by Herbert Harris

This year’s Black History Month is different.

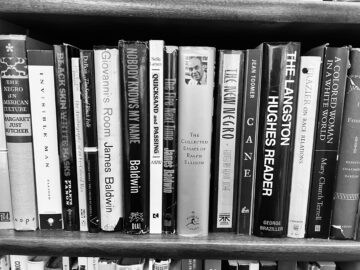

Black history itself has become contested. Not debated at the margins but questioned at its core. School curricula are scrutinized, and institutions that preserve Black memory are accused of being “divisive.” Should Black history exist, or should it disappear, erasing its many uncomfortable truths and leaving a more homogeneous national narrative?

Narratives are what hold us together as individuals and as societies. To have the wholeness and continuity essential to our survival, our stories must be heard, recognized, and validated by others. Identity is not a monologue in an empty room; it requires an audience and a full cast.

History is our shared narrative. It is how a nation understands what has happened and who it is. It is also how we relate to those who came before us. To deny or erase significant portions of that history is not merely to rearrange a syllabus. It distorts the self-understanding of the entire society. A narrative that excludes central truths becomes brittle. It depends on selective memory and strategic forgetting. That society’s connections to reality inevitably fray, eventually breaking.

As a psychiatrist, I have spent much of my professional life listening to narratives. Read more »