by R. Passov

October 2019: Unnamed City, Central Africa – Day One

It’s nighttime. We tour the Unnamed City. Sebastian and I ride in the back of a black Toyota Land Cruiser. In front, Captain and Jannie, who for half his thirty years has been the only one who can drive Sebastian.

“I was in western Kenya,” I offer, “touring the farming made possible by seeds supplied by the non-profit, started by two young MBA’s from my country.”

“I am aware of the farms,” Sebastian says. “Are the farmers women?”

“Yes,” I say.

“Always women,” he says. “Always the women farm and the men leave.”

Dressed in clean blue jeans and a blue polo shirt, Jannie’s time in the city is measured by the belly he has grown since leaving the forest. Every time I look at him, he smiles. In the beginning I believe his smile is deference for the West.

“I found Jannie,” Sebastian explains, “after the last civil war. The one that cleared out the city, that destroyed all that he owned, pitting him against Captain. The same civil war that could start again at any moment.”

“Captain,” Sebastian adds, “was given to me by the army. A Lieutenant Colonel. Not just any Colonel. He is the Colonel sent by the President to find the last of the rebels from the civil war. Sent to find them in the jungle and to make sure they will never come back.”

In 1998 when Amartya Sen got the Nobel Prize it was a big event for us development economists. Even though the Prize was announced primarily for his contributions to social choice theory (in particular, his exploration of the conditions that permit aggregation of individual preferences into collective decisions in a way that is consistent with individual rights), the Prize Committee also referred to his work on famines and the welfare of the poorest people in developing countries. Even this fractional recognition of his work on economic development came after a long neglect of development economics in the mainstream of economics. The only other development economist recipients of the Prize had been Arthur Lewis and Ted Schultz simultaneously decades back.

In 1998 when Amartya Sen got the Nobel Prize it was a big event for us development economists. Even though the Prize was announced primarily for his contributions to social choice theory (in particular, his exploration of the conditions that permit aggregation of individual preferences into collective decisions in a way that is consistent with individual rights), the Prize Committee also referred to his work on famines and the welfare of the poorest people in developing countries. Even this fractional recognition of his work on economic development came after a long neglect of development economics in the mainstream of economics. The only other development economist recipients of the Prize had been Arthur Lewis and Ted Schultz simultaneously decades back. In June 1945, the American military appointed twenty-nine-year old Pat Lochridge mayor of Berchtesgaden, the tiny fairytale Bavarian town near the Austrian border crowded by Alps, where three thousand feet up, Hitler built his Eagle’s Nest retreat. “It is the intention of the Allies that the German people be given the opportunity to prepare for the eventual reconstruction of their life on a democratic and peaceful basis,” wrote the Allies at Potsdam.

In June 1945, the American military appointed twenty-nine-year old Pat Lochridge mayor of Berchtesgaden, the tiny fairytale Bavarian town near the Austrian border crowded by Alps, where three thousand feet up, Hitler built his Eagle’s Nest retreat. “It is the intention of the Allies that the German people be given the opportunity to prepare for the eventual reconstruction of their life on a democratic and peaceful basis,” wrote the Allies at Potsdam.  Physicists writing books for the public have faced a longstanding challenge. Either they can write purely popular accounts that explain physics through metaphors and pop culture analogies but then risk oversimplifying key concepts, or they can get into a great deal of technical detail and risk making the book opaque to most readers without specialized training. All scientists face this challenge, but for physicists it’s particularly acute because of the mathematical nature of their field. Especially if you want to explain the two towering achievements of physics, quantum mechanics and general relativity, you can’t really get away from the math. It seems that physicists are stuck between a rock and a hard place: include math and, as the popular belief goes, every equation risks cutting their readership by half or, exclude math and deprive readers of a deeper understanding. The big question for a physicist who wants to communicate the great ideas of physics to a lay audience without entirely skipping the technical detail thus is, is there a middle ground?

Physicists writing books for the public have faced a longstanding challenge. Either they can write purely popular accounts that explain physics through metaphors and pop culture analogies but then risk oversimplifying key concepts, or they can get into a great deal of technical detail and risk making the book opaque to most readers without specialized training. All scientists face this challenge, but for physicists it’s particularly acute because of the mathematical nature of their field. Especially if you want to explain the two towering achievements of physics, quantum mechanics and general relativity, you can’t really get away from the math. It seems that physicists are stuck between a rock and a hard place: include math and, as the popular belief goes, every equation risks cutting their readership by half or, exclude math and deprive readers of a deeper understanding. The big question for a physicist who wants to communicate the great ideas of physics to a lay audience without entirely skipping the technical detail thus is, is there a middle ground? Sughra Raza. Self-portrait in Reflected Morning Light, August 2, 2022.

Sughra Raza. Self-portrait in Reflected Morning Light, August 2, 2022.

If philosophy is not only an academic, theoretical discipline but a way of life, as many Ancient Greek and Roman philosophers thought, one way of evaluating a philosophy is in terms of the kind of life it entails.

If philosophy is not only an academic, theoretical discipline but a way of life, as many Ancient Greek and Roman philosophers thought, one way of evaluating a philosophy is in terms of the kind of life it entails.

It’s still such a strange time as regards the Covid-19 pandemic. Most governments have lifted restrictions and lockdowns. However, new variants are still emerging and far too few people have been vaccinated globally to lend confidence for the health crisis’s resolution. With this in mind, I’ve been reading

It’s still such a strange time as regards the Covid-19 pandemic. Most governments have lifted restrictions and lockdowns. However, new variants are still emerging and far too few people have been vaccinated globally to lend confidence for the health crisis’s resolution. With this in mind, I’ve been reading  The Welcome Center museum isn’t exceptionally well-known. I often hear variations of the same phrase: “Oh, I’ve been coming to Breckenridge for years and never knew there was a museum back here!” It does get a lot of foot traffic, though, because (as its name implies) it is in the back of the Welcome Center building.

The Welcome Center museum isn’t exceptionally well-known. I often hear variations of the same phrase: “Oh, I’ve been coming to Breckenridge for years and never knew there was a museum back here!” It does get a lot of foot traffic, though, because (as its name implies) it is in the back of the Welcome Center building.

A little while ago my friend Bethany requested that I write an essay on the following topic: “Can/should pedantry be reconstituted as a virtue, maybe particularly for women.” I filed it away on my list of possible future essay ideas, but like a

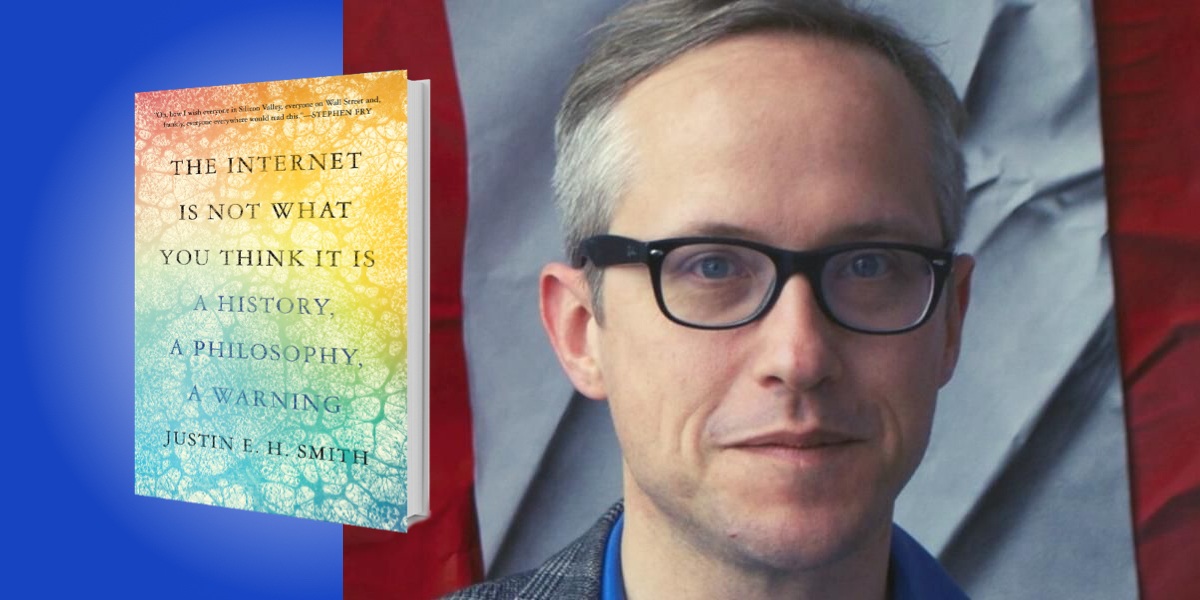

A little while ago my friend Bethany requested that I write an essay on the following topic: “Can/should pedantry be reconstituted as a virtue, maybe particularly for women.” I filed it away on my list of possible future essay ideas, but like a  Justin E. H. Smith’s recent book,

Justin E. H. Smith’s recent book,