Rachel Fieldhouse & Mohana Basu in Nature:

For Susan Sawyer, a physician-researcher specializing in adolescent health at the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute in Melbourne, Australia, the start of the social-media ban this week meant entering the next phase of her research. Over the past two months, Sawyer and her colleagues interviewed 177 teenagers aged 13–16 about their social-media use, screen time and mental health before the ban came into effect. She and her colleagues plan to survey the teenagers again in six months, to see whether the ban has affected their use of the platforms or their mental health. The researchers will also survey the participants’ parents about problematic Internet and social-media use by their children.

For Susan Sawyer, a physician-researcher specializing in adolescent health at the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute in Melbourne, Australia, the start of the social-media ban this week meant entering the next phase of her research. Over the past two months, Sawyer and her colleagues interviewed 177 teenagers aged 13–16 about their social-media use, screen time and mental health before the ban came into effect. She and her colleagues plan to survey the teenagers again in six months, to see whether the ban has affected their use of the platforms or their mental health. The researchers will also survey the participants’ parents about problematic Internet and social-media use by their children.

Another research collaboration between the Kids Research Institute Australia, the University of Western Australia and Edith Cowan University, all in Perth, will examine whether the ban is presenting new parenting challenges and what family conflicts have arisen as a result.

Amanda Third, a researcher at Western Sydney University in Australia who studies how children use technology, says the ban is an opportunity to collect data about the effect of policies that restrict young people’s access to the Internet and social media.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

I first encountered Zheng Xiaoqiong’s writing in

I first encountered Zheng Xiaoqiong’s writing in  We tend to think of religion as an age-old feature of human existence. So it can be startling to learn that the very concept dates to the early modern era. Yes, you find gods, temples, sacrifices and rituals in the ancient Mediterranean, classical China, pre-Columbian Mesoamerica. What you don’t find is a term that quite maps onto ‘religion’.

We tend to think of religion as an age-old feature of human existence. So it can be startling to learn that the very concept dates to the early modern era. Yes, you find gods, temples, sacrifices and rituals in the ancient Mediterranean, classical China, pre-Columbian Mesoamerica. What you don’t find is a term that quite maps onto ‘religion’. Peck focuses on what Orwell got brilliantly right – about fascism, communism, imperialism, nationalism, the abuses of new technology and the lies people tell themselves without necessarily realising. But even when Orwell was proved wrong, which was often, he was wrong in a sincere and interesting way. To quote his disclaimer in Homage to Catalonia, ‘I warn everyone against my bias, and I warn everyone against my mistakes. Still, I have done my best to be honest.’

Peck focuses on what Orwell got brilliantly right – about fascism, communism, imperialism, nationalism, the abuses of new technology and the lies people tell themselves without necessarily realising. But even when Orwell was proved wrong, which was often, he was wrong in a sincere and interesting way. To quote his disclaimer in Homage to Catalonia, ‘I warn everyone against my bias, and I warn everyone against my mistakes. Still, I have done my best to be honest.’ After the long, torturous summers that bake northern India in 40-degree Celsius (104 degree Fahrenheit) heat, winter should be welcomed as a reprieve. Instead, it is our season of sadness. The annual pollution emergency faced by hundreds of millions of Indians is upon us — three months of physical and emotional suffocation. I live in Delhi, one of the

After the long, torturous summers that bake northern India in 40-degree Celsius (104 degree Fahrenheit) heat, winter should be welcomed as a reprieve. Instead, it is our season of sadness. The annual pollution emergency faced by hundreds of millions of Indians is upon us — three months of physical and emotional suffocation. I live in Delhi, one of the

I chose the green door ninety-three days ago. At the time, it seemed obviously correct. Not even a close call. The red door offered two billion dollars immediately—a sum so large it would solve every material problem I’d ever face, fund any project I could imagine, and still leave enough to give away amounts that would meaningfully change thousands of lives. But two billion is a number. It has a fixed relationship to the economy, to the things money can buy, to the world. The green door offered one dollar that doubles every day. I remember standing there, doing the mental math. Day 30: about a billion dollars. Day 40: over a trillion. Day 50: a quadrillion. The red door would be surpassed before the first month ended, and after that, the gap would grow incomprehensibly fast. Choosing the red door would be like choosing a ham sandwich over a genie’s lamp because you were hungry right now. So I walked through the green door. The first few weeks were unremarkable.

I chose the green door ninety-three days ago. At the time, it seemed obviously correct. Not even a close call. The red door offered two billion dollars immediately—a sum so large it would solve every material problem I’d ever face, fund any project I could imagine, and still leave enough to give away amounts that would meaningfully change thousands of lives. But two billion is a number. It has a fixed relationship to the economy, to the things money can buy, to the world. The green door offered one dollar that doubles every day. I remember standing there, doing the mental math. Day 30: about a billion dollars. Day 40: over a trillion. Day 50: a quadrillion. The red door would be surpassed before the first month ended, and after that, the gap would grow incomprehensibly fast. Choosing the red door would be like choosing a ham sandwich over a genie’s lamp because you were hungry right now. So I walked through the green door. The first few weeks were unremarkable. On today’s show, Wesley reveals his favorite film performances of the year — but his list is not an ordinary best-of list. He zeroes in on the specific details that make a performance great. Like, who did the best acting in a helmet this year? Who were the most convincing on-screen best friends? And who refused to play it safe? Find out in our first annual Cannonball Great Performers special.

On today’s show, Wesley reveals his favorite film performances of the year — but his list is not an ordinary best-of list. He zeroes in on the specific details that make a performance great. Like, who did the best acting in a helmet this year? Who were the most convincing on-screen best friends? And who refused to play it safe? Find out in our first annual Cannonball Great Performers special. “Let Paul Robeson singing Water Boy and Rudolph Fisher writing about the streets of Harlem … cause the smug Negro middle class to turn from their white, respectable, ordinary books and papers to catch a glimmer of their own beauty.” So wrote Langston Hughes in his landmark 1926 essay “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain.” Today, Paul Robeson—singer, actor, athlete, lawyer, antiracism icon—needs no introduction. But who was Rudolph Fisher?

“Let Paul Robeson singing Water Boy and Rudolph Fisher writing about the streets of Harlem … cause the smug Negro middle class to turn from their white, respectable, ordinary books and papers to catch a glimmer of their own beauty.” So wrote Langston Hughes in his landmark 1926 essay “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain.” Today, Paul Robeson—singer, actor, athlete, lawyer, antiracism icon—needs no introduction. But who was Rudolph Fisher? Forrest Gander is on good terms with the mineral world, and he’s made a habit in his poetry of displaying a deep familiarity with the layers of sediment below our feet. His expertise—Gander is a geologist by training—has allowed him to convert technical terms (such as rift zone, ilmenite, and olivine) into lyrical tools that capture rarefied emotional states and complex systems of relation. So it’s natural that his latest collection, Mojave Ghost, opens with an act of geophagy. “The first dirt I tasted was a fistful of siltstone dust outside the house where I was born in the Mojave Desert,” Gander writes in a brief preface. The dirt, the rocks, the minerals that make up the earth around him are an index of intimacy, of a time and place that shaped his fluid sensibility. Melding the human and nonhuman realms becomes an act of self-recognition for Gander, granting a deeper understanding of himself and the setting of his birth.

Forrest Gander is on good terms with the mineral world, and he’s made a habit in his poetry of displaying a deep familiarity with the layers of sediment below our feet. His expertise—Gander is a geologist by training—has allowed him to convert technical terms (such as rift zone, ilmenite, and olivine) into lyrical tools that capture rarefied emotional states and complex systems of relation. So it’s natural that his latest collection, Mojave Ghost, opens with an act of geophagy. “The first dirt I tasted was a fistful of siltstone dust outside the house where I was born in the Mojave Desert,” Gander writes in a brief preface. The dirt, the rocks, the minerals that make up the earth around him are an index of intimacy, of a time and place that shaped his fluid sensibility. Melding the human and nonhuman realms becomes an act of self-recognition for Gander, granting a deeper understanding of himself and the setting of his birth. Thomas Manning arrived in Lhasa in 1811, having walked for months across the Himalayas from Calcutta, disguised as a Buddhist pilgrim and accompanied only by a single Chinese servant, with whom he spoke in Latin. He was the first Englishman to enter the city, the only one to do so in the entire nineteenth century, and the first European to meet the Dalai Lama, then still a child.

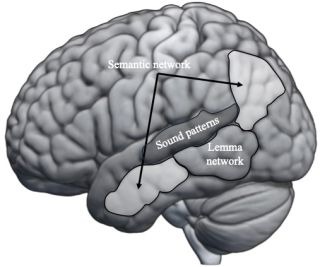

Thomas Manning arrived in Lhasa in 1811, having walked for months across the Himalayas from Calcutta, disguised as a Buddhist pilgrim and accompanied only by a single Chinese servant, with whom he spoke in Latin. He was the first Englishman to enter the city, the only one to do so in the entire nineteenth century, and the first European to meet the Dalai Lama, then still a child. How is it that words can be so common, so fundamental, yet so elusive? A key discovery is that words are not just a sound pattern (cat, gato, neko) and a meaning (furry-domesticated-meows), but also contain something in between, a kind of “middle word,” which psycholinguists refer to as a lemma. The name comes from mathematics, where it refers to an intermediate step in a theorem. You can think of word lemmas as the hidden network that computes the translation between word sound and word meaning. How do we know lemmas exist? There are several bits of evidence, including computational arguments,

How is it that words can be so common, so fundamental, yet so elusive? A key discovery is that words are not just a sound pattern (cat, gato, neko) and a meaning (furry-domesticated-meows), but also contain something in between, a kind of “middle word,” which psycholinguists refer to as a lemma. The name comes from mathematics, where it refers to an intermediate step in a theorem. You can think of word lemmas as the hidden network that computes the translation between word sound and word meaning. How do we know lemmas exist? There are several bits of evidence, including computational arguments,