by Ada Bronowski

There is something bewildering about life in Paris under Nazi occupation: theatres, cinemas, cabarets and cafés in full swing, swarming with Nazi officials mingling with the locals, when, all the while, people are arrested in broad daylight, dragged out of their apartments, tracked, tortured and killed for being Jewish or communist, active in the resistance, gay or just for being in the wrong place at the wrong time. In the midst of food shortages and curfews, the champagne galas, dinners at Maxim’s, lobster at the Etoile de Kleber, the thirst for entertainment and the possibilities for quenching it multiplied. A newly published French book by the writer, producer and playwright Pierre Laville, La Guerre Les Avait Jetés Là (literally translated: The war threw them there, Robert Laffont, 2023), delves with compassion and understanding into the ambiguities of living in Nazi-invaded Paris focusing on the ins and outs of one of the most important theatrical institutions in France, the Comédie-Française.

France’s national theatre founded by Louis XIV in 1680 re-opened in 1941, (closed since September 1939) with Pierre Corneille’s Le Cid. A rallying cry if ever there was, the play tells the story of the loves and wars of Don Rodrigue defending the kingdom of Spain against the Moors. “We set out five hundred, but through swift support, we soon became three thousand when we reached the port”[1] – a memorable line which neither the Germans nor the French collaborationist government were keen to have ringing in the ears of the Parisians who filled the house night after night. The director, Jacques Copeau, was fired.

The subtle message set the tone, regardless, for the next three years at le Français – as the Comédie-Française is familiarly called, short for le Théâtre-Français. A tone neither of overt resistance, nor submissive passivity, but a bit of both and something in between. Laville’s portrait of the stars and future stars from the backstage to the front rows is at one and the same time, infuriating and glorious, a mirror of the ambiguities of life under enemy occupation, filled with hidden heroics and overly peppered with lily-livered indifference. The characters of the book are familiar names but not usually painted in these colours: from star actresses Marie Bell and Madeleine Renaud to burgeoning maîtres-à-penser Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, who, (as yet known only within a small côterie of intellectuals), would forge the notion of passive resistance as absolute freedom, to mavericks of innocence and idealism Albert Camus and Juliette Greco – all these greats and future greats are caught red-handed as it were, face to face with the worst of times which, each in their own way, because of their exceptional temperaments, they resolve to make the best of times; that is, live life meaningfully.

From 1941 to 1944, le Français was the beating heart of French cultural life to which converged many of the celebrities and intellectuals of the day on and off stage – as also the German officers from the Propaganda-Staffel who had a right of veto on the plays performed, and could reserve the venue at whim, for German-only productions. Of course, there were other theatres too, over 400 venues were open and thriving during the war[2]. But the Comédie-Française is the jewel in the crown – where all the new authors wish to have their plays performed. Sartre tried with his first play, Les Mouches which he wanted the young Jean-Louis Barrault, freshly arrived at the Comédie-Française to stage, but neither Sartre nor Barrault were established enough to impose it. Instead, the play premiered, in June 1943, at the Théâtre de la Cité to diminutive success. But it is to the Comédie-Française that Goebbels sends German companies to perform, as in April 1943 when a company from Munich came to perform Goethe in German.

The actors and administrators of the Comédie-Française were warmly invited to attend the show as also the drinks party– ‘warmly’ meaning it was risky not to. And so they did – though Madeleine Renaud for one, felt too ill to go out that day, and her husband, J-L. Barrault had, naturally, to stay and look after her.

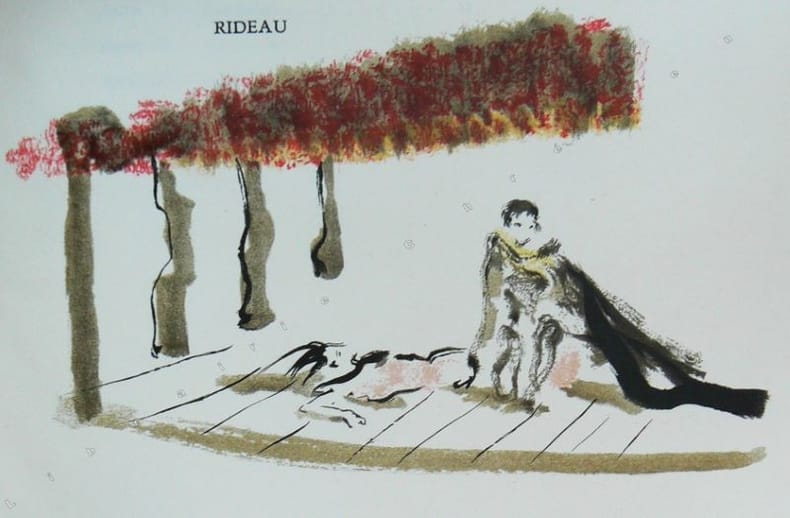

The company wad forced to accept such peremptory diktats from the Nazis, though it meant having to stop short their own rehearsals, in this case, for the imminent premiere of Jean Cocteau’s new play Renaud and Armide, a fantastical tragedy set at the time of the Crusades in which the witch Armide sacrifices herself for the sake of her love for king Renaud who goes on to free Jerusalem. Unlike with Sartre, Cocteau’s play had been accepted by the reading committee of the company, pending certain requested modifications, as also the rejection of Cocteau’s request that Renaud be played by his lover, the actor Jean Marais – too involved in film, when le Français demanded devotion to the stage.

Why Cocteau and not Sartre? The question is greater than the sum of its parts, but the choice here is reflective of the position of the Comédie-Française at the time: more dream-searching than intellectual, and – certainly at the time – less incline to risk big on a relatively unknown young author with overtly political inclinations. Sartre’s Les Mouches, undercover of the ancient Greek myth of Orestes killing his mother, charges the ancient plotline with a modern twist: no longer about avenging the murdered father but liberating an enslaved sister. The façade-desire to maintain le Français as an a-political space, an enchanted dream world which sublimates despair and sacrifice into impossible love stories, is a constant in the artistic choices of the company during the war, peaking with its production of Paul Claudel’s The Satin Slipper in 1943, a huge production premiered under Barrault’s bold staging in November 1943.

During the war, not only did the Comédie-Française thrive, with daily matinées and evening shows, maintaining its principle of ‘alternation’ – never the same play two nights in a row and a constant switch between classical and modern pieces – but it also harboured, in concentrated form, the raging battles (both physical and in the mind) that were tearing the French nation apart. To collaborate or not to collaborate? To suffer – passively – the slings and arrows ..? or to take arms..? It is not by chance that Hamlet, (in alternation) is played 49 times in the sole year 1942, with a Hamlet incarnated by the young, new recruit Jean-Louis Barrault, fresh from the avant-guard rive gauche (the Comédie-Française is establishment rive droite). The same year, Ernst Lubitsh made the film comedy To be or Not to be which no one saw in France since American films were banned in Europe. But the parallel is revelatory in the contrast between three perspectives on reality at the time and three readings of Hamlet: the cynical unrealistic comedy where Lubitsch’s crew of resistance-assisting actors save the day against Hitler, the tragic realism of Hamletian indecision as it was played on stage that year, and the real-life emergency both these versions echo, that of the necessity to actually answer the question and take sides, which millions of people suddenly faced.

An added aspect of exceptionalism surrounding the Comédie-Française and the Paris entertainment scene more generally is that, unlike what Lubitsch shows in his wonderful film, the Nazis in Poland did not leave local theatres any autonomy whatsoever; the latter operated under direct German control[3]. In France, both because the Germans’ cultivated a love (or pretence of love) for French Culture and because the Vichy government proved so eager to assist, the collaborationist system created a twice-removed German supervision and a margin of autonomy for the theatres despite the censure of the Propaganda-Staffel. This situation, compared to other invaded countries frames French collaboration in exceptional terms: impossible, morally, to be complacent and impossible, in practice, not to be complacent.

Barrault’s Hamlet is a bombshell in the French history of the performance of the play whose last memorable interpreter before Barrault was…Sarah Bernhardt! The Lady Gaga of the late 19th– early 20th centuries had had an adaptation of the play written for her, translated by the playwright Eugene Morand (father of the novelist Paul Morand) and poet Marcel Schwob, and which suffused the Dane with a hunger for vengeance as a larger-than-life double of his female interpreter. Bernhardt’s version however, was ‘tainted’ by the Jewisheness of Marcel Schwob and of the great lady herself, and so the 1942 version at the Comédie-Française is performed in the translation of the Swiss writer Guy de Pourtalès with a Hamlet who is hesitation incarnate.

Barrault’s Hamlet is a bombshell in the French history of the performance of the play whose last memorable interpreter before Barrault was…Sarah Bernhardt! The Lady Gaga of the late 19th– early 20th centuries had had an adaptation of the play written for her, translated by the playwright Eugene Morand (father of the novelist Paul Morand) and poet Marcel Schwob, and which suffused the Dane with a hunger for vengeance as a larger-than-life double of his female interpreter. Bernhardt’s version however, was ‘tainted’ by the Jewisheness of Marcel Schwob and of the great lady herself, and so the 1942 version at the Comédie-Française is performed in the translation of the Swiss writer Guy de Pourtalès with a Hamlet who is hesitation incarnate.

Jean-Louis Barrault, as an artist – who would single-handedly renew theatrical practices in the post-war era in France and around the world – embodies the status le Français takes on in these war years: the boldness in inventiveness under cover of a patina of classicism that stands for a naked humanism in all its frailty, sending sublimated messages that the semi-ironic semi-tragic motto of Paul Claudel’s The Satin Slipper :“the worst is not always certain” encapsulated.

With the characters of his bookv – all real-life actors of cultural life under Nazi occupation – Laville analyses the full array of interpretations of the art of escapism. Different interpretations for different people. And the transfer from heroes and villains on stage to real life actions, far from being straight-forward proved messy: in some cases, damning, in others more heroic than fiction. Life did not imitate art.

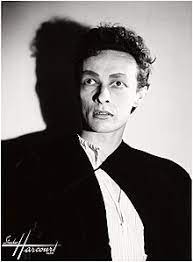

Cocteau justified his evenings spent in the company of Germans, by claiming ‘[his] world was elsewhere’, referring to the world of art, beauty and the purity of love which he created to our delight in his films and writings. This sort of mystical Platonism – the claim, that is, that the world around us is not real, and therefore need not trouble us, has no doubt, a great deal of attraction, but it cannot be an infallible key to life. One night in 1941 – as Laville recounts it – Max Jacob, also poet, painter of fabulous dreams and novelist, friend and ex-lover of Cocteau’s, but unlike him, Jewish (though converted), and therefore in hiding outside of Paris, returns to Parisat the risk of his life, near the Palais-Royal where Cocteau lived. Max Jacob feared that, not having destroyed all of his correspondence, the name of Cocteau might be found amongst his things and compromise his friend. That night, he waited in the freezing staircase outside Cocteau’s apartment to warn him. But Cocteau did not return home, spending it at a costume party held at the Count of Beaumont’s hôtel particulier.

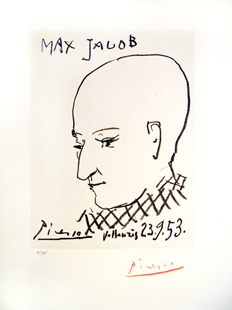

Cocteau was in his world of beauty and art, Max Jacob made it back to hiding that time round but would be caught in February 1944, and died a few days later at Drancy, in freezing conditions, awaiting transit to Auschwitz. True enough, there were efforts from Cocteau, Sacha Guitry, Charles Trenet (all mild collaborationists) to put pressure on their German friends to save the great poet Max Jacob – to no avail. Picasso, Jacob’s long-standing friend back from the days in Montmartre before and after the First World War, refused to even sign the petition, though organising, once Max Jacob’s death became known in march 1944, a memorial event, staging one of his plays under one of Picasso’s portrait of the poet.

Cocteau was in his world of beauty and art, Max Jacob made it back to hiding that time round but would be caught in February 1944, and died a few days later at Drancy, in freezing conditions, awaiting transit to Auschwitz. True enough, there were efforts from Cocteau, Sacha Guitry, Charles Trenet (all mild collaborationists) to put pressure on their German friends to save the great poet Max Jacob – to no avail. Picasso, Jacob’s long-standing friend back from the days in Montmartre before and after the First World War, refused to even sign the petition, though organising, once Max Jacob’s death became known in march 1944, a memorial event, staging one of his plays under one of Picasso’s portrait of the poet.

Did that night in the freezing staircase really happen? Laville’s sole witness is Marie Bell who bumps into Max Jacob by accident, on her return walk from an evening at the writer Colette’s, nearby. The book is not a history book in the academic sense, but it is a book written by a man who has spent his life in the theatre, known personally many of the protagonists of his book and presents an empathetic understanding of a psychological complexity that one might too hastily judge.

After the liberation of Paris, at the end of 1944, the company ‘purged’ a handful of its actors for collaboration, though for the most part, the shaming did not last: from Mary Marquet, a huge star of the company since the 1930s, who began a new career in the popular theatres of the boulevard and in nascent television, to André Burnot who had a thriving career in the cinema of the 1950s – a career, in his case, which only the New Wave cinema (Nouvelle Vague), with its assassination of the post-war film production, put a true ending to.

But by 1946, after a year in which three different directors came and went at the Comédie-Française, eight of the greatest stars of the company decided to leave, claiming an independence which, by the statutes imposed in 1680 at the creation of the company and till then never breached, was unheard of. Jean-Louis Barrault and Madeleine Renaud left to create their own company, the world-famous Compagnie Renaud-Barrault, Marie Bell, the last of the great tragedians, together with her partner Jean Chevrier left, she, to direct her own theatre, he, to pursue a career in film; other actors left in their wake to join either one of these new paths or further trails of independence. This exodus left the Comédie-Française halved in number but also frames the war years as an exceptional moment, where new and old, corruption and purity, elitism and the people, rubbed shoulders in a strange cohabitation.

During the three years of Nazi-supervised life at the Comédie-Française, some of the great masterpieces of French theatre of the 20th century were performed, making the Comédie-Française, the epicentre of modernism in showcasing new writing (by Jean Cocteau, Paul Claudel, François Mauriac amongst others); in new approaches to stage direction (with Jean-Louis Barrault, actor and director-extraordinaire); in stage design with painters such as Lucien Coutaud or Christian Bérard.

The classics were also re-enchanted, most famously Phaedra by Jean Racine, created in 1677 and performed in 1942 for a continuous run till 1944 by Marie Bell in the title role, directed by Barrault. It was a unanimous sensation first and foremost because the director took the decision to have the actors enunciate the 12-syllable alexandrins verses naturally and not with the traditional declamation which had been the absolute standard for the past three hundred years, reaching its peak with the great Sarah Bernhardt. Marie Bell, who had seen Bernhardt perform and was considered her heir, broke with this august tradition, and spoke the verse with sublime passion certainly, but the kind of sublime passion that speaks words naturally with an ordinary diction. It may seem hard to imagine now what a shockwave this created but shockwave it was[4].

And that is how it was: on stage, a fulcrum of creativity and perfectionism; beneath the surface: smouldering ambiguities and tensions in adapting to a regime as invasive as it was oppressive. As argued in a 1998 academic work, this fine-tuned equilibrium is the product of the le Français’ family ethics: love-hate inside, unified solidarity outside, under the masterful directorship of J-L. Vaudoyer[5]. But there is also a deeper dimension, related to the very essence of theatre. In a conversation that Laville invents or transcribes from the memories of Jean Chevrier and Marie Bell, the former asks his future wife “where does catharsis begin, where does it end?”. It is theatre’s endemic obsession with purity and purification that made the political and historical post-collaborationist purification trivial and the one which traversed and shook theatrical practice to its core so visceral and transformative, leading to the creation of the Renaud-Barrault company and the Théâtre Populaire of Jean Vilar to name but two of the most well-known developments of post-war theatre.

Along the corridors, from one dressing room to another, the slimiest of collaborationists rubbed shoulders, unbeknownst, with the Resistance. The day for instance, a young man is dragged out of star actor Maurice Escande’s dressing room, who couldn’t resist such a fortuitous quickie, when in fact the militia were looking for a recently parachuted British member of the Resistance. Threatened for indecent sexual practices prohibited by law, the actor names a number of high-ranking Vichy and German dignitaries who are close friends, and declares he has, what is more, ‘nothing to do with politics’. Marie Bell vouches for Escande. The young man is taken away, to be interrogated and tortured by the Gestapo. But, in truth, he was lurking around the theatre for a reason. He had a message to deliver to ‘Elisabeth’.

No one knows who ‘Elisabeth’ is, though she is standing in the corridor, talking down to the officers and in a rush because people are waiting for her for rehearsals. For ‘Elisabeth’ is the Resistance code name of Marie Bell. As volcanic in life as her Phaedra was on stage, she lived a double if not triple or quadruple life during the war. Creating some of the most memorable plays of the times, she was also a liaison for the Resistance, hiding Jewish families above her flat on the Champs-Elysées, taking in fugitives and passing on false identity papers. When Jean Chevrier, her partner, fifteen years her junior, learns indirectly that ‘Elisabeth’ is his Marie, and that this is why she was behaving so secretively which is why he had requested a separation, the stakes to reconquer her grow higher than ever. ![[Le père jésuite (Maurice Donneaud) sur l'épave désemparée]](https://bibliotheques-specialisees.paris.fr/in/rest/Thumb/image?id=h%3A%3Aark%3A%2F73873%2Fpf0001664687%2F0001&size=256&ct=true&siteId=mainSite)

At the same time, Marie Bell was close friends with film-star Arletty, who had an open relationship with a German officer, and Raimu, the beloved actor from the cinema of Marcel Pagnol, who is openly sympathetic to the Nazis and whom Marie Bell got to join the Comédie-Française in 1943. She was also close friends with Louis-Ferdinand Celine who dreamt of writing for her and wrote her admiring love letters, all the while schizophrenically torn between his maniacal antisemitism and his hatred for the Germans.

If sides had to be taken, they were taken in the shadows. Laville suggests as much also in how, after the war, though Marie Bell was decorated with the Légion d’Honneur by the General de Gaulle for her contribution to the Resistance, she always kept quiet about her resistance activities, like other figures from the Comédie-Française (in particular Pierre Dux, the director from 1946, who, despite his known participation in the Resistance, says almost nothing about the war years in his autobiography). There is ultimately a feeling of unease, a sense of disproportion between the enormity of the horror of what was happening and the singular acts of however extreme bravery that were performed; a sense of not having done enough or what really should have been done. There is no purity in life.

[1] P.Corneille, Le Cid (1637), act iv, sc.3: “nous partîmes cinq cent, mais par un prompt renfort,

nous nous vîmes trois mille en arrivant au port”

[2] See E. Arly, Nouvelle Histoire de l’Occupation, (2019), Paris: Perrin, esp. chap. 6.

[3] See J.Biernat, K. Czerska and J. Figiel (eds.), A History of Polish Theatre (2021), CUP, chap. 9.

[4] A reprisal of the production with the same cast, though now as part of the Marie Bell Company in 1947 on tour in Uruguay has been recorded and can be listened to thanks to the INA-archive and France Culture.

[5] See M.A. Joubert, La Comédie-Française Sous l’Occupation, (1998), Tallendier.