Andrea Lius in The Scientist:

Adult ants that have been infected with deadly pathogens often leave the colony to die so as not to infect others. But, “like infected cells in tissue, [young ants] are largely immobile and lack this option,” said Sylvia Cremer, a researcher at the Institute of Science and Technology Austria (ISTA) who studies how social insects such as ants fight diseases collectively as superorganisms, in a statement. Cremer’s team previously found that invasive garden ant pupae that have been infected with a deadly fungal pathogen produced chemicals that induced worker ants to unpack their cocoons and kill them, preventing the disease from spreading to the rest of the colony.1 However, the researchers did not know if the chemicals were simply a result of the fungal infection or if the sick pupae specifically released them to call for their own demise.

Adult ants that have been infected with deadly pathogens often leave the colony to die so as not to infect others. But, “like infected cells in tissue, [young ants] are largely immobile and lack this option,” said Sylvia Cremer, a researcher at the Institute of Science and Technology Austria (ISTA) who studies how social insects such as ants fight diseases collectively as superorganisms, in a statement. Cremer’s team previously found that invasive garden ant pupae that have been infected with a deadly fungal pathogen produced chemicals that induced worker ants to unpack their cocoons and kill them, preventing the disease from spreading to the rest of the colony.1 However, the researchers did not know if the chemicals were simply a result of the fungal infection or if the sick pupae specifically released them to call for their own demise.

In a new study, Cremer and her colleagues discovered that the infected pupae only released chemicals when there were workers nearby, suggesting that the sick young ants put these events in motion.2 The researchers’ findings, published in Nature Communications, are the first evidence of altruistic disease signaling in a social insects and share similarities with how sick and dying cells send a “find me and eat me” signal to the immune system.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

She certainly doesn’t want to be idolised as a saint – that rarely ends well, and besides, she holds grudges. She even chafes against her mantle as feminist icon, “expected to do the Right Thing for women in all circumstances, with many different Right Things projected on to me from readers and viewers”, as she writes in Book of Lives.

She certainly doesn’t want to be idolised as a saint – that rarely ends well, and besides, she holds grudges. She even chafes against her mantle as feminist icon, “expected to do the Right Thing for women in all circumstances, with many different Right Things projected on to me from readers and viewers”, as she writes in Book of Lives.

As Michael Billington put it in a

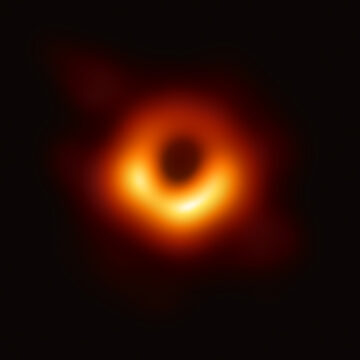

As Michael Billington put it in a  What came first, the chicken or the egg? Perhaps a silly conundrum already solved by Darwinian biology. But nature has supplied us with a real version of this puzzle: black holes. Within these cosmic objects, the extreme warping of spacetime brings past and future together, making it hard to tell what came first. Black holes also blur the distinction between matter and energy, fusing them into a single entity. In this sense, they also warp our everyday intuitions about space, time and causality, making them both chicken and egg at once.

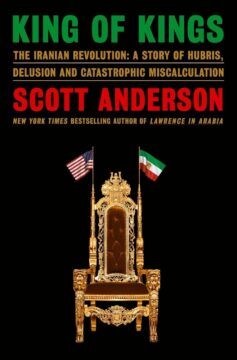

What came first, the chicken or the egg? Perhaps a silly conundrum already solved by Darwinian biology. But nature has supplied us with a real version of this puzzle: black holes. Within these cosmic objects, the extreme warping of spacetime brings past and future together, making it hard to tell what came first. Black holes also blur the distinction between matter and energy, fusing them into a single entity. In this sense, they also warp our everyday intuitions about space, time and causality, making them both chicken and egg at once. Scott Anderson begins his latest book, King of Kings: The Iranian Revolution; A Story of Hubris, Delusion and Catastrophic Miscalculation (2025), with the story of an infamous 1971 party in a desert. The king of Anderson’s title, Iran’s shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, was ostensibly marking 2,500 years of the Persian empire in Persepolis, once the capital under Cyrus the Great, who founded the Achaemenid Empire around 550 BCE. At a time of political stress, the shah was making a bid to link the Pahlavi dynasty, and himself in particular, to Cyrus, as the basis of an unquestionable legitimacy—“his rule and his achievements forming a continuum with those of the ancient immortals,” in Anderson’s words.

Scott Anderson begins his latest book, King of Kings: The Iranian Revolution; A Story of Hubris, Delusion and Catastrophic Miscalculation (2025), with the story of an infamous 1971 party in a desert. The king of Anderson’s title, Iran’s shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, was ostensibly marking 2,500 years of the Persian empire in Persepolis, once the capital under Cyrus the Great, who founded the Achaemenid Empire around 550 BCE. At a time of political stress, the shah was making a bid to link the Pahlavi dynasty, and himself in particular, to Cyrus, as the basis of an unquestionable legitimacy—“his rule and his achievements forming a continuum with those of the ancient immortals,” in Anderson’s words. The curiosity that drove the Irish novelist Maggie O’Farrell to write her bestselling 2020 novel Hamnet sprang from the scarcity of documentation about the book’s title character, Hamnet Shakespeare. Born in 1585 to William and Anne Shakespeare, the twin brother to a girl named Judith, Hamnet died of unknown causes in 1596, the only one of the Shakespeares’ three children not to reach adulthood. But for the records of his christening and his burial in the Stratford-upon-Avon parish registers, Hamnet’s 11 years on earth remain a tantalizing blank, one of those countless human existences that are legible to us now only in the form of a bookended pair of dates.

The curiosity that drove the Irish novelist Maggie O’Farrell to write her bestselling 2020 novel Hamnet sprang from the scarcity of documentation about the book’s title character, Hamnet Shakespeare. Born in 1585 to William and Anne Shakespeare, the twin brother to a girl named Judith, Hamnet died of unknown causes in 1596, the only one of the Shakespeares’ three children not to reach adulthood. But for the records of his christening and his burial in the Stratford-upon-Avon parish registers, Hamnet’s 11 years on earth remain a tantalizing blank, one of those countless human existences that are legible to us now only in the form of a bookended pair of dates. Earl Gray was astonished by what he found when he cut into the laboratory rats. Some had testicles that were malformed, filled with fluid, missing or in the wrong place. Others had shriveled tubes blocking the flow of sperm, while still more were missing glands that help produce semen. For months, Gray and his team had been feeding rats corn oil laced with phthalates, a class of chemical widely used to make plastics soft and pliable. Working for the Environmental Protection Agency in the early 1980s, Gray was evaluating how toxic substances damage the reproductive system and tested dibutyl phthalate after reading some early papers suggesting it posed a risk to human health.

Earl Gray was astonished by what he found when he cut into the laboratory rats. Some had testicles that were malformed, filled with fluid, missing or in the wrong place. Others had shriveled tubes blocking the flow of sperm, while still more were missing glands that help produce semen. For months, Gray and his team had been feeding rats corn oil laced with phthalates, a class of chemical widely used to make plastics soft and pliable. Working for the Environmental Protection Agency in the early 1980s, Gray was evaluating how toxic substances damage the reproductive system and tested dibutyl phthalate after reading some early papers suggesting it posed a risk to human health. The Polish poet Czesław Miłosz (1911–2004) had a complicated Second World War. He was in Warsaw when the Germans invaded, fleeing then to Ukraine. But then, discovering that his wife had been unable to escape Poland, he tried to return to her by way of Romania, then Ukraine again—the Germans were coming from one direction, the Russians from another—then Lithuania. By the summer of 1940, he was back in Warsaw. There, he participated in various underground activities, including the sheltering and transportation of Jews. In 1944, he was captured and briefly held in an internment camp. As the Red Army moved closer to Warsaw and the Nazis burned the city in anticipatory vengeance, Miłosz and his wife, with little more than the clothes on their backs, made their way to a village near Kraków, finding a brief respite from history, though not from poverty.

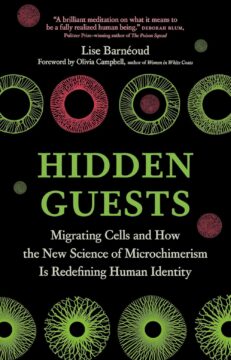

The Polish poet Czesław Miłosz (1911–2004) had a complicated Second World War. He was in Warsaw when the Germans invaded, fleeing then to Ukraine. But then, discovering that his wife had been unable to escape Poland, he tried to return to her by way of Romania, then Ukraine again—the Germans were coming from one direction, the Russians from another—then Lithuania. By the summer of 1940, he was back in Warsaw. There, he participated in various underground activities, including the sheltering and transportation of Jews. In 1944, he was captured and briefly held in an internment camp. As the Red Army moved closer to Warsaw and the Nazis burned the city in anticipatory vengeance, Miłosz and his wife, with little more than the clothes on their backs, made their way to a village near Kraków, finding a brief respite from history, though not from poverty. A biological phenomenon, microchimerism refers to the presence of a small number of cells from one individual within another genetically distinct individual. It most commonly occurs during pregnancy when fetal cells escape into the mother’s bloodstream or maternal cells sneak into the placenta, eventually becoming part of the embryo or fetus. Likewise, twins may exchange cells before birth, too.

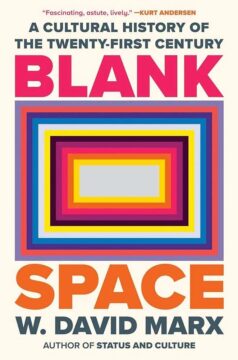

A biological phenomenon, microchimerism refers to the presence of a small number of cells from one individual within another genetically distinct individual. It most commonly occurs during pregnancy when fetal cells escape into the mother’s bloodstream or maternal cells sneak into the placenta, eventually becoming part of the embryo or fetus. Likewise, twins may exchange cells before birth, too. Marx, in my opinion, is a woefully underrated thinker on culture. His first book,

Marx, in my opinion, is a woefully underrated thinker on culture. His first book,  W

W From restoring movement and speech in people with paralysis to fighting depression,

From restoring movement and speech in people with paralysis to fighting depression,

Several years ago, I stopped going to therapy. I no longer trusted myself to tell the story of my life in a way that felt forward-moving. I harbored a suspicion that the therapist held some knowledge of me that she would one day reveal — like whether I should switch careers or move — but she never did.

Several years ago, I stopped going to therapy. I no longer trusted myself to tell the story of my life in a way that felt forward-moving. I harbored a suspicion that the therapist held some knowledge of me that she would one day reveal — like whether I should switch careers or move — but she never did.