by Mindy Clegg

In their oft-cited classic examination of the modern mass media, Manufacturing Consent, Edward Herman and Noam Chomsky described modern American news media thusly: “The mass media serve as a system for communicating messages and symbols to the general populace. It is their function to amuse, entertain, and inform, and to inculcate individuals with the values, beliefs, and codes of behavior that will integrate them into the institutional structures of the larger society. In a world of concentrated wealth and major conflicts of class interest, to fulfill this role requires systematic propaganda.”1 In other words, democratic states use privately-owned media as a means of social control. Private corporations own and operate media outlets and they work with the US government because the power of the state dovetailed with their own economic interests.

The groundwork for this state of affairs emerged out of intellectual discourse in the early days of mass media. In the wake of the first world war, prominent intellectuals like Walter Lippmann and Edward Bernays suggested a set of strategies for channeling democratic impulses expanding in the United States to better align with the wishes of the ruling classes.2 Such analysis was and continues to be necessary, as many are unaware of the very real pitfalls of corporate media in democratic societie. These systems are now often globalized which shape our understanding of the past and present that we must understand in hopes of changing them. But we must also wonder if the singular focus on these systems of control lead to the feelings of hopelessness that many of us feel about our institutions these days. As much as describing what dominates us feels cathartic, focusing only on the systems of control and not on resistance makes the problem seem insurmountable. I argue that we need to look for the cracks as much as describe the problem posed by corporate medi. Understanding the democratic alternatives within and outside of the mainstream production of popular culture can help us to see these cracks. Read more »

Sughra Raza. NYC, April 2023.

Sughra Raza. NYC, April 2023.

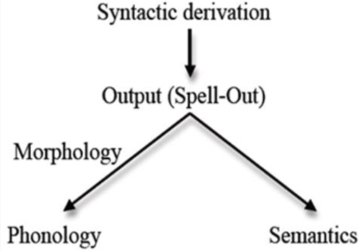

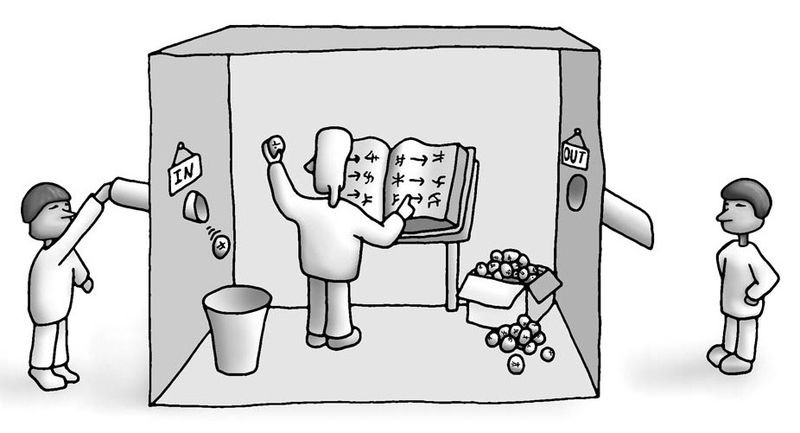

Despite many people’s apocalyptic response to ChatGPT, a great deal of caution and skepticism is in order. Some of it is philosophical, some of it practical and social. Let me begin with the former.

Despite many people’s apocalyptic response to ChatGPT, a great deal of caution and skepticism is in order. Some of it is philosophical, some of it practical and social. Let me begin with the former.

How intelligent is ChatGPT? That question has loomed large ever since

How intelligent is ChatGPT? That question has loomed large ever since

Environmentalists are always complaining that governments are obsessed with GDP and economic growth, and that this is a bad thing because economic growth is bad for the environment. They are partly right but mostly wrong. First, while governments talk about GDP a lot, that does not mean that they actually prioritise economic growth. Second, properly understood economic growth is a great and wonderful thing that we should want more of.

Environmentalists are always complaining that governments are obsessed with GDP and economic growth, and that this is a bad thing because economic growth is bad for the environment. They are partly right but mostly wrong. First, while governments talk about GDP a lot, that does not mean that they actually prioritise economic growth. Second, properly understood economic growth is a great and wonderful thing that we should want more of. Sughra Raza. Untitled. April 1, 2023.

Sughra Raza. Untitled. April 1, 2023.