Jeff Hawkins’ company Numenta (and as explained in his fascinating recent book,

Nah. Let’s talk about our brains. The neocortex is where all our fancy thinking takes place. The neocortex wraps around the core of our brain, and if you could carefully unwrap it and lay it flat it would be about the size of a dinner napkin, and about 3 millimeters thick. The neocortex consists of 150,000 cortical columns, which we might think of as separate processing units involving hundreds of thousands of neurons. According to research at Jeff Hawkins’ company Numenta (and as explained in his fascinating recent book,  I assume that if your eye was drawn to this essay, then you are also troubled by feelings of rage. But I don’t want to be presumptuous—there are other reasons to read an essay that promises to tell you what to do with your anger. Maybe you think I have an agenda. Perhaps you have formed an idea of what my rage is about, and you disagree with that figment, and you are hate-reading these words right now, waiting for me to reveal the source of my own rage so that you can write a nasty comment at the end of this post or troll me on social media or try to cancel me or dox me or incite violence against me or come to my house and sneak onto my porch and stare balefully into my front windows or throw an egg at my car or trample deliberately on the ox-eye sunflowers that are bursting around my mailbox or put a bomb in my mailbox or disagree with me strenuously in your heart. There is a wide range of potential negative responses, and I don’t have time to list them all. The point here is that one must contend with them, and that is another reason to feel rage.

I assume that if your eye was drawn to this essay, then you are also troubled by feelings of rage. But I don’t want to be presumptuous—there are other reasons to read an essay that promises to tell you what to do with your anger. Maybe you think I have an agenda. Perhaps you have formed an idea of what my rage is about, and you disagree with that figment, and you are hate-reading these words right now, waiting for me to reveal the source of my own rage so that you can write a nasty comment at the end of this post or troll me on social media or try to cancel me or dox me or incite violence against me or come to my house and sneak onto my porch and stare balefully into my front windows or throw an egg at my car or trample deliberately on the ox-eye sunflowers that are bursting around my mailbox or put a bomb in my mailbox or disagree with me strenuously in your heart. There is a wide range of potential negative responses, and I don’t have time to list them all. The point here is that one must contend with them, and that is another reason to feel rage.