Susan Sidlauskas at nonsite:

Nearly two decades ago, photo historian Douglas Nickel observed that traditional art history had not yet developed the tools for handling non-art photographs.1 In many ways, much progress has been made since 2001: vernacular photographs of every kind have become worthy objects of study for scholars and critics—not only within visual culture, but in history, sociology, anthropology, and literary and cultural studies. In fact, these days, as Nickel himself has pointed out, studies of vernacular photographs outpace the production of monographic books about “fine art photographers.”2

Nearly two decades ago, photo historian Douglas Nickel observed that traditional art history had not yet developed the tools for handling non-art photographs.1 In many ways, much progress has been made since 2001: vernacular photographs of every kind have become worthy objects of study for scholars and critics—not only within visual culture, but in history, sociology, anthropology, and literary and cultural studies. In fact, these days, as Nickel himself has pointed out, studies of vernacular photographs outpace the production of monographic books about “fine art photographers.”2

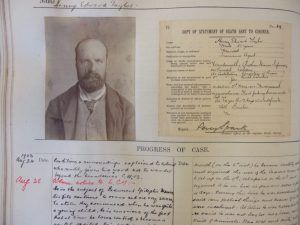

However, it remains difficult for art historians to build an interpretative model that takes full measure of the visual subtleties of non-art photographs—including their unexpected aspirations towards the aesthetic—without slighting the historical and social conditions in which they were produced.3 With that challenge in mind, I consider here those very aspirations, as they surface repeatedly in a group of “medical portraits”: casebook photographs of patients made between 1885 and 1916 at the Holloway Sanatorium in St. Ann’s Heath, Virginia Water, Surrey, England (fig. 1).

more here.