by Tim Sommers

Moral Grandstanding is using moral talk as way of drawing attention to oneself, seeking status, and/or trying to impress others with our moral qualities. Moral grandstanding is supposed, by some, to be a pervasive and dangerous phenomenon. According to psychologist Joshua Grubbs, for example, moral grandstanding exacerbated the COVID-19 crisis and is “part of the reason so many of us are so awful to each other so much of the time.”

Moral grandstanding is intimately related to virtue signaling, and both are, let’s face it, first and foremost internet problems – if they are problems at all. Since virtue signaling came first, it actually has a dictionary definition. The Cambridge Dictionary defines virtue signaling as “An attempt to show other people that you are a good person, for example by expressing opinions that will be acceptable to them, especially on social media.”

What’s the difference, then, between virtue signaling and moral grandstanding? Maybe, there isn’t one, or, maybe, it’s this. According to philosophers Brandon Warmke and Justin Tosi, the principal investigators on a multi-year Koch Foundation funded research program leading to their 2020 book, “Grandstanding: The Use and Abuse of Moral Talk,” grandstanding is about using “moral talk to dominate others”. So, virtue signaling is about fitting in, while moral grandstanding is about taking over. Read more »

If philosophy is not only an academic, theoretical discipline but a way of life, as many Ancient Greek and Roman philosophers thought, one way of evaluating a philosophy is in terms of the kind of life it entails.

If philosophy is not only an academic, theoretical discipline but a way of life, as many Ancient Greek and Roman philosophers thought, one way of evaluating a philosophy is in terms of the kind of life it entails.

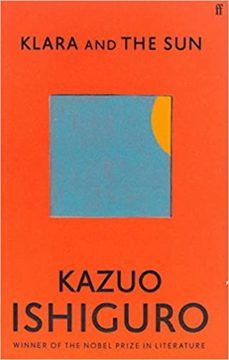

It’s still such a strange time as regards the Covid-19 pandemic. Most governments have lifted restrictions and lockdowns. However, new variants are still emerging and far too few people have been vaccinated globally to lend confidence for the health crisis’s resolution. With this in mind, I’ve been reading

It’s still such a strange time as regards the Covid-19 pandemic. Most governments have lifted restrictions and lockdowns. However, new variants are still emerging and far too few people have been vaccinated globally to lend confidence for the health crisis’s resolution. With this in mind, I’ve been reading  The Welcome Center museum isn’t exceptionally well-known. I often hear variations of the same phrase: “Oh, I’ve been coming to Breckenridge for years and never knew there was a museum back here!” It does get a lot of foot traffic, though, because (as its name implies) it is in the back of the Welcome Center building.

The Welcome Center museum isn’t exceptionally well-known. I often hear variations of the same phrase: “Oh, I’ve been coming to Breckenridge for years and never knew there was a museum back here!” It does get a lot of foot traffic, though, because (as its name implies) it is in the back of the Welcome Center building.

After LSE I have seen Jean Drèze mostly in India, usually in conferences in Delhi and Kolkata, and at Amartya Sen’s home in Santiniketan (where he used to stay whenever the two of them were writing books together). The Kolkata conferences were the annual ones that Amartya-da used to organize for some years, held usually at the Taj Bengal five-star hotel, which Jean would refuse to stay in. While others would take the 2-hour flight from Delhi to Kolkata, Jean would take the 24-hour train in the crowded second-class compartment. Then he’d call me and often stay with me in my Kolkata apartment. If Kalpana was around and it was winter she’d warm the bath water for him and arrange a comfortable raised bed for him; but Jean would refuse even those minor luxuries, and insist on taking cold showers and sleeping on the floor.

After LSE I have seen Jean Drèze mostly in India, usually in conferences in Delhi and Kolkata, and at Amartya Sen’s home in Santiniketan (where he used to stay whenever the two of them were writing books together). The Kolkata conferences were the annual ones that Amartya-da used to organize for some years, held usually at the Taj Bengal five-star hotel, which Jean would refuse to stay in. While others would take the 2-hour flight from Delhi to Kolkata, Jean would take the 24-hour train in the crowded second-class compartment. Then he’d call me and often stay with me in my Kolkata apartment. If Kalpana was around and it was winter she’d warm the bath water for him and arrange a comfortable raised bed for him; but Jean would refuse even those minor luxuries, and insist on taking cold showers and sleeping on the floor. A little while ago my friend Bethany requested that I write an essay on the following topic: “Can/should pedantry be reconstituted as a virtue, maybe particularly for women.” I filed it away on my list of possible future essay ideas, but like a

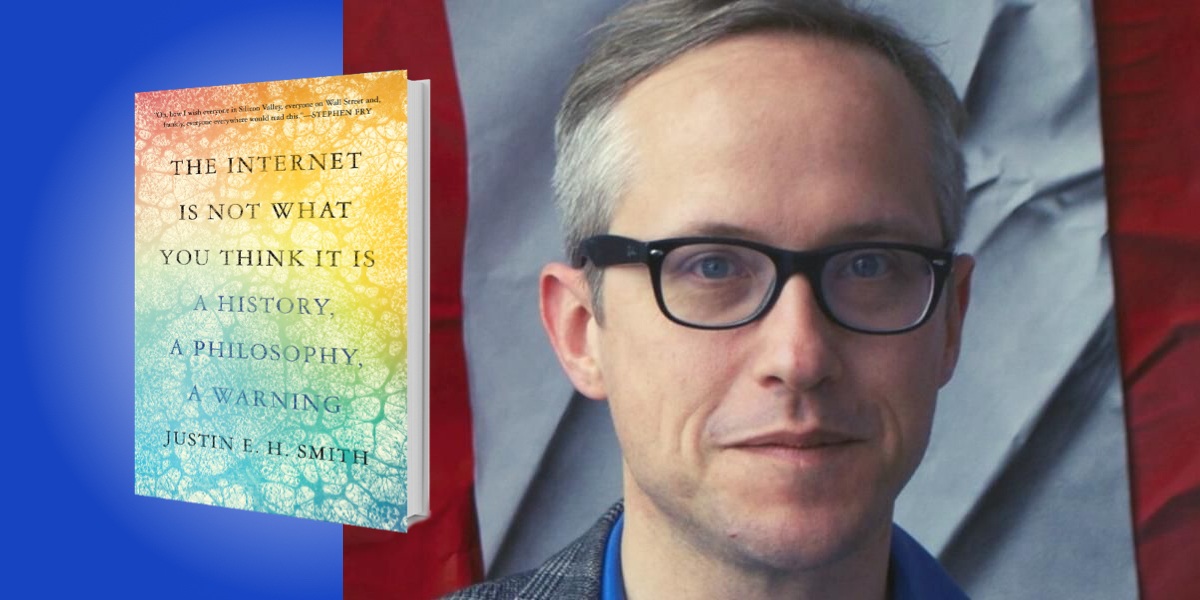

A little while ago my friend Bethany requested that I write an essay on the following topic: “Can/should pedantry be reconstituted as a virtue, maybe particularly for women.” I filed it away on my list of possible future essay ideas, but like a  Justin E. H. Smith’s recent book,

Justin E. H. Smith’s recent book,  I’m not sure what Americans were like in the 18th and 19th century, but they have to have been a lot tougher, less whining, less self-important and paradoxically more exceptional without thinking they were exceptional than Americans of today.

I’m not sure what Americans were like in the 18th and 19th century, but they have to have been a lot tougher, less whining, less self-important and paradoxically more exceptional without thinking they were exceptional than Americans of today.

Sughra Raza. Untitled, ca 2008.

Sughra Raza. Untitled, ca 2008.