Tomas Pueyo in Medium:

A month ago we sounded the alarm with Coronavirus: Why You Must Act Now. After that, we asked countries to buy us time with Coronavirus: The Hammer and the Dance and looked in detail at the US situation with Coronavirus: Out of Many, One. Together, these articles have been viewed by over 60 million people and translated into over 40 languages.

A month ago we sounded the alarm with Coronavirus: Why You Must Act Now. After that, we asked countries to buy us time with Coronavirus: The Hammer and the Dance and looked in detail at the US situation with Coronavirus: Out of Many, One. Together, these articles have been viewed by over 60 million people and translated into over 40 languages.

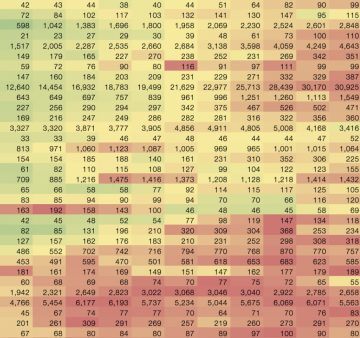

Since then, the number of confirmed coronavirus cases has grown twentyfold, from 125,000 to over 2.5 million. Billions of people around the world are under the Hammer: Their governments have implemented heavy social distancing measures to quench the spread of the virus.

Most did the right thing: The Hammer was the right decision. It bought us time to reduce the epidemic and to figure out what to do during the next phase, the Dance, in which we relax the harsh social distancing measures in a careful way to avoid a second outbreak. But the Hammer is hard. Millions have lost their jobs, their income, their savings, their businesses, their freedom. The world needs answers: When is this over? When do we relax these measures and go back to the new normal? What will it take? What will life be like?

When do we get to dance?

This article will explain when, and how, we will dance.

More here.

Eating garlic, taking a bath, and drinking hot water. These are three alleged “cures” that will not protect you from the coronavirus, but they have become so widely believed that the World Health Organization has launched a

Eating garlic, taking a bath, and drinking hot water. These are three alleged “cures” that will not protect you from the coronavirus, but they have become so widely believed that the World Health Organization has launched a  In a freezing December day in 1386, at an old priory in Paris that today is a museum of science and technology—a temple of human reason—an eager crowd of thousands gathered to watch two knights fight a duel to the death with lance and sword and dagger. A beautiful young noblewoman, dressed all in black and exposed to the crowd’s stares, anxiously awaited the outcome. The trial by combat would decide whether she had told the truth—and thus whether she would live or die. Like today, sexual assault and rape often went unpunished and even unreported in the Middle Ages. But a public accusation of rape, at the time a capital offense and often a cause for scandalous rumors endangering the honor of those involved, could have grave consequences for both accuser and accused, especially among the nobility.

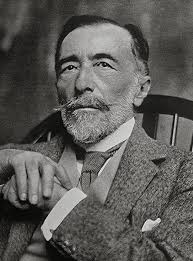

In a freezing December day in 1386, at an old priory in Paris that today is a museum of science and technology—a temple of human reason—an eager crowd of thousands gathered to watch two knights fight a duel to the death with lance and sword and dagger. A beautiful young noblewoman, dressed all in black and exposed to the crowd’s stares, anxiously awaited the outcome. The trial by combat would decide whether she had told the truth—and thus whether she would live or die. Like today, sexual assault and rape often went unpunished and even unreported in the Middle Ages. But a public accusation of rape, at the time a capital offense and often a cause for scandalous rumors endangering the honor of those involved, could have grave consequences for both accuser and accused, especially among the nobility. It is historically unsurprising that, in the context of an emerging mass culture, nostalgia for older forms should express itself in their revival and imitation as high-art products. The adventure story was promoted into literature. A taste for this ‘canon’, from Stevenson to Kipling, from gaucho stories to Westerns, was formative for Borges, whose admiration for Conrad was well known. It is a mistake to consider Borges a modernist; rather, when he was awarded the Prix Formentor in 1961, marking his belated arrival on the world literary stage (along with Beckett, who shared the prize that year), it was a harbinger of the postmodern return to plot, to intricacy and intrigue, and away from the densities of poetic language. Conrad’s ‘postmodern’ reversion to plot was, however, combined with a different kind of modernist supplement, namely the work of style. Conrad dealt with his traditional raw material according to a stylistic strategy very different from Borges’s superposition of alternating plots and narrative paradoxes; yet the affinity betrays a deeper contradiction in the literary production process common to their respective historical moments.

It is historically unsurprising that, in the context of an emerging mass culture, nostalgia for older forms should express itself in their revival and imitation as high-art products. The adventure story was promoted into literature. A taste for this ‘canon’, from Stevenson to Kipling, from gaucho stories to Westerns, was formative for Borges, whose admiration for Conrad was well known. It is a mistake to consider Borges a modernist; rather, when he was awarded the Prix Formentor in 1961, marking his belated arrival on the world literary stage (along with Beckett, who shared the prize that year), it was a harbinger of the postmodern return to plot, to intricacy and intrigue, and away from the densities of poetic language. Conrad’s ‘postmodern’ reversion to plot was, however, combined with a different kind of modernist supplement, namely the work of style. Conrad dealt with his traditional raw material according to a stylistic strategy very different from Borges’s superposition of alternating plots and narrative paradoxes; yet the affinity betrays a deeper contradiction in the literary production process common to their respective historical moments. Covid 19 is a challenge to which we are all seeking to respond. Some major social upheavals lead to fundamental and progressive shifts, think for example of the way the AIDS crisis accelerated the fight for LGBT rights; while others, most obviously the global financial meltdown of 2008, fail to precipitate major reform despite causing immense hardship. Indeed, the widespread assumption on the left that the financial crisis would lead to a reaction against inequality and global finance was not only disappointed but confounded as the political momentum was, in many countries, seized by nationalist populism.

Covid 19 is a challenge to which we are all seeking to respond. Some major social upheavals lead to fundamental and progressive shifts, think for example of the way the AIDS crisis accelerated the fight for LGBT rights; while others, most obviously the global financial meltdown of 2008, fail to precipitate major reform despite causing immense hardship. Indeed, the widespread assumption on the left that the financial crisis would lead to a reaction against inequality and global finance was not only disappointed but confounded as the political momentum was, in many countries, seized by nationalist populism. Mark Denison began hunting for a drug to treat COVID-19 almost a decade before the contagion, driven by a novel coronavirus, devastated the world this year. Denison is not a prophet, but he is a virologist and an expert on the often deadly coronavirus family, members of which also caused the SARS outbreak in 2002 and the MERS eruption in 2012. It is a big viral group, and “we were pretty certain another one would soon emerge,” says Denison, who directs the division of pediatric infectious diseases at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

Mark Denison began hunting for a drug to treat COVID-19 almost a decade before the contagion, driven by a novel coronavirus, devastated the world this year. Denison is not a prophet, but he is a virologist and an expert on the often deadly coronavirus family, members of which also caused the SARS outbreak in 2002 and the MERS eruption in 2012. It is a big viral group, and “we were pretty certain another one would soon emerge,” says Denison, who directs the division of pediatric infectious diseases at Vanderbilt University Medical Center. In the early nineties, the economist Jeffrey Sachs was known as a “shock therapist,” for advising the Soviet Union on its controversial transition to a free-market economy. Since then, Sachs has shifted his focus to poverty alleviation and international development, becoming one of the most visible academics in the world. His book “

In the early nineties, the economist Jeffrey Sachs was known as a “shock therapist,” for advising the Soviet Union on its controversial transition to a free-market economy. Since then, Sachs has shifted his focus to poverty alleviation and international development, becoming one of the most visible academics in the world. His book “ Scott Newstok’s new book,

Scott Newstok’s new book,  José Ortega y Gasset is a largely forgotten 20th century thinker, an unconventional Spanish philosopher whose most important social science work,

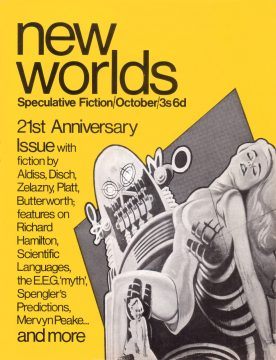

José Ortega y Gasset is a largely forgotten 20th century thinker, an unconventional Spanish philosopher whose most important social science work,  No doubt Ballard and Pevsner make strange bedfellows, but if we accept—and I think we can—that Pevsner’s charge of “outrageous stimulation” was a localized condemnation of broader tendencies, then there is a connection. For the diagnosis of “outrageous stimulation” was one that Ballard, in a strong sense, shared, although the consequences he drew were radically different. As he wrote in a later reflection: “A unique collision of private and public fantasy took place in the 1960s. … The public dream of Hollywood for the first time merged with the private imagination of the hyper-stimulated 60s TV viewer.” However for Ballard, the outcome of this was not some sort of constant escalation of experience—on the contrary “its finish line,” he wrote, “was that death of affect, the lack of feeling, which seemed inseparable from the communications landscape.” Whereas Pevsner’s demand on the cusp of the 1960s was to rein in the new license and reassert prior controls, Ballard’s suggestion was instead to embrace existing conditions and pursue their possibilities. “Given the unlimited opportunities which the media landscape now offers to the wayward imagination,” he wrote, “I feel we should immerse ourselves in the most destructive element, ourselves, and swim.” The best we can hope for of the twentieth century, he continued, is “the attainment of a moral and just psychopathology.”

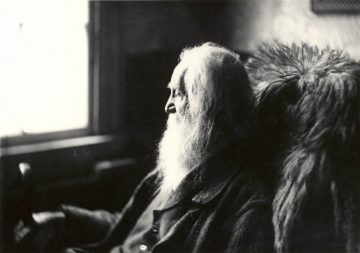

No doubt Ballard and Pevsner make strange bedfellows, but if we accept—and I think we can—that Pevsner’s charge of “outrageous stimulation” was a localized condemnation of broader tendencies, then there is a connection. For the diagnosis of “outrageous stimulation” was one that Ballard, in a strong sense, shared, although the consequences he drew were radically different. As he wrote in a later reflection: “A unique collision of private and public fantasy took place in the 1960s. … The public dream of Hollywood for the first time merged with the private imagination of the hyper-stimulated 60s TV viewer.” However for Ballard, the outcome of this was not some sort of constant escalation of experience—on the contrary “its finish line,” he wrote, “was that death of affect, the lack of feeling, which seemed inseparable from the communications landscape.” Whereas Pevsner’s demand on the cusp of the 1960s was to rein in the new license and reassert prior controls, Ballard’s suggestion was instead to embrace existing conditions and pursue their possibilities. “Given the unlimited opportunities which the media landscape now offers to the wayward imagination,” he wrote, “I feel we should immerse ourselves in the most destructive element, ourselves, and swim.” The best we can hope for of the twentieth century, he continued, is “the attainment of a moral and just psychopathology.” There are poets who find their strength in brevity, who use as few words as possible, arranged in the minimum number of lines, to evoke sense perception, emotion, and idea. Walt Whitman, it goes without saying, is not one of those. He is most comfortable on a broader scale. His great poems—“Song of Myself,” “The Sleepers,” “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry,” “Out of the Cradle Endlessly Rocking,” and “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloomed”—straddle hundreds of lines, providing the poet with room to catalogue particulars (The glories strung like beads on my smallest sights and hearings, he calls them), to stack up parallel statements, to address his reader, to depart from and return to his argument, and to construct a kind of poetic architecture designed to be mimetic of the process of thinking, and thus draw us more intimately near. This is why his shorter poems often feel like parts of a larger, more encompassing one; even satisfyingly complete shorter pieces such as “To You” and “This Compost” might be seen as outtakes, or gestures in the direction of some overarching intention.

There are poets who find their strength in brevity, who use as few words as possible, arranged in the minimum number of lines, to evoke sense perception, emotion, and idea. Walt Whitman, it goes without saying, is not one of those. He is most comfortable on a broader scale. His great poems—“Song of Myself,” “The Sleepers,” “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry,” “Out of the Cradle Endlessly Rocking,” and “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloomed”—straddle hundreds of lines, providing the poet with room to catalogue particulars (The glories strung like beads on my smallest sights and hearings, he calls them), to stack up parallel statements, to address his reader, to depart from and return to his argument, and to construct a kind of poetic architecture designed to be mimetic of the process of thinking, and thus draw us more intimately near. This is why his shorter poems often feel like parts of a larger, more encompassing one; even satisfyingly complete shorter pieces such as “To You” and “This Compost” might be seen as outtakes, or gestures in the direction of some overarching intention. Nassim Nicholas Taleb is “irritated,” he told Bloomberg Television on March 31st, whenever the

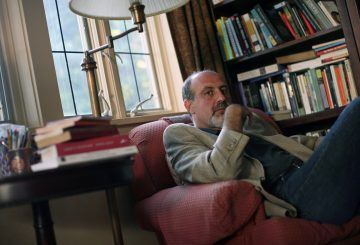

Nassim Nicholas Taleb is “irritated,” he told Bloomberg Television on March 31st, whenever the  When a young girl came to New York University (NYU) Langone Health for a routine follow-up, tests seemed to show that the medulloblastoma for which she had been treated a few years earlier had returned. The girl’s recurrent cancer was found in the same part of brain as before, and the biopsy seemed to confirm medulloblastoma. With this diagnosis, the girl would begin a specific course of radiotherapy and chemotherapy. But just as neuropathologist Matija Snuderl was about to sign off on the diagnosis and set her on that treatment path, he hesitated. The biopsy was slightly unusual, he thought, and he remembered a previous case in which what was thought to be medulloblastoma turned out to be something else. So, to help him make up his mind, Snuderl turned to a computer.

When a young girl came to New York University (NYU) Langone Health for a routine follow-up, tests seemed to show that the medulloblastoma for which she had been treated a few years earlier had returned. The girl’s recurrent cancer was found in the same part of brain as before, and the biopsy seemed to confirm medulloblastoma. With this diagnosis, the girl would begin a specific course of radiotherapy and chemotherapy. But just as neuropathologist Matija Snuderl was about to sign off on the diagnosis and set her on that treatment path, he hesitated. The biopsy was slightly unusual, he thought, and he remembered a previous case in which what was thought to be medulloblastoma turned out to be something else. So, to help him make up his mind, Snuderl turned to a computer. When the virus

When the virus