The Mostly Everything That Everyone Is

—for BIH

My younger brother, a dutiful brave person, spends his work life studying

………. the chestnut fungus Cryphonectria parasitica so American chestnut trees

………. will not entirely vanish;

i’m especially glad for his work when i’m trying to get the skins off the brain-

………. shaped nuts with their curly, dented integuments.

He was the cheerful child in the family, less seized than his siblings by the idea

………. that to please our parents even somewhat we had to be almost or

………. completely perfect at each task.

It seems his studied fungus makes cankers of two types: either they swell or sink.

………. If sinking cankers, the wound kills the tree; it “knows” at its wound level

………. what a life force is. Some genes that hurt the fungus help the tree. If the tree

………. dies, the disease has become visible or it is visible because it dies.

Most of life’s processes are repeatable—at first i wrote “all of life’s” but that’s so

………. not true. Nerve-like structures fall from clouds only once. A shorter dawn

………. sets in before the main dawn. Millions rise & go faithfully to work,

………. taking their resolve, each person clears one throat, music is note by note,

my brother gets our elderly mother up, others in his family rise, he goes to his job

………. free of self pity, the suppressed cheer of his childhood transferred

to his lab mates who monitor the tiny lives growing without human stress, hate,

………. intention or cruelty but also without artful song so they dazzle no one.

My brother and i are as close as the skin on a chestnut is to the chestnut, as close

………. as bark of the tree to its uses. When our mother was sad she shut herself

………. in her room, & when she felt better she’d come out. You have to slough

………. some things off, she’d say, loving us with decades of feral intensity.

He goes along, days pass through the mostly everything that everyone is, a sense

………. of continuance is pulled from nothing, something produced when it can’t

………. stand being nothing, love in the experiments, numbers in the mystery,

………. the healing of the wound, Psyche sorting seeds like minutes, a wound

………. clinging to the tree, sometimes its fruit is food, sometimes the tree

………. is nearly perfectly waiting

by Brenda Hillman

from Emergence Magazine

Amartya Sen in The Indian Express:

Amartya Sen in The Indian Express: For decades, Haruki Murakami defined contemporary Japanese literature for the Anglophone reader. In such bona fide masterpieces as “The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle” and “A Wild Sheep Chase,” the author created a surreal world of talking sheep and lost cats, jazz bars and manic pixie dream girls.

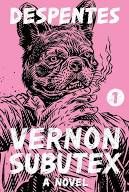

For decades, Haruki Murakami defined contemporary Japanese literature for the Anglophone reader. In such bona fide masterpieces as “The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle” and “A Wild Sheep Chase,” the author created a surreal world of talking sheep and lost cats, jazz bars and manic pixie dream girls. Underlying all of Despentes’s work is the concept of rape. It is the omnipresent possibility through which everything is refracted. There’s a war going on, her books insist, not so much between men and women as on men and women, waged through the constructs of gender. Masculinity, for Despentes, is the artillery that tears our bodies apart, while femininity is the drug of mass indoctrination. What she had learned from punk rock, she once said, was to look clearly at the world and declare it rotten.

Underlying all of Despentes’s work is the concept of rape. It is the omnipresent possibility through which everything is refracted. There’s a war going on, her books insist, not so much between men and women as on men and women, waged through the constructs of gender. Masculinity, for Despentes, is the artillery that tears our bodies apart, while femininity is the drug of mass indoctrination. What she had learned from punk rock, she once said, was to look clearly at the world and declare it rotten. MY TWIN BROTHER IS A DOCTOR

MY TWIN BROTHER IS A DOCTOR There has never been an American president as spiritually impoverished as Donald Trump. And his spiritual poverty, like an overdrawn checking account that keeps imposing new penalties on a customer already in difficult straits, is draining the last reserves of decency among us at a time when we need it most. I do not mean that Trump is the least religious among our presidents, though I have no doubt that he is;

There has never been an American president as spiritually impoverished as Donald Trump. And his spiritual poverty, like an overdrawn checking account that keeps imposing new penalties on a customer already in difficult straits, is draining the last reserves of decency among us at a time when we need it most. I do not mean that Trump is the least religious among our presidents, though I have no doubt that he is;  As the coronavirus lockdown began, the first impulse was to search for historical analogies—1914, 1929, 1941? As the weeks have ground on, what has come ever more to the fore is the historical novelty of the shock that we are living through. As a result of the coronavirus pandemic, America’s economy is now widely expected to shrink by a quarter. That is as much as during the Great Depression. But whereas the contraction after 1929 stretched over a four-year period, the coronavirus implosion will happen over the next three months. There has never been a crash landing like this before. There is something new under the sun. And it is horrifying.

As the coronavirus lockdown began, the first impulse was to search for historical analogies—1914, 1929, 1941? As the weeks have ground on, what has come ever more to the fore is the historical novelty of the shock that we are living through. As a result of the coronavirus pandemic, America’s economy is now widely expected to shrink by a quarter. That is as much as during the Great Depression. But whereas the contraction after 1929 stretched over a four-year period, the coronavirus implosion will happen over the next three months. There has never been a crash landing like this before. There is something new under the sun. And it is horrifying. Nature is mighty, and scary, and we have not defeated it but live within it, subject to its temperamental power, no matter where it is that you live or how protected you may normally feel. As the coronavirus has paralyzed much of the northern hemisphere, for instance,

Nature is mighty, and scary, and we have not defeated it but live within it, subject to its temperamental power, no matter where it is that you live or how protected you may normally feel. As the coronavirus has paralyzed much of the northern hemisphere, for instance,  And then I read The Omni-Americans, Murray’s first book, originally published in 1970 and now reissued in a fiftieth-anniversary edition by the Library of America. It would be difficult to overstate the impact that this essay collection, especially the title essay, had on my life. The Omni-Americans made it clear that American blacks and whites (and Americans of Asian, Native, and Latinx descent, too) are unlike people anywhere else in that they have, however little any number of them may want to admit it, comingled, both physically and culturally, to the extent that the nation is, in Murray’s words, “incontestably mulatto.” Black culture is of course a central part of this mix, and what I took from the book was that there was no place in America a black person could go—even if there were places that person wouldn’t particularly want to go—and not still be among his or her or their own.

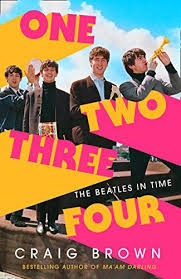

And then I read The Omni-Americans, Murray’s first book, originally published in 1970 and now reissued in a fiftieth-anniversary edition by the Library of America. It would be difficult to overstate the impact that this essay collection, especially the title essay, had on my life. The Omni-Americans made it clear that American blacks and whites (and Americans of Asian, Native, and Latinx descent, too) are unlike people anywhere else in that they have, however little any number of them may want to admit it, comingled, both physically and culturally, to the extent that the nation is, in Murray’s words, “incontestably mulatto.” Black culture is of course a central part of this mix, and what I took from the book was that there was no place in America a black person could go—even if there were places that person wouldn’t particularly want to go—and not still be among his or her or their own. If a German raid had not compelled Jim McCartney and Mary Mohin to get to know each other better, would Paul McCartney have been born? If Paul had passed his Latin O level, he wouldn’t have stayed down a year, befriended George Harrison and introduced him to John Lennon. Would any of us be the same if Ringo had never emerged from a ten-week coma as a child, or if his grandmother hadn’t then forced him to write with his right hand instead of naturally with his left, which gave his drumming ‘the idiosyncratic style that countless Beatles tribute acts still find hard to duplicate’? When Lennon beats up Bob Wooler, MC at the Cavern, for calling him a ‘bloody queer’, Brown provides fourteen differing accounts of what happened, four from Lennon himself. A similar chorus speculates on whether Lennon and Brian Epstein had sex, with Brown again providing differing accounts from Lennon, and Yoko adding that she thought John fancied Paul.

If a German raid had not compelled Jim McCartney and Mary Mohin to get to know each other better, would Paul McCartney have been born? If Paul had passed his Latin O level, he wouldn’t have stayed down a year, befriended George Harrison and introduced him to John Lennon. Would any of us be the same if Ringo had never emerged from a ten-week coma as a child, or if his grandmother hadn’t then forced him to write with his right hand instead of naturally with his left, which gave his drumming ‘the idiosyncratic style that countless Beatles tribute acts still find hard to duplicate’? When Lennon beats up Bob Wooler, MC at the Cavern, for calling him a ‘bloody queer’, Brown provides fourteen differing accounts of what happened, four from Lennon himself. A similar chorus speculates on whether Lennon and Brian Epstein had sex, with Brown again providing differing accounts from Lennon, and Yoko adding that she thought John fancied Paul. MIRACLE CURES,

MIRACLE CURES, Can we leap beyond flattening the curve and eliminate COVID-19 as a public health threat—not years from now but weeks? “It’s a war we should fight to win,” declared Harvey V. Fineberg, former Dean of the Harvard School of Public Health, in the New England Journal of Medicine.1 War metaphors applied to health—“War on Drugs,” “War on Cancer”—are tiresome and often counterproductive. But considering the attempt to overcome COVID-19, the metaphor could not be more apt. Hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions, of lives are at risk. The economy of much of the world depends on the outcome. If it’s improperly managed, the effort to contain the pandemic could drag on for months or years longer than necessary. As in all wars, the battles are complex, varied and ever-changing. High priority must go to health care workers to get them personal protective equipment, ventilators, and all the tools they need. Efforts to develop effective treatments and a protective vaccine must proceed with maximum haste.

Can we leap beyond flattening the curve and eliminate COVID-19 as a public health threat—not years from now but weeks? “It’s a war we should fight to win,” declared Harvey V. Fineberg, former Dean of the Harvard School of Public Health, in the New England Journal of Medicine.1 War metaphors applied to health—“War on Drugs,” “War on Cancer”—are tiresome and often counterproductive. But considering the attempt to overcome COVID-19, the metaphor could not be more apt. Hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions, of lives are at risk. The economy of much of the world depends on the outcome. If it’s improperly managed, the effort to contain the pandemic could drag on for months or years longer than necessary. As in all wars, the battles are complex, varied and ever-changing. High priority must go to health care workers to get them personal protective equipment, ventilators, and all the tools they need. Efforts to develop effective treatments and a protective vaccine must proceed with maximum haste. A doughnut cooked up in Oxford will guide Amsterdam out of the economic mess left by the coronavirus pandemic.

A doughnut cooked up in Oxford will guide Amsterdam out of the economic mess left by the coronavirus pandemic.