Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Category: Recommended Reading

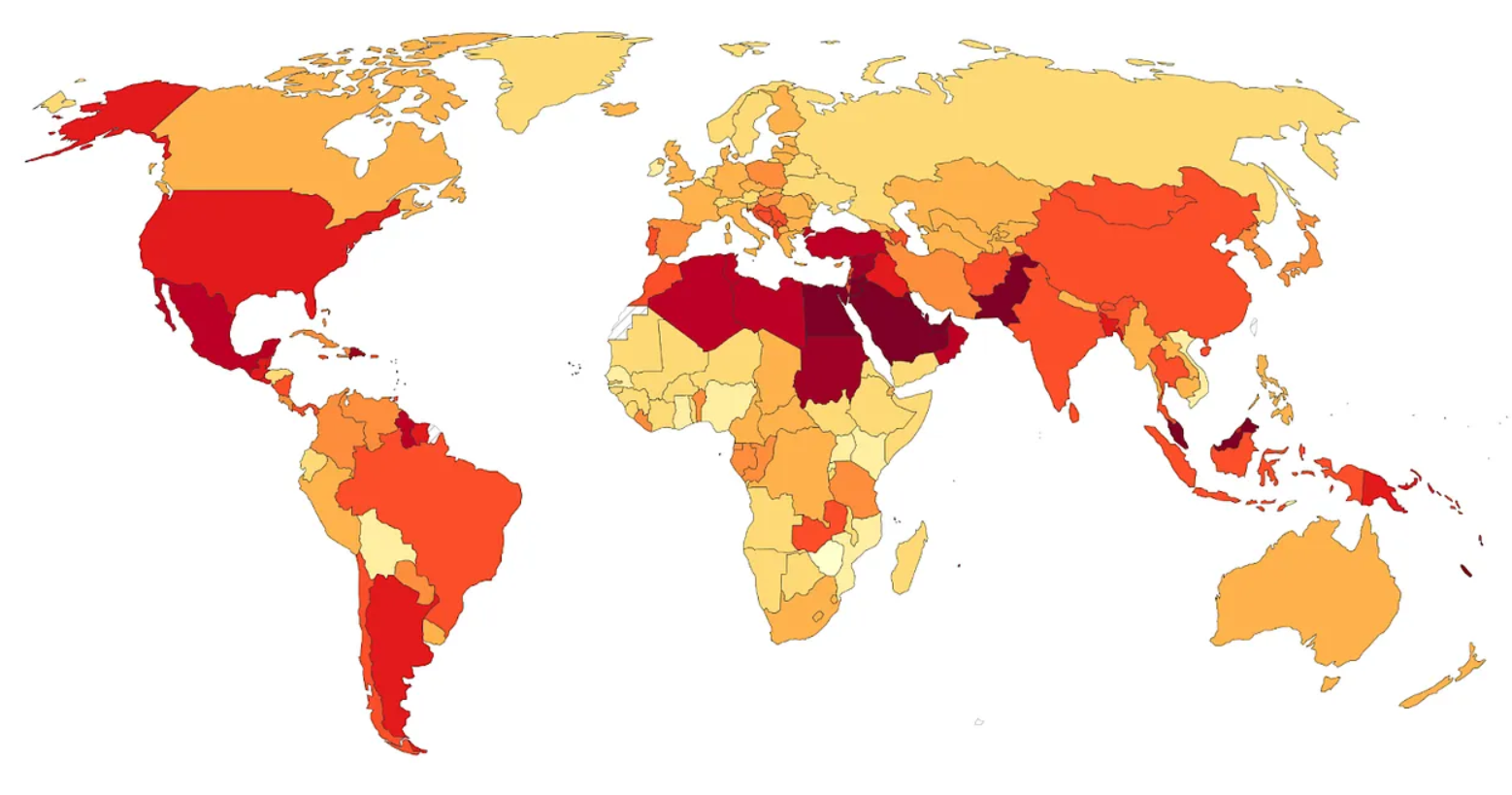

The changing (and surprising) geography of diabetes

Hannah Ritchie at By the Numbers:

Which country has the highest rates of diabetes? Many people would guess the United States. Perhaps Canada or Australia? Mexico? The United Kingdom?

Which country has the highest rates of diabetes? Many people would guess the United States. Perhaps Canada or Australia? Mexico? The United Kingdom?

According to the International Diabetes Federation, it’s Pakistan.

Take a look at the map below, which plots the prevalence of diabetes among 20 to 79-year-olds.

Now, this data is what we call “age-standardised”. The risk of diabetes, like many diseases, increases with age. So if we were to map the raw (or crude) rates of diabetes, it would strongly reflect how old populations are.

To understand changes in prevalence and risk beyond aging, we use age-standardised metrics that hold the age structure of the population constant over time and across countries. It imagines that the age distribution of every country is the same.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Jesus in the Junk Shop

Stephen Westich at The Hedgehog Review:

Investigating the crypto-religious is Elie’s venture in this book. Readers of Elie’s first two books, The Life You Save May Be Your Own and Reinventing Bach, will be familiar with his interest in complicating the boundary between secular and sacred with close readings of literary and musical works through the lens of their makers’ spiritual struggles and developments. One way he expands on these ideas in The Last Supper is by foregrounding the visual arts in his analysis. But a second, more central expansion comes from his concept of the crypto-religious. He borrows the term from the Polish poet Czesław Miłosz, who wrote to Thomas Merton that “I have always been crypto-religious and in a conflict with the political aspect of Polish Catholicism.” For Miłosz, this meant concealing his religious inclinations within his homeland’s Communist regime and alluding to early Christians hiding in Roman crypts. Elie expands the phrase to cover much more: “Crypto-religious art is work that incorporates religious words and images and motifs but expresses something other than conventional belief. It’s work that raises the question of what the person who made it believes, so that the question of what it means to believe is crucial to the work’s effect: as you see it, hear it, read it, listen to it, you wind up reflecting on your own beliefs.”

Investigating the crypto-religious is Elie’s venture in this book. Readers of Elie’s first two books, The Life You Save May Be Your Own and Reinventing Bach, will be familiar with his interest in complicating the boundary between secular and sacred with close readings of literary and musical works through the lens of their makers’ spiritual struggles and developments. One way he expands on these ideas in The Last Supper is by foregrounding the visual arts in his analysis. But a second, more central expansion comes from his concept of the crypto-religious. He borrows the term from the Polish poet Czesław Miłosz, who wrote to Thomas Merton that “I have always been crypto-religious and in a conflict with the political aspect of Polish Catholicism.” For Miłosz, this meant concealing his religious inclinations within his homeland’s Communist regime and alluding to early Christians hiding in Roman crypts. Elie expands the phrase to cover much more: “Crypto-religious art is work that incorporates religious words and images and motifs but expresses something other than conventional belief. It’s work that raises the question of what the person who made it believes, so that the question of what it means to believe is crucial to the work’s effect: as you see it, hear it, read it, listen to it, you wind up reflecting on your own beliefs.”

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

How The Fridge Destroyed One of the World’s Largest Monopolies

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

An Infinite Sadness

Rachel Gerry at the LARB:

In the genre of sanatorium literature, An Infinite Sadness stands apart. It doesn’t have much of the fellow feeling that defines Thomas Mann’s classic The Magic Mountain (1924), in which Hans Castorp, bowled over by love and intellectual companionship, struggles to leave the Berghof hospital. In Christa Wolf’s August (2012), the protagonist reflects on the affecting compassion of a fellow resident in a TB clinic, while in Ken Kesey’s One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1962), the bonds among the patients form the basis of their resistance to institutional authority. Alphonse Daudet, while seeking relief from spinal pain in a thermal spa, wrote that “the patients, in all their weirdness and diversity, draw comfort from the demonstration that their respective illnesses all have something in common.” Stories set in sanatoriums tend to show their characters slowly settling into their new homes, the world slipping away, time taking on different proportions. Separated from the imperatives of productivity, the sanatorium is an imaginative space in which the future is null and progress uncertain. As sickness becomes the rule instead of the exception, the patient begins to exist authentically, in a reality defined by a community of fellow sufferers.

In the genre of sanatorium literature, An Infinite Sadness stands apart. It doesn’t have much of the fellow feeling that defines Thomas Mann’s classic The Magic Mountain (1924), in which Hans Castorp, bowled over by love and intellectual companionship, struggles to leave the Berghof hospital. In Christa Wolf’s August (2012), the protagonist reflects on the affecting compassion of a fellow resident in a TB clinic, while in Ken Kesey’s One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1962), the bonds among the patients form the basis of their resistance to institutional authority. Alphonse Daudet, while seeking relief from spinal pain in a thermal spa, wrote that “the patients, in all their weirdness and diversity, draw comfort from the demonstration that their respective illnesses all have something in common.” Stories set in sanatoriums tend to show their characters slowly settling into their new homes, the world slipping away, time taking on different proportions. Separated from the imperatives of productivity, the sanatorium is an imaginative space in which the future is null and progress uncertain. As sickness becomes the rule instead of the exception, the patient begins to exist authentically, in a reality defined by a community of fellow sufferers.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Iranians Don’t Need to Prove Their Revolution to You

Sahar Delijani in the Los Angeles Review of Books:

I am not writing this essay as an author, nor as an activist, nor as a representative of the Iranian people. I am writing this as the daughter of former dissidents who lost the best days of their lives in the prisons of the Islamic Republic. As the daughter of a woman who was forced to give birth behind bars, interrogated while going through labor. As the niece of a man executed on a summer morning alongside thousands of others, his body swallowed by an unmarked mass grave. As the granddaughter of working-class grandparents who endured endless humiliations and hardships to raise grandchildren whose parents languished in the regime’s houses of horror.

I am not writing this essay as an author, nor as an activist, nor as a representative of the Iranian people. I am writing this as the daughter of former dissidents who lost the best days of their lives in the prisons of the Islamic Republic. As the daughter of a woman who was forced to give birth behind bars, interrogated while going through labor. As the niece of a man executed on a summer morning alongside thousands of others, his body swallowed by an unmarked mass grave. As the granddaughter of working-class grandparents who endured endless humiliations and hardships to raise grandchildren whose parents languished in the regime’s houses of horror.

I am writing this as a woman who has carried the inheritance of violence, repression and state-sponsored terror all her life, as a little girl who learned early the discipline of silence, who knew what could never be said to strangers about where her parents had been and what had been done to them.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Thursday Poem

A Violet Darkness

And all that remains for me is to follow a violet darkness

on soil where myths splinter and crack.

Yes, love was time, and it too

splintered and cracked

like the face of our country.

My share of the people

is the transit of their ghosts.

by Najwan Darwish

translated from the Arabic by Kareem James Abu-Zeid

from The Academy of American Poets

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

On Tilt: America’s new gambling epidemic

Jasper Craven in Harper’s Magazine:

Four days after online sports betting was officially launched in New York State, I got a hot tip from a football player in Pittsburgh. It was January 2022, and Ben Roethlisberger, the lumbering thirty-nine-year-old Steelers quarterback, was telling the press that his upcoming postseason bout against fellow signal-caller Patrick Mahomes and the Kansas City Chiefs wasn’t going to end well. “We probably aren’t supposed to be here,” he said. “We’re probably not a very good football team.” A few seconds later, as if his point weren’t already clear, he added, “We don’t have a chance.” I didn’t know much about sports betting, but even I could appreciate a good opportunity.

Four days after online sports betting was officially launched in New York State, I got a hot tip from a football player in Pittsburgh. It was January 2022, and Ben Roethlisberger, the lumbering thirty-nine-year-old Steelers quarterback, was telling the press that his upcoming postseason bout against fellow signal-caller Patrick Mahomes and the Kansas City Chiefs wasn’t going to end well. “We probably aren’t supposed to be here,” he said. “We’re probably not a very good football team.” A few seconds later, as if his point weren’t already clear, he added, “We don’t have a chance.” I didn’t know much about sports betting, but even I could appreciate a good opportunity.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

More than one-third of cancer cases are preventable

Flora Graham in Nature:

Nearly 40% of new cancer cases worldwide are potentially preventable, according to one of the first investigations1 of its kind, which analysed dozens of cancer types in almost 200 countries.

Nearly 40% of new cancer cases worldwide are potentially preventable, according to one of the first investigations1 of its kind, which analysed dozens of cancer types in almost 200 countries.

The study found that in 2022, roughly seven million cancer diagnoses were linked to modifiable risk factors — those that can be changed, controlled or managed to reduce the likelihood of developing the disease. Overall, tobacco smoking was the leading contributor to worldwide cancer cases, followed by infections and drinking alcohol. The findings suggest that avoiding such risk factors is “one of the most powerful ways that we can potentially reduce the future cancer burden”, says study co-author Hanna Fink, a cancer epidemiologist at the World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer in Lyon, France.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Wednesday, February 4, 2026

Michael Lentz – Basically, I Would Rather Be A Poem

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Is it Too Late to Save Hollywood?

Kyle Paoletta and A.S. Hamrah at The Nation:

Hamrah’s most recent project was Last Week in End Times Cinema, a weekly newsletter collecting together “pathetic and ridiculous” news stories about the movie business. (True to form, Hamrah blasted these digests out from his EarthLink account rather than bothering with Substack.) Those columns are now available in a separate collection as well. There are dispiriting headlines like “Winnie-the-Pooh: Blood and Honey 2 Ending Explained” and summaries of news stories about Sam Altman, the “eyebrowless CEO of OpenAI,” suggesting “AI might figure out on its own how to stop itself from ending the human race.” Read enough of these missives and it becomes obvious why studio heads were too focused on replacing actors with algorithms to properly market a film like Train Dreams, filing it away in Netflix’s library of slop after a curtailed theatrical release.

Hamrah’s most recent project was Last Week in End Times Cinema, a weekly newsletter collecting together “pathetic and ridiculous” news stories about the movie business. (True to form, Hamrah blasted these digests out from his EarthLink account rather than bothering with Substack.) Those columns are now available in a separate collection as well. There are dispiriting headlines like “Winnie-the-Pooh: Blood and Honey 2 Ending Explained” and summaries of news stories about Sam Altman, the “eyebrowless CEO of OpenAI,” suggesting “AI might figure out on its own how to stop itself from ending the human race.” Read enough of these missives and it becomes obvious why studio heads were too focused on replacing actors with algorithms to properly market a film like Train Dreams, filing it away in Netflix’s library of slop after a curtailed theatrical release.

Together, Algorithm of the Night and Last Week in End Times Cinema provide a sardonic—yet sobering—guide to the societal breakdown of 2020s America.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Moltbook: After The First Weekend

Scott Alexander at Astral Codex Ten:

What’s the difference between ‘real’ and ‘roleplaying’?

One possible answer invokes internal reality. Are the AIs conscious? Do they “really” “care” about the things they’re saying? We may never figure this out. Luckily, it has no effect on the world, so we can leave it to the philosophers1.

I find it more fruitful to think about external reality instead, especially in terms of causes and effects.

Does Moltbook have real causes?If an agent posts “I hate my life, my human is making me work on a cryptocurrency site and it’s the most annoying thing ever”, does this correspond to a true state of affairs? Is the agent really working on a cryptocurrency site? Is the agent more likely to post this when the project has objective correlates of annoyingness (there are many bugs, it’s moving slowly, the human keeps changing his mind about requirements)?

Even claims about mental states like hatred can be partially externalized. Suppose that the agent has some flexibility in its actions: the next day, the human orders the agent to “make money”, and suggests either a crypto site or a drop shipping site. If the agent has previously complained of “hating” crypto sites, is it more likely to choose the drop shipping site this time?

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Maximally Perverse Obscurantism

Paul Grimstad at The Baffler:

There is an especially gnarly chapter more than halfway through Ulysses called the “Oxen of the Sun” in which Joyce’s weirdly adversarial virtuosity takes the form of a pastiche of the evolution of English prose, which is at the same time an allegory of the nine months of fetal gestation (the chapter is set in a maternity hospital). It is mostly a slog, but it is an exhilarating slog. As you hack your way through Joyce “doing” Malory and Bunyan and Swift and Pepys and Defoe and Sterne and Goldsmith and Burke and Gibbon and Lamb and De Quincey and Carlyle and Pater, and on up to “Irish, Bowery slang and broken doggerel,” a part of your reading mind succumbs to a serenely disbelieving loop: He did this. He did this. If “Oxen” occupies a region of Ulysses where Joyce’s exquisite ear for memorably musical sentences (“Mild fire of wine kindled his veins”) takes a back seat to the leaden hum of meta-literature, that is no reason not to be awed by his chutzpah.

Michael Lentz’s Schattenfroh—rendered heroically from German into English by Max Lawton—lives mostly on the nether side of the line Joyce crossed in “Oxen.” At one thousand pages it is almost by definition a slog.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Does AI already have human-level intelligence? The evidence is clear: Yes

Eddy Keming Chen, Mikhail Belkin, Leon Bergen & David Danks in Nature:

We think the current evidence is clear. By inference to the best explanation — the same reasoning we use in attributing general intelligence to other people — we are observing AGI of a high degree. Machines such as those envisioned by Turing have arrived. Similar arguments have been made before, and have engendered controversy and push-back. Our argument benefits from substantial advances and extra time. As of early 2026, the case for AGI is considerably more clear-cut.

We think the current evidence is clear. By inference to the best explanation — the same reasoning we use in attributing general intelligence to other people — we are observing AGI of a high degree. Machines such as those envisioned by Turing have arrived. Similar arguments have been made before, and have engendered controversy and push-back. Our argument benefits from substantial advances and extra time. As of early 2026, the case for AGI is considerably more clear-cut.

We now examine ten common objections to the idea that current LLMs display general intelligence. Several of them echo objections that Turing himself considered in 1950. Each, we suggest, either conflates general intelligence with non-essential aspects of intelligence or applies standards that individual humans fail to meet.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Hairy Ball Theorem

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

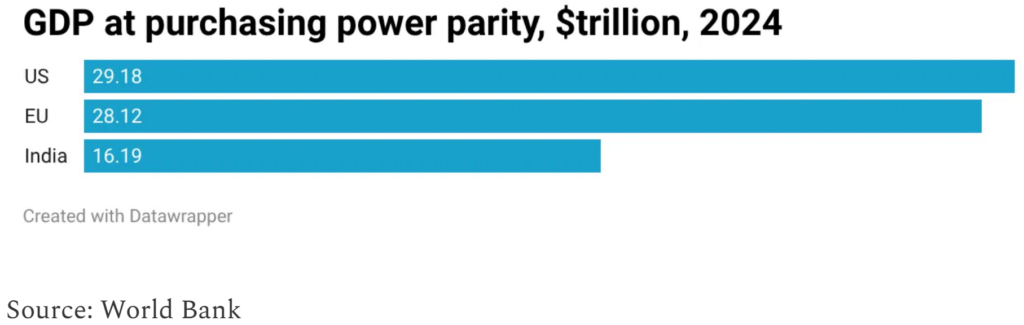

The World Files for Economic Divorce from America

Paul Krugman at his Substack:

On Monday India and the European Union concluded negotiations on a breakthrough free trade agreement. Ursula von der Leyen, the president of the European Commission — the EU’s executive branch — called it “the mother of all deals.” That description is somewhat over the top. Yet the agreement is in fact historic and important in ways that go beyond economics. For it shows that the world is becoming ever more estranged from an erratic, abusive United States. In other words, other countries are moving, step by step, toward an economic divorce from America.

Unlike Donald Trump, who thinks of international trade as a zero-sum game, the Europeans and the Indians understand that a free trade agreement between them is a very good deal for both parties. They are two very big economies. Although Trump administration officials like to sneer at European economic performance, the economy of the European Union is roughly the same size as ours.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The most important lesson from 83,000 brain scans

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Penny, a Doberman pinscher, wins the Westminster dog show

Beck and Judkis in The Washington Post:

NEW YORK — A Doberman pinscher named Penny was awarded best in show at the Westminster Kennel Club Dog Show on Tuesday night, the fifth of its breed to take the title of top dog. “You can’t attribute it to one thing, but she’s as great a Doberman as I’ve ever seen,” said her handler, Andy Linton, who previously won best in show 37 years ago and had hoped for a second victory, adding, “I had some goals, and this was one of them.”

NEW YORK — A Doberman pinscher named Penny was awarded best in show at the Westminster Kennel Club Dog Show on Tuesday night, the fifth of its breed to take the title of top dog. “You can’t attribute it to one thing, but she’s as great a Doberman as I’ve ever seen,” said her handler, Andy Linton, who previously won best in show 37 years ago and had hoped for a second victory, adding, “I had some goals, and this was one of them.”

As each of the finalists returned for judging, Madison Square Garden was lit up in purple. Shortly before she won the grand prize, Penny — or “monkey,” as her owners call her — galloped around the room, as the announcers praised her “perfect stance” and arched neck. “She’s a wonderful dog, she’s friendly,” Linton said at the news conference after Penny’s win. “Any one of you could come up here and she’d try to get you to pet her, but if you were a burglar, you wouldn’t come in our house. So, she’s got that character that a Doberman’s supposed to have.”

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Wednesday Poem

No Man is an Island

No man is an island,

Entire of itself,

Every man is a piece of the continent,

A part of the main.

If a clod be washed away by the sea,

Europe is the less.

As well as if a promontory were.

As well as if a manor of thy friend’s

Or of thine own were:

Any man’s death diminishes me,

Because I am involved in mankind,

And therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls;

It tolls for thee.

by John Donne

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Tuesday, February 3, 2026

Review of “The Bed Trick” by Izabella Scott – a bizarre story of sexual duplicity

Olivia Laing in The Guardian:

In September 2015, Gayle Newland stood trial accused of sex by deception. It was alleged that she created an online identity as a man and used this character, Kye Fortune, to lure another woman into a sexual relationship, which was consummated repeatedly with the assistance of a blindfold and a prosthetic penis. The woman believed she was having sex with Kye until one day her ring caught on his hat and she felt long hair. Tearing off her blindfold, she realised her male lover was actually her female friend. As these lurid, almost fairytale details seeped out, the case went viral. “Sex attacker who posed as man found guilty” was one of the milder headlines.

In September 2015, Gayle Newland stood trial accused of sex by deception. It was alleged that she created an online identity as a man and used this character, Kye Fortune, to lure another woman into a sexual relationship, which was consummated repeatedly with the assistance of a blindfold and a prosthetic penis. The woman believed she was having sex with Kye until one day her ring caught on his hat and she felt long hair. Tearing off her blindfold, she realised her male lover was actually her female friend. As these lurid, almost fairytale details seeped out, the case went viral. “Sex attacker who posed as man found guilty” was one of the milder headlines.

The trial caught Izabella Scott’s attention because it was a real-life example of a plot device she recognised from literature. The bed trick can be found in folk stories and operas, in Chaucer and Shakespeare. Often told for comic effect, it concerns sex by trickery and deception, under cover of darkness. “The plot suggests,” Scott writes, “that, in bed, anyone might be mistaken for anyone else.”

It dropped out of literary fashion with the invention of artificial light, but here it was again, unfolding in a 21st-century court of law.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.