Zack Savitsky in Science Magazine:

Standing in a garden on the remote German island of Helgoland one day in June, two theoretical physicists quibble over who—or what—constructs reality. Carlo Rovelli, based at Aix-Marseille University, insists he is real with respect to a stone on the ground. He may cast a shadow on the stone, for instance, projecting his existence onto their relationship. Chris Fuchs of the University of Massachusetts Boston retorts that it’s preposterous to imagine the stone possessing any worldview, seeing as it is a stone. Although allied in their belief that reality is subjective rather than absolute, they both leave the impromptu debate unsatisfied, disagreeing about whether they agree.

Standing in a garden on the remote German island of Helgoland one day in June, two theoretical physicists quibble over who—or what—constructs reality. Carlo Rovelli, based at Aix-Marseille University, insists he is real with respect to a stone on the ground. He may cast a shadow on the stone, for instance, projecting his existence onto their relationship. Chris Fuchs of the University of Massachusetts Boston retorts that it’s preposterous to imagine the stone possessing any worldview, seeing as it is a stone. Although allied in their belief that reality is subjective rather than absolute, they both leave the impromptu debate unsatisfied, disagreeing about whether they agree.

Such is the state of theoretical quantum mechanics, scientists’ deepest description of the atomic world. The theory was developed 100 years ago on Helgoland, where a 23-year-old Werner Heisenberg retreated to escape a bout of hay fever—and to reimagine what an atom looks like.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Fall marks the start of Iran’s rainy season, but large parts of the country have

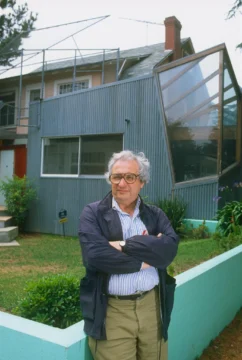

Fall marks the start of Iran’s rainy season, but large parts of the country have  Like his buildings, the legacy of Frank Gehry, who died on Dec. 5, at age 96, is exceptionally complex: radical, shifting, multifaceted and often misunderstood. It’s easy to reduce his structures to their superficialities, shapes and materials. But they’re far deeper and expansive — as has been Gehry’s impact on people, buildings, cities and the culture in general. He helped disrupt architecture and art — worlds reluctant to change. But he also changed how we see the world, shifting our perspective and our sense of what we were open to. Here are insights from some of the people he touched during his eight-decade career.

Like his buildings, the legacy of Frank Gehry, who died on Dec. 5, at age 96, is exceptionally complex: radical, shifting, multifaceted and often misunderstood. It’s easy to reduce his structures to their superficialities, shapes and materials. But they’re far deeper and expansive — as has been Gehry’s impact on people, buildings, cities and the culture in general. He helped disrupt architecture and art — worlds reluctant to change. But he also changed how we see the world, shifting our perspective and our sense of what we were open to. Here are insights from some of the people he touched during his eight-decade career. On the evening of Dec. 4, 1975, Hannah Arendt was sitting in her living room on Riverside Drive in Manhattan when she suddenly slumped over in the presence of her dinner guests. Less than two months before, she had celebrated her 69th birthday; now, she was dead from a heart attack. Arendt certainly had her share of readers and admirers, but as one of her contemporaries later put it, at the time of her death “she was scarcely considered to be a major political thinker.”

On the evening of Dec. 4, 1975, Hannah Arendt was sitting in her living room on Riverside Drive in Manhattan when she suddenly slumped over in the presence of her dinner guests. Less than two months before, she had celebrated her 69th birthday; now, she was dead from a heart attack. Arendt certainly had her share of readers and admirers, but as one of her contemporaries later put it, at the time of her death “she was scarcely considered to be a major political thinker.” M

M Complex ideas often require conditions and qualifiers to remain true. When these ideas are rounded off to something simpler (as always happens when ideas spread), the effects vary: Sometimes, a concept rounds to a simplification that still pushes beliefs toward truth.

Complex ideas often require conditions and qualifiers to remain true. When these ideas are rounded off to something simpler (as always happens when ideas spread), the effects vary: Sometimes, a concept rounds to a simplification that still pushes beliefs toward truth. Plurality voting is notorious for producing winners

Plurality voting is notorious for producing winners  M

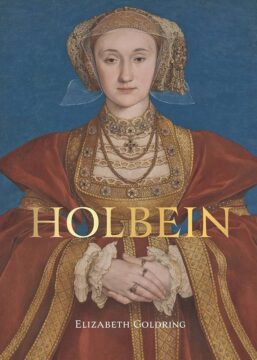

M It’s an irony to savour: the man who invented the Tudors was a German. If Henry VIII, his wives and courtiers exercise a stronger hold on the public imagination than their Plantagenet precursors or Stuart successors, it is because we can all picture them so clearly. That, in turn, is due to an extraordinary sequence of portraits and drawings produced between the late 1520s and early 1540s by Hans Holbein of Augsburg (c 1497–1543), many of which have become instantly recognisable. This familiarity, as Elizabeth Goldring notes at the outset of her superb and ground-breaking biography, means it is harder to appreciate just how novel Holbein’s portraits appeared to the first people who saw them. They marvelled, even more than we do, at Holbein’s ability to make viewers feel that they have been ‘granted access to the sitter’s inner thoughts and feelings, that Holbein has distilled the essence of the sitter’s nature and temperament in visual form’.

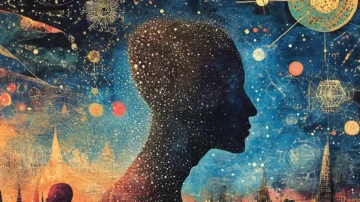

It’s an irony to savour: the man who invented the Tudors was a German. If Henry VIII, his wives and courtiers exercise a stronger hold on the public imagination than their Plantagenet precursors or Stuart successors, it is because we can all picture them so clearly. That, in turn, is due to an extraordinary sequence of portraits and drawings produced between the late 1520s and early 1540s by Hans Holbein of Augsburg (c 1497–1543), many of which have become instantly recognisable. This familiarity, as Elizabeth Goldring notes at the outset of her superb and ground-breaking biography, means it is harder to appreciate just how novel Holbein’s portraits appeared to the first people who saw them. They marvelled, even more than we do, at Holbein’s ability to make viewers feel that they have been ‘granted access to the sitter’s inner thoughts and feelings, that Holbein has distilled the essence of the sitter’s nature and temperament in visual form’. Theoretical physicist and neuroscientist Àlex Gómez-Marín argues that modern science has become trapped in a framework that mistakes matter for the whole of reality. In this wide-ranging interview, Gómez-Marín challenges the foundations of materialism, defends the scientific study of near-death experiences, and calls for a new type of science grounded in mystery and a renewed sense of the sacred. He suggests that abandoning materialism could open the door to a deeper understanding of consciousness, death, and the purpose of human existence.

Theoretical physicist and neuroscientist Àlex Gómez-Marín argues that modern science has become trapped in a framework that mistakes matter for the whole of reality. In this wide-ranging interview, Gómez-Marín challenges the foundations of materialism, defends the scientific study of near-death experiences, and calls for a new type of science grounded in mystery and a renewed sense of the sacred. He suggests that abandoning materialism could open the door to a deeper understanding of consciousness, death, and the purpose of human existence. Despite rebuttals from Pakistani authorities, social media has been exploding with

Despite rebuttals from Pakistani authorities, social media has been exploding with