by Ethan Seavey

My grandmother’s bird of choice is the rooster. She was raised in rural Kentucky and now lives in rural Wisconsin. She collects all sorts of roosters (and, by extension, some hens): wall art, printed dish towels, ceramic statues as small as a pinky and as large as a lamp, coin bowls and blankets and something nostalgic in each one.

My grandmother’s bird of choice is the rooster. She was raised in rural Kentucky and now lives in rural Wisconsin. She collects all sorts of roosters (and, by extension, some hens): wall art, printed dish towels, ceramic statues as small as a pinky and as large as a lamp, coin bowls and blankets and something nostalgic in each one.

If you don’t mind stepping briefly into her condo, we can see what it’s like. Eyes everywhere. Thoughtless, energetic eyes. Suspicion and preparedness. A rooster’s eye is life because it is anxiously awake, unsure why, but it is safe because it is always aware of sources of suspicion; suspicion, of course, comes from an abundance of anxiety. So those eyes don’t think much about what they’re watching. I’m sure you’ll find it hard to find hundreds of rooster eyes in your peripheral vision, but you’ll get used to it. If you feel overwhelmed, you can look outside her large windows, you can see the small and glassy lake with sailboats gliding over its surface like razors through taut fabric.

My mother’s bird of choice is the crow. She unconsciously developed an uncanny connection with them. It started during our group quarantine, after the onset of the pandemic. We spent April through May isolated in our ski cabin. We had no friends there so we could not be tempted to socialize. We could social distance easily, with the majority of the houses nearby sitting empty, their owners waiting for the ski resort to reopen. Read more »

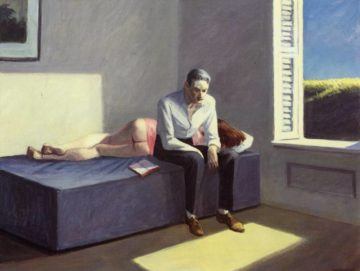

Sughra Raza. Shadow Self-Portrait in a Reflection of a Window in a Window.

Sughra Raza. Shadow Self-Portrait in a Reflection of a Window in a Window.  A couple of years ago I briefly became famous for hating Vancouver. By “famous” I mean that a hundred thousand people or so read

A couple of years ago I briefly became famous for hating Vancouver. By “famous” I mean that a hundred thousand people or so read

It was announced last week that scientists have integrated neurons from human brains into infant rat brains, resulting in new insights about how our brain cells grow and connect, and some hope of a deeper understanding of neural disorders.

It was announced last week that scientists have integrated neurons from human brains into infant rat brains, resulting in new insights about how our brain cells grow and connect, and some hope of a deeper understanding of neural disorders.  Visualize a purple dog, the exercise said. Imagine it in great detail; picture it approaching you in a friendly way. So I did. I thought of a spaniel: long silky ears, beautiful coat, all a nice lilac color. Pale purple whiskers. The dog was friendly but not effusive. I’m not a dog person, but I wouldn’t have minded meeting this dog. All right, now what? The exercise went on to say something along the lines of “Wonderful! If you can visualize that purple dog, can’t you imagine your own life as being full of amazing possibilities?”

Visualize a purple dog, the exercise said. Imagine it in great detail; picture it approaching you in a friendly way. So I did. I thought of a spaniel: long silky ears, beautiful coat, all a nice lilac color. Pale purple whiskers. The dog was friendly but not effusive. I’m not a dog person, but I wouldn’t have minded meeting this dog. All right, now what? The exercise went on to say something along the lines of “Wonderful! If you can visualize that purple dog, can’t you imagine your own life as being full of amazing possibilities?”

The Fate of the Animals: On Horses, the Apocalypse, and Painting as Prophesy (Three Paintings Trilogy), by Morgan Meis, Slant

The Fate of the Animals: On Horses, the Apocalypse, and Painting as Prophesy (Three Paintings Trilogy), by Morgan Meis, Slant Scheduled departure at Dulles came and went as we waited for the last passenger to board. Although the non-smoking section in the rear cabin was full, the smoking section where I sat was half empty. Death by asphyxiation on the flight to Paris was a distinct possibility but with three empty, adjacent seats in the centre nave there was some chance that my obituary might read, “She died peacefully, in recumbent sleep.”

Scheduled departure at Dulles came and went as we waited for the last passenger to board. Although the non-smoking section in the rear cabin was full, the smoking section where I sat was half empty. Death by asphyxiation on the flight to Paris was a distinct possibility but with three empty, adjacent seats in the centre nave there was some chance that my obituary might read, “She died peacefully, in recumbent sleep.” Indifference is an attitude first theorised as a philosophical stance by ancient Greek Stoic philosophers from the 3rd century BC. It was conceived as the right attitude to cultivate in reaction to indifferent things. What was surprising were the things the Stoics considered to be indifferent and hence require us to be indifferent to. Not your usual ‘whether the number of hairs on your head is odd or pair’, or the number of billions of stars in the galaxy, or even what colour underwear your boss wears – though in some circumstances, the latter can start becoming titillating. And titillation is of course what it’s all about. It’s the tickle that spurs the Stoic to resist it. Resisting what exactly? Feeling, uncontrolled gratification, heart-melting, giving in, touching, kiss-&-make-up-ing.

Indifference is an attitude first theorised as a philosophical stance by ancient Greek Stoic philosophers from the 3rd century BC. It was conceived as the right attitude to cultivate in reaction to indifferent things. What was surprising were the things the Stoics considered to be indifferent and hence require us to be indifferent to. Not your usual ‘whether the number of hairs on your head is odd or pair’, or the number of billions of stars in the galaxy, or even what colour underwear your boss wears – though in some circumstances, the latter can start becoming titillating. And titillation is of course what it’s all about. It’s the tickle that spurs the Stoic to resist it. Resisting what exactly? Feeling, uncontrolled gratification, heart-melting, giving in, touching, kiss-&-make-up-ing.