Siddhartha Mukherjee in The New Yorker:

At 4:18 a.m. on February 1, 1997, a fire broke out in the Aisin Seiki company’s Factory No. 1, in Kariya, a hundred and sixty miles southwest of Tokyo. Soon, flames had engulfed the plant and incinerated the production line that made a part called a P-valve—a device used in vehicles to modulate brake pressure and prevent skidding. The valve was small and cheap—about the size of a fist, and roughly ten dollars apiece—but indispensable. The Aisin factory normally produced almost thirty-three thousand valves a day, and was, at the time, the exclusive supplier of the part for the Toyota Motor Corporation. Within hours, the magnitude of the loss was evident to Toyota. The company had adopted “just in time” (J.I.T.) production: parts, such as P-valves, were produced according to immediate needs—to precisely match the number of vehicles ready for assembly—rather than sitting around in stockpiles. But the fire had now put the whole enterprise at risk: with no inventory in the warehouse, there were only enough valves to last a single day. The production of all Toyota vehicles was about to grind to a halt. “Such is the fragility of JIT: a surprise event can paralyze entire networks and even industries,” the management scholars Toshihiro Nishiguchi and Alexandre Beaudet observed the following year, in a case study of the episode.

At 4:18 a.m. on February 1, 1997, a fire broke out in the Aisin Seiki company’s Factory No. 1, in Kariya, a hundred and sixty miles southwest of Tokyo. Soon, flames had engulfed the plant and incinerated the production line that made a part called a P-valve—a device used in vehicles to modulate brake pressure and prevent skidding. The valve was small and cheap—about the size of a fist, and roughly ten dollars apiece—but indispensable. The Aisin factory normally produced almost thirty-three thousand valves a day, and was, at the time, the exclusive supplier of the part for the Toyota Motor Corporation. Within hours, the magnitude of the loss was evident to Toyota. The company had adopted “just in time” (J.I.T.) production: parts, such as P-valves, were produced according to immediate needs—to precisely match the number of vehicles ready for assembly—rather than sitting around in stockpiles. But the fire had now put the whole enterprise at risk: with no inventory in the warehouse, there were only enough valves to last a single day. The production of all Toyota vehicles was about to grind to a halt. “Such is the fragility of JIT: a surprise event can paralyze entire networks and even industries,” the management scholars Toshihiro Nishiguchi and Alexandre Beaudet observed the following year, in a case study of the episode.

Toyota’s response was extraordinary: by six-thirty that morning, while the factory was still smoldering, executives huddled to organize the production of P-valves at other factories. It was a “war room,” one official recalled. The next day, a Sunday, small and large factories, some with no direct connection to Toyota, or even to the automotive industry, received detailed instructions for manufacturing the P-valves. By February 4th, three days after the fire, many of these factories had repurposed their machines to make the valves. Brother Industries, a Japanese company best known for its sewing machines and typewriters, adapted a computerized milling device that made typewriter parts to start making P-valves. The ad-hoc work-around was inefficient—it took fifteen minutes to complete each valve, its general manager admitted—but the country’s largest company was in trouble, and so the crisis had become a test of national solidarity. All in all, Toyota lost some seventy thousand vehicles—an astonishingly small number, given the millions of orders it fulfilled that year. By the end of the week, it had increased shifts and lengthened hours. Within the month, the company had rebounded.

Every enterprise learns its strengths and weaknesses from an Aisin-fire moment—from a disaster that spirals out of control. What those of us in the medical profession have learned from the covid-19 crisis has been dismaying, and on several fronts. Medicine isn’t a doctor with a black bag, after all; it’s a complex web of systems and processes. It is a health-care delivery system—providing antibiotics to a child with strep throat or a new kidney to a patient with renal failure. It is a research program, guiding discoveries from the lab bench to the bedside. It is a set of protocols for quality control—from clinical-practice guidelines to drug and device approvals. And it is a forum for exchanging information, allowing for continuous improvement in patient care. In each arena, the pandemic has revealed some strengths—including frank heroism and ingenuity—but it has also exposed hidden fractures, silent aneurysms, points of fragility. Systems that we thought were homeostatic—self-regulating, self-correcting, like a human body in good health—turned out to be exquisitely sensitive to turbulence, like the body during critical illness. Everyone now asks: When will things get back to normal? But, as a physician and researcher, I fear that the resumption of normality would signal a failure to learn. We need to think not about resumption but about revision.

More here.

When major decisions must be made amid high scientific uncertainty, as is the case with Covid-19, we can’t afford to silence or demonize professional colleagues with heterodox views. Even worse, we can’t allow questions of science, medicine, and public health to become captives of tribalized politics. Today, more than ever, we need vigorous academic debate.

When major decisions must be made amid high scientific uncertainty, as is the case with Covid-19, we can’t afford to silence or demonize professional colleagues with heterodox views. Even worse, we can’t allow questions of science, medicine, and public health to become captives of tribalized politics. Today, more than ever, we need vigorous academic debate.

It reveals Jung’s certainty about the going down of the West: a culture and a civilization which even in 1961 had profoundly run out of any gyring or generative energy and was already quite still, poised at the point of stasis before the inevitable unwinding begins. From this, a vision unfolds of western culture as seen from the perspective of the dead: of the joining from past to future that an unbroken chain of linkages ensures, followed by the horrifying awareness of how we have lost our linkage to the primordial past—leaving us an age adrift, nowhere, bereft. The only possible response to such seeing is to lament; to turn to face our ancestors; to bury optimism as a kind of dereliction of our duty; and to learn to dance for the dead. I cannot stress starkly enough the sheer physicality of reading this book, the pain it draws forth, and not only from enduring for eight hundred pages what is unbearable to consider. There is a deeper mystery afoot and it would appear that, in the presence of words truly uttered and written, one virtually has to die to keep up one’s end of the arrangement.

It reveals Jung’s certainty about the going down of the West: a culture and a civilization which even in 1961 had profoundly run out of any gyring or generative energy and was already quite still, poised at the point of stasis before the inevitable unwinding begins. From this, a vision unfolds of western culture as seen from the perspective of the dead: of the joining from past to future that an unbroken chain of linkages ensures, followed by the horrifying awareness of how we have lost our linkage to the primordial past—leaving us an age adrift, nowhere, bereft. The only possible response to such seeing is to lament; to turn to face our ancestors; to bury optimism as a kind of dereliction of our duty; and to learn to dance for the dead. I cannot stress starkly enough the sheer physicality of reading this book, the pain it draws forth, and not only from enduring for eight hundred pages what is unbearable to consider. There is a deeper mystery afoot and it would appear that, in the presence of words truly uttered and written, one virtually has to die to keep up one’s end of the arrangement. Most faculty, students, and administrators don’t actually think of colleges as hedge funds or hoteliers; they think, rather, that colleges charge students for teaching them. Before the coronavirus pandemic, professors would grouse that their students acted like customers who expected faculty to provide services. But it’s impossible to argue that online instruction, even when exceptionally well-executed, delivers the same quality of education as in-person teaching. I’ve been lucky: all of my students have high-speed Internet access, I have relatively small classes, and my students had a chance to get to know one another during the first six weeks of the semester. (Some of my friends who teach on different timetables met their students for the first time online.) I have done my best to compensate for what students have lost: learning by discussion, by engaging with one another and with me in ways that simply cannot be replicated online. Still, they are certainly not learning as much as they would be in person.

Most faculty, students, and administrators don’t actually think of colleges as hedge funds or hoteliers; they think, rather, that colleges charge students for teaching them. Before the coronavirus pandemic, professors would grouse that their students acted like customers who expected faculty to provide services. But it’s impossible to argue that online instruction, even when exceptionally well-executed, delivers the same quality of education as in-person teaching. I’ve been lucky: all of my students have high-speed Internet access, I have relatively small classes, and my students had a chance to get to know one another during the first six weeks of the semester. (Some of my friends who teach on different timetables met their students for the first time online.) I have done my best to compensate for what students have lost: learning by discussion, by engaging with one another and with me in ways that simply cannot be replicated online. Still, they are certainly not learning as much as they would be in person.

Some analysts are cynical about the apparent mismatch between spending and outcomes in what’s disparagingly called ‘the cancer industry’. How can cancer be the second leading cause of death globally, responsible for an estimated 9.6 million deaths in 2018, when a single institution (the US National Institutes of Health, NIH) spent US$24.4 billion on

Some analysts are cynical about the apparent mismatch between spending and outcomes in what’s disparagingly called ‘the cancer industry’. How can cancer be the second leading cause of death globally, responsible for an estimated 9.6 million deaths in 2018, when a single institution (the US National Institutes of Health, NIH) spent US$24.4 billion on  Last Thursday, Nobel-winning economist Paul Krugman issued a

Last Thursday, Nobel-winning economist Paul Krugman issued a  Artificial intelligence has made great strides of late, in areas as diverse as playing Go and recognizing pictures of dogs. We still seem to be a ways away from AI that is intelligent in the human sense, but it might not be too long before we have to start thinking seriously about the “motivations” and “purposes” of artificial agents. Stuart Russell is a longtime expert in AI, and he takes extremely seriously the worry that these motivations and purposes may be dramatically at odds with our own. In his book Human Compatible, Russell suggests that the secret is to give up on building our own goals into computers, and rather programming them to figure out our goals by actually observing how humans behave.

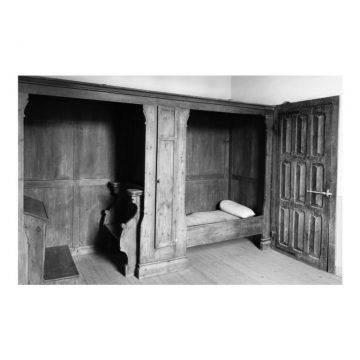

Artificial intelligence has made great strides of late, in areas as diverse as playing Go and recognizing pictures of dogs. We still seem to be a ways away from AI that is intelligent in the human sense, but it might not be too long before we have to start thinking seriously about the “motivations” and “purposes” of artificial agents. Stuart Russell is a longtime expert in AI, and he takes extremely seriously the worry that these motivations and purposes may be dramatically at odds with our own. In his book Human Compatible, Russell suggests that the secret is to give up on building our own goals into computers, and rather programming them to figure out our goals by actually observing how humans behave. The room is perhaps the fundamental element of any architecture. As a primitive hut, a simple shelter, a cave or a retreat, the room commands a unique and unrepeatable definition of a place. Making room means to clear a space for oneself: to identify a limit between inside and outside (room, from the proto-Indoeuropean root reue-“to open, space”). Like organs in a body, specific arrangements of rooms correspond to species of buildings with distinctive characteristics. Despite its concatenations, a room always preserves the possibility of autonomy, as a stand-alone entity. In the Western classical tradition—from Vitruvius to Alberti and Palladio—rooms are usually categorized according to forms accurately proportioned to their fulfilled functions.

The room is perhaps the fundamental element of any architecture. As a primitive hut, a simple shelter, a cave or a retreat, the room commands a unique and unrepeatable definition of a place. Making room means to clear a space for oneself: to identify a limit between inside and outside (room, from the proto-Indoeuropean root reue-“to open, space”). Like organs in a body, specific arrangements of rooms correspond to species of buildings with distinctive characteristics. Despite its concatenations, a room always preserves the possibility of autonomy, as a stand-alone entity. In the Western classical tradition—from Vitruvius to Alberti and Palladio—rooms are usually categorized according to forms accurately proportioned to their fulfilled functions. William Gass has written of the book’s “terminological greed,” a phrase that goes some way in preparing the reader for The Anatomy’s extraordinary surfeit. Burton the anatomist reaches us as a thoroughly modern figure, a gathering of vibrant and contradictory energies. He is a model of inconsistency, equally at home in sense and nonsense, science and superstition, asceticism and sensuality. He apologizes for the length of his digressions only to plunge into yet more. The resultant overgrowth of text is a sort of radiant miscellany; an accumulation of conjecture, proof, rumor, and heresy; endless lists of proper names, foods, herbs, symptoms, profligate et ceteras, disputations, and lengthy essays within essays. Though not itself a novel, Burton’s fabulous act of literary excess prefigures the encyclopedic postwar fictions of the twentieth century—Gravity’s Rainbow, J R, Underworld—in which poetics and technics came together to approximate the informational density of culture.

William Gass has written of the book’s “terminological greed,” a phrase that goes some way in preparing the reader for The Anatomy’s extraordinary surfeit. Burton the anatomist reaches us as a thoroughly modern figure, a gathering of vibrant and contradictory energies. He is a model of inconsistency, equally at home in sense and nonsense, science and superstition, asceticism and sensuality. He apologizes for the length of his digressions only to plunge into yet more. The resultant overgrowth of text is a sort of radiant miscellany; an accumulation of conjecture, proof, rumor, and heresy; endless lists of proper names, foods, herbs, symptoms, profligate et ceteras, disputations, and lengthy essays within essays. Though not itself a novel, Burton’s fabulous act of literary excess prefigures the encyclopedic postwar fictions of the twentieth century—Gravity’s Rainbow, J R, Underworld—in which poetics and technics came together to approximate the informational density of culture. Many countries are enduring the Hammer today: a heavy set of social distancing measures that have stopped the economy. Millions have lost their jobs, their income, their savings, their businesses, their freedom. The economic cost is brutal. Countries are desperate to know what they need to do to open up the economy again.

Many countries are enduring the Hammer today: a heavy set of social distancing measures that have stopped the economy. Millions have lost their jobs, their income, their savings, their businesses, their freedom. The economic cost is brutal. Countries are desperate to know what they need to do to open up the economy again. The Club: no literary club has ever equaled the one founded in London in 1764 by Samuel Johnson, Sir Joshua Reynolds, Edmund Burke, Oliver Goldsmith, and a handful of others, and which came to include the very brightest intellectual, artistic and political stars of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Leo Damrosch provided a close study of the Club, its members, and its doings during the first couple of decades of its long life (it still exists today), in a book I reviewed in The Hudson Review’s

The Club: no literary club has ever equaled the one founded in London in 1764 by Samuel Johnson, Sir Joshua Reynolds, Edmund Burke, Oliver Goldsmith, and a handful of others, and which came to include the very brightest intellectual, artistic and political stars of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Leo Damrosch provided a close study of the Club, its members, and its doings during the first couple of decades of its long life (it still exists today), in a book I reviewed in The Hudson Review’s  At 4:18 a.m. on February 1, 1997, a fire broke out in the Aisin Seiki company’s Factory No. 1, in Kariya, a hundred and sixty miles southwest of Tokyo. Soon, flames had engulfed the plant and incinerated the production line that made a part called a P-valve—a device used in vehicles to modulate brake pressure and prevent skidding. The valve was small and cheap—about the size of a fist, and roughly ten dollars apiece—but indispensable. The Aisin factory normally produced almost thirty-three thousand valves a day, and was, at the time, the exclusive supplier of the part for the Toyota Motor Corporation. Within hours, the magnitude of the loss was evident to Toyota. The company had adopted “just in time” (J.I.T.) production: parts, such as P-valves, were produced according to immediate needs—to precisely match the number of vehicles ready for assembly—rather than sitting around in stockpiles. But the fire had now put the whole enterprise at risk: with no inventory in the warehouse, there were only enough valves to last a single day. The production of all Toyota vehicles was about to grind to a halt. “Such is the fragility of JIT: a surprise event can paralyze entire networks and even industries,” the management scholars Toshihiro Nishiguchi and Alexandre Beaudet observed the following year, in a case study of the episode.

At 4:18 a.m. on February 1, 1997, a fire broke out in the Aisin Seiki company’s Factory No. 1, in Kariya, a hundred and sixty miles southwest of Tokyo. Soon, flames had engulfed the plant and incinerated the production line that made a part called a P-valve—a device used in vehicles to modulate brake pressure and prevent skidding. The valve was small and cheap—about the size of a fist, and roughly ten dollars apiece—but indispensable. The Aisin factory normally produced almost thirty-three thousand valves a day, and was, at the time, the exclusive supplier of the part for the Toyota Motor Corporation. Within hours, the magnitude of the loss was evident to Toyota. The company had adopted “just in time” (J.I.T.) production: parts, such as P-valves, were produced according to immediate needs—to precisely match the number of vehicles ready for assembly—rather than sitting around in stockpiles. But the fire had now put the whole enterprise at risk: with no inventory in the warehouse, there were only enough valves to last a single day. The production of all Toyota vehicles was about to grind to a halt. “Such is the fragility of JIT: a surprise event can paralyze entire networks and even industries,” the management scholars Toshihiro Nishiguchi and Alexandre Beaudet observed the following year, in a case study of the episode. Before 2015, few people would have thought of not finishing college as a public-health issue. That changed because of research done by Anne Case and Angus Deaton, economists at Princeton who are also married. For the past six years, they have been collaboratively researching an alarming long-term increase in what they call “deaths of despair” — suicides, drug overdoses, and alcoholism-related illnesses — among white non-Hispanic Americans without a bachelor’s degree in middle age.

Before 2015, few people would have thought of not finishing college as a public-health issue. That changed because of research done by Anne Case and Angus Deaton, economists at Princeton who are also married. For the past six years, they have been collaboratively researching an alarming long-term increase in what they call “deaths of despair” — suicides, drug overdoses, and alcoholism-related illnesses — among white non-Hispanic Americans without a bachelor’s degree in middle age. By the last week of January, Rob DeLeo knew it was going to get bad.

By the last week of January, Rob DeLeo knew it was going to get bad.