Category: Recommended Reading

Surviving Change in the Age of Alternative Facts

From McGill-Queen’s University Press:

Q: One of the central arguments of your book is that the “greatest emergency is the absence of emergency.” Could you please clarify this in relation to the ongoing pandemic caused by the coronavirus?

Q: One of the central arguments of your book is that the “greatest emergency is the absence of emergency.” Could you please clarify this in relation to the ongoing pandemic caused by the coronavirus?

Santiago Zabala: This thesis does not mean that a crisis such as the coronavirus is not a fundamental emergency that we must confront at all levels. It simply suggests the greatest emergency are the ones we do not confront. These include, among others, economic inequality, refugee crises, and climate change. Despite the warnings of scientists and activists since the 1970s, climate change is responsible for the death of seven million human beings every year because of air pollution. We can only hope climate change might also become an “emergency,” fought with the same unified purpose by many people as is now. What is dramatic about COVID-19 is that it was an “absent emergency” until very recently; just one year ago the WHO director-general, Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, warned us that the “threat of pandemic influenza is ever-present.” Unfortunately we did not listen and now we find ourselves facing an existential threat.

More here.

The Treaty of Westphalia

The Mathematician and the Mystic

David Guaspari at The New Atlantis:

In The Weil Conjectures Karen Olsson presents her remarkable subjects as creatures from a fairy tale: “Once there were a brother and sister who devoted themselves to the search for truth. A brother who spent his long life solving problems. A sister who died before she could solve the problem of life.” The sister was Simone Weil (pronounced “vay”), a philosopher and political activist who died in 1943 at age thirty-four and gained fame with the posthumous publication of works, assembled from her voluminous notebooks, on society, justice, and the mystical life of faith. Her elder brother André, who lived to ninety-two, was a prodigy who became one of the twentieth century’s preeminent mathematicians.

In The Weil Conjectures Karen Olsson presents her remarkable subjects as creatures from a fairy tale: “Once there were a brother and sister who devoted themselves to the search for truth. A brother who spent his long life solving problems. A sister who died before she could solve the problem of life.” The sister was Simone Weil (pronounced “vay”), a philosopher and political activist who died in 1943 at age thirty-four and gained fame with the posthumous publication of works, assembled from her voluminous notebooks, on society, justice, and the mystical life of faith. Her elder brother André, who lived to ninety-two, was a prodigy who became one of the twentieth century’s preeminent mathematicians.

more here.

Sadness and Brahms

Alex Ross at The New Yorker:

In the world of Brahms, it is, above all, always late. Light is waning, shadows are growing, silence is encroaching. The topic of lateness and loneliness in Brahms is a familiar one; the adjectives “autumnal” and “elegiac” follow him everywhere. Scholars have tried to parse Brahmsian melancholy in terms biographical, philosophical, and sociopolitical. He was a self-contained man who never married and prized his separateness. He belonged to a generation that saw the irreversible transformation of nature in the age of steam and speed. Reinhold Brinkmann, in his book “Late Idyll,” speaks of Brahms’s consciousness of his latecomer status in musical history, at the end of a line that began with Bach and reached its height with Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert. After him came the deluge of twentieth-century music, of which he got a glimpse in the hotheaded youthful works of Mahler and Richard Strauss.

In the world of Brahms, it is, above all, always late. Light is waning, shadows are growing, silence is encroaching. The topic of lateness and loneliness in Brahms is a familiar one; the adjectives “autumnal” and “elegiac” follow him everywhere. Scholars have tried to parse Brahmsian melancholy in terms biographical, philosophical, and sociopolitical. He was a self-contained man who never married and prized his separateness. He belonged to a generation that saw the irreversible transformation of nature in the age of steam and speed. Reinhold Brinkmann, in his book “Late Idyll,” speaks of Brahms’s consciousness of his latecomer status in musical history, at the end of a line that began with Bach and reached its height with Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert. After him came the deluge of twentieth-century music, of which he got a glimpse in the hotheaded youthful works of Mahler and Richard Strauss.

more here.

In crisis, Trump’s most ardent fans find they love him more

Story Hinckley in The Christian Science Monitor:

To many on the left, President Donald Trump has been a manifest disaster in guiding America through the current pandemic. But Maria Romero most definitely would beg to differ. “The man is not a magician, but he’s doing everything he can. … He believes in America and he believes in Americans,” says Ms. Romero, who lost her job at a car dealership outside of Chicago two weeks ago because of COVID-19. She tunes into President Trump’s coronavirus briefings every evening, saying they make her feel reassured and hopeful. “I could be bitter, I could say, ‘This is President Trump’s fault’ – but it’s not,” she says. “Things were wonderful [before COVID-19]. He did it once, he’ll do it again. I trust him.”

To many on the left, President Donald Trump has been a manifest disaster in guiding America through the current pandemic. But Maria Romero most definitely would beg to differ. “The man is not a magician, but he’s doing everything he can. … He believes in America and he believes in Americans,” says Ms. Romero, who lost her job at a car dealership outside of Chicago two weeks ago because of COVID-19. She tunes into President Trump’s coronavirus briefings every evening, saying they make her feel reassured and hopeful. “I could be bitter, I could say, ‘This is President Trump’s fault’ – but it’s not,” she says. “Things were wonderful [before COVID-19]. He did it once, he’ll do it again. I trust him.”

As the United States navigates a spring season like no other, with much of its population sheltering at home and the economy frozen, President Trump’s core supporters – call them “superfans” – remain staunchly behind a chief executive they believe was Making America Great Again before a pandemic unexpectedly upset his plans. Democrats may maintain that the president initially downplayed the threat from the novel coronavirus. The media may report that the White House failed to prepare for the pandemic by making sure the U.S. had adequate testing and medical supplies. But these superfans, while they agree the crisis has been devastating, believe that President Trump has responded with strong leadership. They think the president is rightly attuned to the need to get the economy moving again as soon as possible, despite warnings from public health experts that broadly reopening workplaces before a vaccine or treatments are available could lead to another spike in fatalities.

More here.

Thursday Poem

To Alexander Fu on His Beginning and 13th Birthday

Cut from your mother, there was a first heartache,

a loneliness before your first peek

at the world, your mother’s hand was a comb

for your proud hair, fresh from the womb—

|born at night, you and moonlight tipped the scale

a 6lb 8oz miracle,

a sky‐kicking son

born to Chinese obligation

but already American.

You were a human flower, a pink carnation.

You were not fed by sunlight and rain.

You sucked the wise milk of Han.

Your first stop, the Riverdale station,

a stuffed lion and meditation.

Out of PS 24, you will become

a full Alexander moon over the trees

|before you’re done. It would not please

your mother to have a moon god for a son.

She would prefer you had the grace

to be mortal, to make the world a better place.

Read more »

Pandemic Story: Failures, Forebodings, Signs of Solidarity

W.T. Whitney in Counterpunch:

The long-term impact of the COVID 19 pandemic, while uncertain, promises to be far-reaching and profound. Here we look for signs evident now that point to various kinds of long-term effects in the future. One set of indicators has to do with U.S. failures in prioritizing and protecting the public’s health. These may provoke movement toward new ways of providing health care, or even of reorganizing society. Signs are evident too of increasing fragility of governance itself, likely to become more apparent as the pandemic’s adverse effects mount. Lastly, markers of human solidarity and of collaboration among nations are on display. Hopefully as regards the people’s cause, they portend durability.

The long-term impact of the COVID 19 pandemic, while uncertain, promises to be far-reaching and profound. Here we look for signs evident now that point to various kinds of long-term effects in the future. One set of indicators has to do with U.S. failures in prioritizing and protecting the public’s health. These may provoke movement toward new ways of providing health care, or even of reorganizing society. Signs are evident too of increasing fragility of governance itself, likely to become more apparent as the pandemic’s adverse effects mount. Lastly, markers of human solidarity and of collaboration among nations are on display. Hopefully as regards the people’s cause, they portend durability.

Public health

Capitalist governments developed public health capabilities aimed, in theory, at putting bio-medical scientific advances in the service of all the people. The object has been to prevent illnesses and guarantee access to curative and rehabilitative care. The assumption long prevailed in the United States that sickness care was be bought and sold, or offered as charity, that is, until the advent of Medicare, Medicaid, and veterans’ health services. Prevention was always the responsibility of government or of private philanthropy. Now privatization and profiteering pervade the U.S. health-care system. Disease prevention, no profit center, has fallen by the wayside. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services in 2019 conducted a six-month long simulation of an influenza epidemic that demonstrated that in the United States 110 million people would be sick and 586,000 would die. It revealed the health system to be “underfunded, underprepared and too disorganized to deal with a global pandemic.” The impact was nil. Under the Trump administration’s 2021 budget, spending on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention dropped by $1.2 billion. People whose job was to plan how to deal with health disasters were dismissed.

More here.

Wednesday, April 15, 2020

‘Amazing’ Math Bridge Extended Beyond Fermat’s Last Theorem

Erica Klarreich in Quanta:

When Andrew Wiles proved Fermat’s Last Theorem in the early 1990s, his proof was hailed as a monumental step forward not just for mathematicians but for all of humanity. The theorem is simplicity itself — it posits that xn + yn = zn has no positive whole-number solutions when n is greater than 2. Yet this simple claim tantalized legions of would-be provers for more than 350 years, ever since the French mathematician Pierre de Fermat jotted it down in 1637 in the margin of a copy of Diophantus’ Arithmetica. Fermat, notoriously, wrote that he had discovered “a truly marvelous proof, which this margin is too narrow to contain.” For centuries, professional mathematicians and amateur enthusiasts sought Fermat’s proof — or any proof at all.

When Andrew Wiles proved Fermat’s Last Theorem in the early 1990s, his proof was hailed as a monumental step forward not just for mathematicians but for all of humanity. The theorem is simplicity itself — it posits that xn + yn = zn has no positive whole-number solutions when n is greater than 2. Yet this simple claim tantalized legions of would-be provers for more than 350 years, ever since the French mathematician Pierre de Fermat jotted it down in 1637 in the margin of a copy of Diophantus’ Arithmetica. Fermat, notoriously, wrote that he had discovered “a truly marvelous proof, which this margin is too narrow to contain.” For centuries, professional mathematicians and amateur enthusiasts sought Fermat’s proof — or any proof at all.

The proof Wiles finally came up with (helped by Richard Taylor) was something Fermat would never have dreamed up. It tackled the theorem indirectly, by means of an enormous bridge that mathematicians had conjectured should exist between two distant continents, so to speak, in the mathematical world. Wiles’ proof of Fermat’s Last Theorem boiled down to establishing this bridge between just two little plots of land on the two continents. The proof, which was full of deep new ideas, set off a cascade of further results about the two sides of this bridge.

More here.

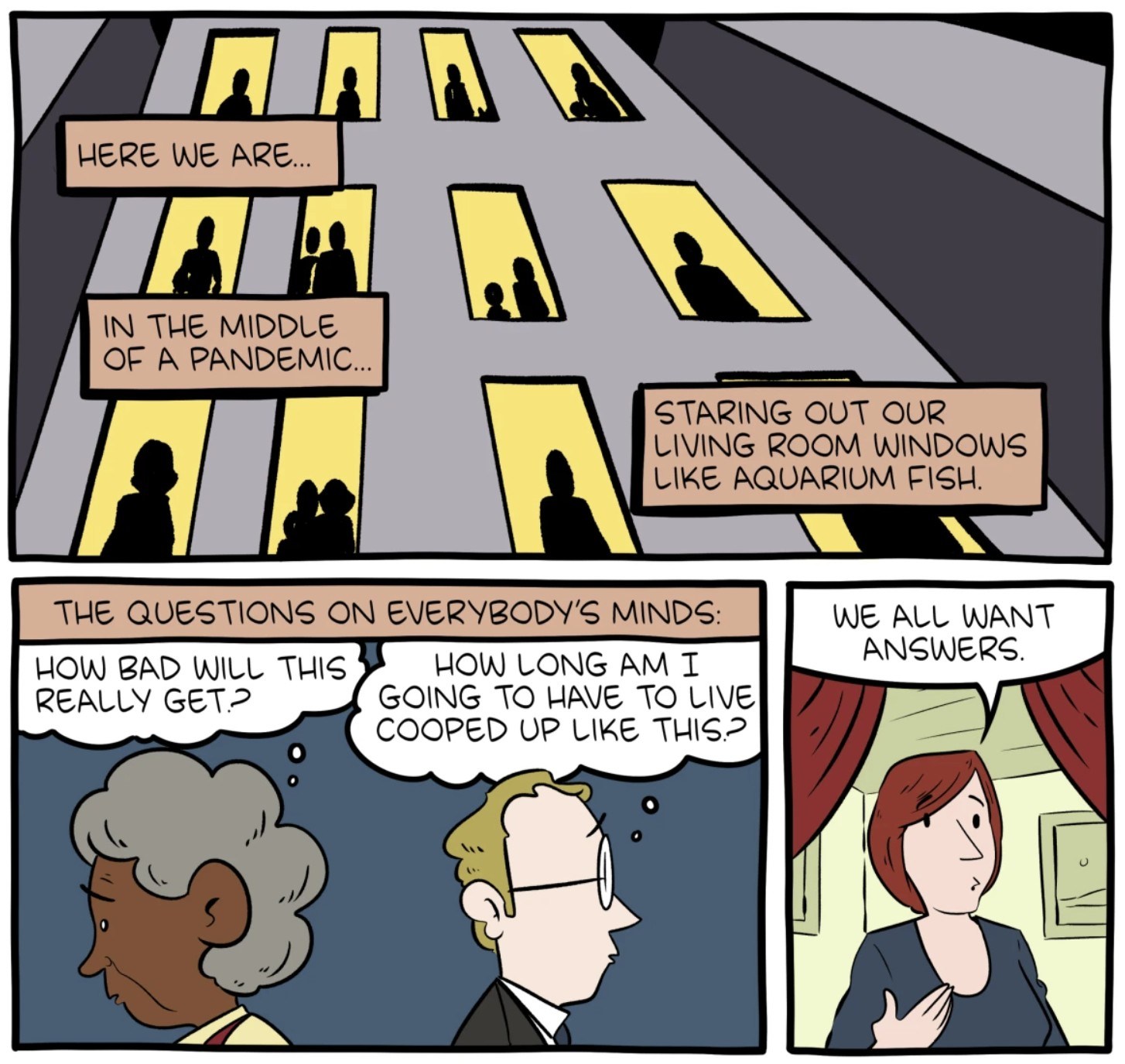

A Comic Strip Tour Of The Wild World Of Pandemic Modeling

Why didn’t Titian leave Venice when he had the chance?

Leanne Ogasawara in The Hedgehog Review:

Given the terrifying nature of the Black Death, it’s hard to understand why Titian didn’t leave Venice in 1576 when he had the chance. He certainly had the means. Fabulously wealthy, he was the most famous artist of his day. Friend of kings and aristocrats, Titian could do whatever Titian wanted. And yet he stayed in his house in the Cannaregio, watching as the skies filled with the acrid smoke of the dead being burned across the lagoon on the dreaded island, Lazzaretto Vecchio, where plague victims were brought to die.

Given the terrifying nature of the Black Death, it’s hard to understand why Titian didn’t leave Venice in 1576 when he had the chance. He certainly had the means. Fabulously wealthy, he was the most famous artist of his day. Friend of kings and aristocrats, Titian could do whatever Titian wanted. And yet he stayed in his house in the Cannaregio, watching as the skies filled with the acrid smoke of the dead being burned across the lagoon on the dreaded island, Lazzaretto Vecchio, where plague victims were brought to die.

Sixteenth-century Venice was like a petri dish. Swampy and unsanitary, conditions in the overcrowded city had always been an invitation to disease. But this was no ordinary sickness. The Black Death struck like lightening, wiping out entire families in days. Bringing agonizing pain, it was often followed by an ignoble death, as disfigured bodies were stripped of their clothing and carted off to be disposed of in mass graves. People prayed and prayed. And those who could, fled to the hills.

The 1576 outbreak in Venice was particularly virulent.

More here.

The Aesthetic

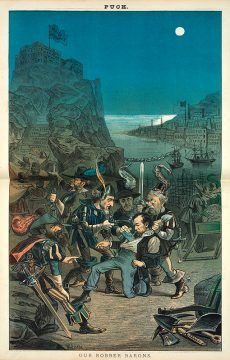

How the Anti-Populists Stopped Bernie Sanders

Thomas Frank at Harper’s Magazine:

“Populism” is the word that comes to the lips of the respectable and the highly educated when they perceive the global system going haywire. Populism is the name they give to the avalanche crashing down on the Alpine wonderland of Davos. Populism is what they call the mutiny that may well turn the supercarrier America into a foundering wreck. Populism, for them, is a one-word evocation of the logic of the mob: it is the people as a great rampaging beast.

“Populism” is the word that comes to the lips of the respectable and the highly educated when they perceive the global system going haywire. Populism is the name they give to the avalanche crashing down on the Alpine wonderland of Davos. Populism is what they call the mutiny that may well turn the supercarrier America into a foundering wreck. Populism, for them, is a one-word evocation of the logic of the mob: it is the people as a great rampaging beast.

What has happened, the thinkers of Beltway and C-suite tell us, is that the common folk have declared independence from the experts and, along the way, from reality itself. And so they the learned must come together to rescue civilization: political scientists, policy wonks, economists, technologists, CEOs, joining as one to save our social order. To save it from populism.

more here.

The Stutterer’s Song: Remembering Bill Withers

Emily Lordi at The Point:

The “I know” is a stutter. It is a stutter that couldn’t be steadier. And the obsessive circularity it winds into the song produces new layers of meaning. In the romantic reading, which is the one on the surface, it only feels like she’s “always gone too long” because that is the nature of love. But it is also possible that the woman really stays away for long stretches at a time—maybe because, like the woman in “Use Me,” she just doesn’t love him that much. Or maybe, thinking ahead to the abusive control Withers expresses on “Who is He (And What is He to You)?”—and, biographically, to the domestic violence that marked his relationship with his first wife, Denise Nicholas—he keeps driving her away. Maybe she leaves to take refuge from him, and the “darkness” he feels in her absence is not only loneliness but guilt. The repeated “I know” opens up alternate meanings, because it is a spiral of knowing that is also not-knowing, or denial. In short, if this is a stutter, it makes the song more articulate; makes it say more, not less.

The “I know” is a stutter. It is a stutter that couldn’t be steadier. And the obsessive circularity it winds into the song produces new layers of meaning. In the romantic reading, which is the one on the surface, it only feels like she’s “always gone too long” because that is the nature of love. But it is also possible that the woman really stays away for long stretches at a time—maybe because, like the woman in “Use Me,” she just doesn’t love him that much. Or maybe, thinking ahead to the abusive control Withers expresses on “Who is He (And What is He to You)?”—and, biographically, to the domestic violence that marked his relationship with his first wife, Denise Nicholas—he keeps driving her away. Maybe she leaves to take refuge from him, and the “darkness” he feels in her absence is not only loneliness but guilt. The repeated “I know” opens up alternate meanings, because it is a spiral of knowing that is also not-knowing, or denial. In short, if this is a stutter, it makes the song more articulate; makes it say more, not less.

more here.

Wednesday Poem

Song of Myself —Excerpt

My foothold is tenon’d and mortis’d in granite,

I laugh at what you call dissolution,

And I know the amplitude of time,

I am the poet of the Body and I am the poet of the Soul,

The pleasures of heaven are with me and the pains of hell

….. are with me,

The first I graft and increase upon myself, the latter I

….. translate into a new tongue.

I am the poet of the woman as same as the man,

And I say it is a great to be a woman as to be a man,

And I say there is nothing greater than the mother of men.

I chant the chant of dilation or pride,

We have had ducking and deprecating about enough,

I show that size is only development.

Have you outstripped the rest? are you the President?

It is a trifle, they will more than arrive there every one, and

….. and still pass on.

I am he that walks with tender and growing night,

I call to the earth and sea half-held by the night.

Press close bare-bosom’d night— press close magnetic

….. nourishing night!

.

Walt Whitman

from Leaves of Grass —Song of Myself

There’s Only One Way to Get the U.S. Back to Work: Testing, Testing and More Testing

Arthur Caplan and Robert Bazell in Time:

The CDC just announced new guidelines for “critical” employees to return to work after possible COVID-19 exposure. Take your temperature often. Wear a mask. Stay 6 ft. away from others when possible. Go home if you feel sick. It is well-intentioned advice. But it is not enough—not for “critical” workers, however defined, or for the rest of us.

Until we have a vaccine, which is likely a year or more off, or truly effective treatments, which may be just as far in the future, the answer is, as it has been since the start of this pandemic: testing, testing and more testing. “Anyone who wants a test can get a test,” President Trump famously proclaimed on March 6. We know how horribly wrong he was. A tragic, preventable combination of errors in the White House, the CDC and FDA kept this country from having tests to detect the new coronavirus as it spread through the population almost unnoticed. By March 6, when Trump insisted America had sufficient testing for all of us, fewer than 2,000 Americans had gotten a test. The testing situation is improving. By April 14, around 3 million Americans had gotten COVID-19 tests, according to the COVID Tracking Project. Tests are becoming easier to access. The Department of Health and Human Services just promulgated rules allowing tests to be administered in pharmacies, and its civil rights division said it would not enforce HIPAA rules to allow more widespread community testing. Gates Ventures is funding a demonstration project that can deliver and pick up testing material for homes in the Seattle area. Abbott Labs won FDA approval for a test that can deliver results in less than 15 minutes.

Bugs that eat plastic

Anne Sverdrup-Thygeson in Delancey Place:

“Every minute enough plastic is dumped into the world’s oceans to fill an entire dump truck. At least as much again ends up in landfill sites, and the amounts are constantly increasing. Because we love plastic. It’s handy and cheap. We produce and use twenty times as much plastic every year now as we did fifty years ago, and less than 10 percent of it is recycled. The rest of the plastic waste ends up in landfills, in roadside ditches, or in the sea. A report issued by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation estimated that if this continues the sea will contain more plastic than fish by 2050. This is because plastic biodegrades extremely slowly in the natural environment. So the discovery that a number of insects can digest and break down plastic is something of a sensation.

“Every minute enough plastic is dumped into the world’s oceans to fill an entire dump truck. At least as much again ends up in landfill sites, and the amounts are constantly increasing. Because we love plastic. It’s handy and cheap. We produce and use twenty times as much plastic every year now as we did fifty years ago, and less than 10 percent of it is recycled. The rest of the plastic waste ends up in landfills, in roadside ditches, or in the sea. A report issued by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation estimated that if this continues the sea will contain more plastic than fish by 2050. This is because plastic biodegrades extremely slowly in the natural environment. So the discovery that a number of insects can digest and break down plastic is something of a sensation.

“Take polystyrene, for example. Even if you don’t think you use it often, I’m guessing that you’ve held some in your hand — if you’ve ever bought takeout food in a carton or a hot drink in anything other than a paper cup. Because polystyrene, also known as isopore, is the material used to make disposable containers for hot food and drink. In the United States alone, 2.5 billion such cups are thrown away every year — and we’re talking about a material that was thought to be nonbiodegradable. Until now. Because it turns out that mealworms consume isopore cups as if they were part of their regular diet.

“In one study, several hundred American and Chinese mealworms were served some isopore. All of them belonged to the darkling beetle species (Tenebrio molitor), which lives outdoors in most parts of the world and sometimes turns up indoors, too, if any soggy flour residue is left lying in your cupboards for too long. They gobbled up the isopore at record speed, and the larvae raised on this peculiar diet pupated and hatched into adult beetles as normal. Within a month, for example, five hundred Chinese mealworms had gobbled up a third of the 5.8 grams of isopore served up to them. All that was left was some carbon dioxide and a spot of beetle poo, which was apparently pure enough to use as planting soil. There was no difference between the survival rates of larvae that received normal food and those on the isopore diet.

More here.

Ezra Klein: I’ve read the plans to reopen the economy and They’re scary

Ezra Klein in Vox:

Over the past few days, I’ve been reading the major plans for what comes after social distancing. You can read them, too. There’s one from the right-leaning American Enterprise Institute, the left-leaning Center for American Progress, Harvard University’s Safra Center for Ethics, and Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Romer.

Over the past few days, I’ve been reading the major plans for what comes after social distancing. You can read them, too. There’s one from the right-leaning American Enterprise Institute, the left-leaning Center for American Progress, Harvard University’s Safra Center for Ethics, and Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Romer.

I thought, perhaps naively, that reading them would be a comfort — at least then I’d be able to imagine the path back to normal. But it wasn’t. In different ways, all these plans say the same thing: Even if you can imagine the herculean political, social, and economic changes necessary to manage our way through this crisis effectively, there is no normal for the foreseeable future. Until there’s a vaccine, the United States either needs economically ruinous levels of social distancing, a digital surveillance state of shocking size and scope, or a mass testing apparatus of even more shocking size and intrusiveness.

More here.

Tuesday, April 14, 2020

What the world can learn from Kerala about how to fight covid-19

Sonia Faleiro in MIT Technology Review:

The sun had already set on March 7 when Nooh Pullichalil Bava received the call. “I have bad news,” his boss warned. On February 29, a family of three had arrived in the Indian state of Kerala from Italy, where they lived. The trio skipped a voluntary screening for covid-19 at the airport and took a taxi 125 miles (200 kilometers) to their home in the town of Ranni. When they started developing symptoms soon afterward, they didn’t alert the hospital. Now, a whole week after taking off from Venice, all three—a middle-aged man and woman and their adult son—had tested positive for the virus, and so had two of their elderly relatives.

PB Nooh, as he is known, is the civil servant in charge of the district of Pathanamthitta, where Ranni is located; his boss is the state health secretary. He’d been expecting a call like this for days. Kerala has a long history of migration and a constant flow of international travelers, and the new coronavirus was spreading everywhere. The first Indian to test positive for covid-19 was a medical student who had arrived in Kerala from Wuhan, China, at the end of January. At 11:30 that same night, Nooh joined his boss and a team of government doctors on a video call to map out a strategy.

More here.

Russian Experiments In Life After Death

Sophie Pinkham at The Nation:

Fedorov’s ambition was not limited to those still living. He imagined resurrecting every person who had ever lived. Inverting the idea of the duty of the living to future generations, he argued that we owe a “resurrectory debt” to our parents, and he insisted that as technology advanced, we would pay off this debt by piecing our families back together from bones and even specks of dust. (A crackpot visionary rather than a scientist, he was short on specifics about how we might do this.) To solve the problem of housing the vast resurrected population, he looked to space, proposing the colonization of the galaxy—a hope shared by people like Thiel and Elon Musk today. But Fedorov imagined the work and benefits of immortality as collective and universal. He accumulated a number of followers during his lifetime and after his death, and his reputation as an eccentric visionary endures in Russia.

Fedorov’s ambition was not limited to those still living. He imagined resurrecting every person who had ever lived. Inverting the idea of the duty of the living to future generations, he argued that we owe a “resurrectory debt” to our parents, and he insisted that as technology advanced, we would pay off this debt by piecing our families back together from bones and even specks of dust. (A crackpot visionary rather than a scientist, he was short on specifics about how we might do this.) To solve the problem of housing the vast resurrected population, he looked to space, proposing the colonization of the galaxy—a hope shared by people like Thiel and Elon Musk today. But Fedorov imagined the work and benefits of immortality as collective and universal. He accumulated a number of followers during his lifetime and after his death, and his reputation as an eccentric visionary endures in Russia.

more here.