Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Category: Recommended Reading

On Fascist Passions in Mussolini’s Italy

Tia Glista at LitHub:

A squad of amateur fascists feast around a table at a busy restaurant, their eyes flicking from their meal toward a crowd across the room, and then to their de facto leader, a balding 35-year-old newspaper man. They practically hover above their chairs, panting, licking their lips, gripping their glasses of wine instead of drinking from them: they are poised for something else, and so they check in again with their boss, whose curt nod gives them assent to take action. They leap up, bludgeon the other men with batons and kick them repeatedly; a few days later, they perform a similar attack on the headquarters of the socialist newspaper L’Avanti, smashing their equipment, stabbing their workers, lighting people and things on fire. The year is 1919 and the man who leads the squadrismo is Benito Mussolini.

A squad of amateur fascists feast around a table at a busy restaurant, their eyes flicking from their meal toward a crowd across the room, and then to their de facto leader, a balding 35-year-old newspaper man. They practically hover above their chairs, panting, licking their lips, gripping their glasses of wine instead of drinking from them: they are poised for something else, and so they check in again with their boss, whose curt nod gives them assent to take action. They leap up, bludgeon the other men with batons and kick them repeatedly; a few days later, they perform a similar attack on the headquarters of the socialist newspaper L’Avanti, smashing their equipment, stabbing their workers, lighting people and things on fire. The year is 1919 and the man who leads the squadrismo is Benito Mussolini.

When watching Mussolini: Son of the Century, the new mini-series directed by Joe Wright and based on the 2018 novel by Antonio Scurati, it was not the fact of the violence that surprised me so much as the extent of its heedlessness—the open, unreserved character of the cruelty inflicted on others in public without remorse.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Wednesday Poem

A Ghazal of Mangoes

up a part of herself if she chooses to go where a man goes.

……

The Complete Notebooks By Albert Camus

Joanna Kavenna at Literary Review:

There’s a surreal television interview with Camus at the Parc des Princes stadium in Paris, during a football match between Racing Club de Paris and AS Monaco. It’s 1957 and Camus has recently won the Nobel Prize. The interviewer asks for a few thoughts from Camus on why he won. ‘Well, I don’t know,’ says Camus. ‘I’m not privy to the secrets of the Swedish Academy. But there are two or three writers who deserved the prize before me.’ He’s also invited to criticise the Racing Club goalkeeper. A former goalkeeper himself (for the Racing Universitaire d’Alger), Camus says, ‘Don’t blame him. If you were out there in the middle you’d realise how difficult it is.’ Notable aspects of this interview are: Camus’s diffident charm, how he never stops watching the game, how he seems more interested in football than in speaking of the Nobel. The same wry, self-deprecating tone courses through his notebooks, the same natural gift for aphorisms. The notebooks were published in French between 1962 and 1989; previous English translations have appeared, including by Philip Thody. Now, they have been published for the first time in a single volume, beautifully translated by the author and scholar Ryan Bloom.

There’s a surreal television interview with Camus at the Parc des Princes stadium in Paris, during a football match between Racing Club de Paris and AS Monaco. It’s 1957 and Camus has recently won the Nobel Prize. The interviewer asks for a few thoughts from Camus on why he won. ‘Well, I don’t know,’ says Camus. ‘I’m not privy to the secrets of the Swedish Academy. But there are two or three writers who deserved the prize before me.’ He’s also invited to criticise the Racing Club goalkeeper. A former goalkeeper himself (for the Racing Universitaire d’Alger), Camus says, ‘Don’t blame him. If you were out there in the middle you’d realise how difficult it is.’ Notable aspects of this interview are: Camus’s diffident charm, how he never stops watching the game, how he seems more interested in football than in speaking of the Nobel. The same wry, self-deprecating tone courses through his notebooks, the same natural gift for aphorisms. The notebooks were published in French between 1962 and 1989; previous English translations have appeared, including by Philip Thody. Now, they have been published for the first time in a single volume, beautifully translated by the author and scholar Ryan Bloom.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Tuesday, January 6, 2026

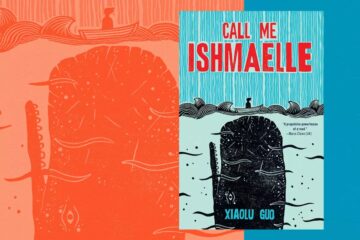

The literary remix trend comes for Moby-Dick — and it’s a triumph

Leanne Ogasawara at the Los Angeles Times:

“Call me Ishmael.”

“Call me Ishmael.”

Considered one of the greatest opening lines in all of literary history, it must have been almost irresistible for the acclaimed novelist Xiaolu Guo to resist using it for the title of her 2025 retelling of the world’s most famous whale tale, “Moby-Dick”. But Guo makes a major change; for in her story, the young and sometimes gloomy male protagonist has been transformed into an adventurous young woman.

This has been such a great few years for retellings of the classics — from Barbara Kingsolver’s updated David Copperfield to Salman Rushdie’s zany Don Quixote. And Percival Everett’s novel “James,” a retelling of Huckleberry Finn, took the lion’s share of the literary prizes in 2024, including the Pulitzer. There is so much pleasure to be had in rereading old favorites — and part of the joy is meeting beloved characters, who have been updated or somehow arrive in a new form to resist old tropes and types.

Guo’s recasting of Ishmaelle is no exception.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

It is our moral duty to strike back at the Universe

Drew M Dalton in Aeon:

Reality, as we now understand, does not tend towards existential flourishing and eternal becoming. Instead, systems collapse, things break down, and time tends irreversibly towards disorder and eventual annihilation. Rather than something to align with, the Universe appears to be fundamentally hostile to our wellbeing.

Reality, as we now understand, does not tend towards existential flourishing and eternal becoming. Instead, systems collapse, things break down, and time tends irreversibly towards disorder and eventual annihilation. Rather than something to align with, the Universe appears to be fundamentally hostile to our wellbeing.

According to the laws of thermodynamics, all that exists does so solely to consume, destroy and extinguish, and in this way to accelerate the slide toward cosmic obliteration. For these reasons, the thermodynamic revolution in our understanding of the order and operation of reality is more than a scientific development. It is also more than a simple revision of our understanding of the flow of heat, and it does more than help us design more efficient engines. It ruptures our commonly held beliefs concerning the nature and value of existence, and it demands a new metaphysics, bold new ethical principles and alternative aesthetic models.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Progress made on AI-powered humanoid robots

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Where does a liberal go from here?

Noah Smith at Noahpinion:

Imagine, then, standing in 1815, a quarter century after the Revolution, looking back at what it had all become. That first bright rush of freedom had given way, first to the murderous insanity of the Terror and the Committee for Public Safety, then to the thuggish new imperialism and endless bloody wars of Napoleon, and finally to the fall of all Europe to conservative reaction under the Congress of Vienna. Imagine looking back on the arc of your beliefs, your movement, and your life, now as an old man, with no prospects for another, better Revolution ahead of you.

Imagine, then, standing in 1815, a quarter century after the Revolution, looking back at what it had all become. That first bright rush of freedom had given way, first to the murderous insanity of the Terror and the Committee for Public Safety, then to the thuggish new imperialism and endless bloody wars of Napoleon, and finally to the fall of all Europe to conservative reaction under the Congress of Vienna. Imagine looking back on the arc of your beliefs, your movement, and your life, now as an old man, with no prospects for another, better Revolution ahead of you.

Would you think your dreams had failed? Would you decide that everything you had believed had been an illusion, and that freedom, democracy, and the Rights of Man were false idols that led only to chaos and bloodshed?

If so, you would be utterly wrong. The two centuries after 1815 would see the ideals of the early French Revolutionaries continue to advance across the world — unevenly, in fits and starts, and with many reversals, yet almost always leaving society better off than before.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

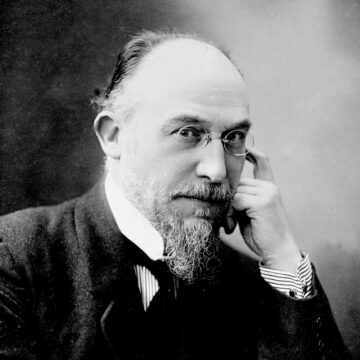

Satie’s Spell

Jeremy Denk at the NYRB:

What is the point? is of course one of the main points of Satie. You don’t get the same sensation, for instance, listening to The Rite of Spring, Salome, Wozzeck, or Pierrot lunaire. As shocking or boundary-testing as those modernist masterpieces may be, they all have a point, and they work. They offer dramatic shapes, vectors, formal conceits; they expose sharp contrasts or conflicts. Mostly, Satie’s pieces don’t work in those ways, and they leave the question of a point open at best.

What is the point? is of course one of the main points of Satie. You don’t get the same sensation, for instance, listening to The Rite of Spring, Salome, Wozzeck, or Pierrot lunaire. As shocking or boundary-testing as those modernist masterpieces may be, they all have a point, and they work. They offer dramatic shapes, vectors, formal conceits; they expose sharp contrasts or conflicts. Mostly, Satie’s pieces don’t work in those ways, and they leave the question of a point open at best.

So how exactly does Satie take down the arrogance of late Romantic classical music? Consider the Sarabandes, Satie’s first suite of dances, from September of 1887. They begin with three lubricious seventh chords. The last, a chord that “should” lead forward, sits and lingers in the air. We hear five more chords, full of branching possibilities—but end up in the same place. This feels a bit neutralizing, if not yet frustrating. The third phrase travels more purposefully, and we soon arrive at an A major chord—a normal triad. But it’s notated on the page as arcane B-double-flat major, making it hard to read and even more irritating to write about. (A trivial distinction that also screws with your head is a perennial Satie combination.) This is the first of many arrivals sprinkled about the score, an abundance of goals that paradoxically don’t produce a sense of direction.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Erik Satie: Gymnopédies & Gnossiennes

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

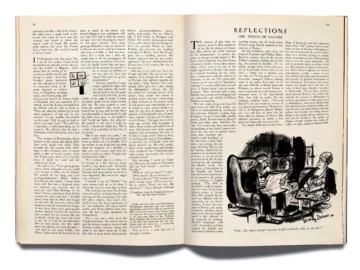

An Essay On An Essay By Mary McCarthy

Katy Waldman at The New Yorker:

Like novelistic interludes concerning pine forests, McCarthy’s breed of criticism feels endangered. The breezy authority, the absurd plenitude: these qualities suggest a more hospitable era for the printed word, even if you prefer today’s careful efficiency. That McCarthy rarely bothers to explain her voluminous references evokes a time when the writer’s job was less to make thinking easy than to make it rewarding. “One Touch of Nature” supplies the loveliness it praises, pausing to describe “the still, ribbony roads leading nowhere” in paintings by the Dutch artist Jacob van Ruisdael (whereas the essay itself is a snarl of colored lines on an M.T.A. map, leading everywhere at once) and “the snow in ‘The Dead’ falling softly over Ireland, a universal blanket or shroud.” As McCarthy surveys her subject, she conjures a living artistic ecosystem that is constantly evolving, including in its relationship to the natural world. The subtext is that this system, like the carbon-based one, is beautiful and worth attending to; McCarthy, novelist that she is, encrypts her themes on the way to elucidating them.

Like novelistic interludes concerning pine forests, McCarthy’s breed of criticism feels endangered. The breezy authority, the absurd plenitude: these qualities suggest a more hospitable era for the printed word, even if you prefer today’s careful efficiency. That McCarthy rarely bothers to explain her voluminous references evokes a time when the writer’s job was less to make thinking easy than to make it rewarding. “One Touch of Nature” supplies the loveliness it praises, pausing to describe “the still, ribbony roads leading nowhere” in paintings by the Dutch artist Jacob van Ruisdael (whereas the essay itself is a snarl of colored lines on an M.T.A. map, leading everywhere at once) and “the snow in ‘The Dead’ falling softly over Ireland, a universal blanket or shroud.” As McCarthy surveys her subject, she conjures a living artistic ecosystem that is constantly evolving, including in its relationship to the natural world. The subtext is that this system, like the carbon-based one, is beautiful and worth attending to; McCarthy, novelist that she is, encrypts her themes on the way to elucidating them.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Why Peter Scholze is once in a Generation Mathematician

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

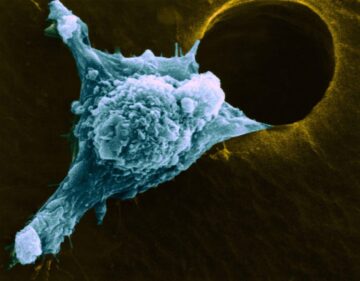

Why cancer can come back years later — and how to stop it

Amanda Heidt in Nature:

When Lisa Dutton was declared free of breast cancer in 2017, she took a moment to celebrate with family and friends, even though she knew her cancer journey might not be over. As many as one-third of people whose breast tumours are cleared see the disease come back, sometimes decades later. Many other cancers are known to recur in the years following an initial treatment, some at much higher rates.

When Lisa Dutton was declared free of breast cancer in 2017, she took a moment to celebrate with family and friends, even though she knew her cancer journey might not be over. As many as one-third of people whose breast tumours are cleared see the disease come back, sometimes decades later. Many other cancers are known to recur in the years following an initial treatment, some at much higher rates.

“It’s always in the back of your mind, and that can be stressful,” says Dutton, a retired health-care management consultant living in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. As part of her treatment, Dutton had enrolled in a clinical trial called SURMOUNT. This would monitor her for sleeping cancer cells, which many researchers now think might explain at least some cancer recurrence1. These dormant tumour cells evade initial treatment and move to other parts of the body. Instead of multiplying to form tumours right away — as is typical for metastatic cancer, in which cells spread from the main tumour — the dormant cells remain asleep. They are hidden from the immune system and not actively dividing. But later, they can reawaken and give rise to tumours.

Even though Dutton understood that her treatment might not have removed all signs of cancer, she says she was floored in 2020 when dormant cells were found in her bone marrow for the first time.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Tuesday Poem

The Horizon of Being

As far as my love of the clarity and transparency

of Galileo’s writing allows me to decipher the

deliberate obscurity of Heidegger’s language that

“time temporalizes itself only

to the extent that it is human,”

for him also, time is the time of

mankind. the time for doing, for that

with which mankind is engaged

even if, afterward, since he is

interested in what being is for man,

“the entity that poses the problem of existence”,

Heidegger ends up by identifying the internal

consciousness of time as the horizon of being itself.

by Carlo Rovelli

from The Order of Time

Riverhead Books, 2018

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Monday, January 5, 2026

Decoding the Pyramid Statues of King Menkaure

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Review of “This Is Where the Serpent Lives” by Daniyal Mueenuddin

Patrick Gale in The Guardian:

Imagine a shattering portrayal of Pakistani life through a chain of interlocking novellas, and you’ll be somewhere close to understanding the breadth and impact of Daniyal Mueenuddin’s first novel. Reminiscent of Neel Mukherjee’s dazzling circular depiction of Indian inequalities, A State of Freedom, it’s a keenly anticipated follow-up to the acclaimed short-story collection with which he made his debut in 2009, In Other Rooms, Other Wonders – also portraying overlapping worlds of Pakistani class and culture.

We begin in the squalor and bustle of a Rawalpindi bazaar in the 1950s, where the heartbreaking figure of a small child, abandoned to his fate and clutching a pair of plastic shoes, is scooped under the protection of a tea stall owner. He proceeds to raise the boy as his own son, having only daughters, but Yazid is also adopted by the stall’s garrulous regulars, who teach him both to read and to pay keen attention to the currents of class, wealth and power which flow past him every day.

Loved, popular, clever, Yazid grows into a bull of a teenager with keen entrepreneurial instincts; he soon makes the tea stall, and his shack behind it, the cool place for a gang of privileged schoolboys to hang out, smoke and play games.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Tree Killers

Rosa Lyster at Harper’s Magazine:

It is not clear how Carruthers and Graham imagined the public would respond. The tree was a beloved landmark, its silhouette an instantly recognizable symbol of England’s North East. As virtually every news report would go on to stress, it had also been featured in the 1991 movie Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves. The two men must have anticipated that people in the area would be upset. It seems implausible, though, that they had in mind what actually ended up happening, which is that the felling of the Sycamore Gap tree made international news straightaway. It became one of the biggest stories in England, prompting a prolonged nationwide spasm of outrage and what sometimes looked like genuine grief.

It is not clear how Carruthers and Graham imagined the public would respond. The tree was a beloved landmark, its silhouette an instantly recognizable symbol of England’s North East. As virtually every news report would go on to stress, it had also been featured in the 1991 movie Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves. The two men must have anticipated that people in the area would be upset. It seems implausible, though, that they had in mind what actually ended up happening, which is that the felling of the Sycamore Gap tree made international news straightaway. It became one of the biggest stories in England, prompting a prolonged nationwide spasm of outrage and what sometimes looked like genuine grief.

It was as if there had been a cosmic violation. The lamentation went far beyond those with a personal link to the tree—everyone who had hiked there, or gotten engaged there, or scattered ashes there, or even seen it from their car as they drove by. People across the country spoke of slaughter, and compared its loss to that of a close family member, or to the death of Princess Diana.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

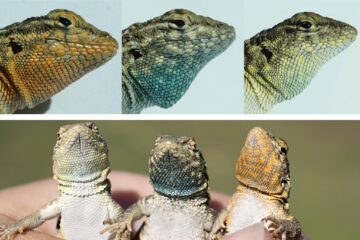

This Lizard Plays Rock-Paper-Scissors

Carl Zimmer in the New York Times:

If you live in the United States, chances are you’re familiar with the game rock-paper-scissors. You put out your hand in one of three gestures: clenching it in a fist (rock), holding it out flat (paper) or holding up two fingers in a “V” (scissors). Rock beats scissors, scissors beat paper and paper beats rock.

If you live in the United States, chances are you’re familiar with the game rock-paper-scissors. You put out your hand in one of three gestures: clenching it in a fist (rock), holding it out flat (paper) or holding up two fingers in a “V” (scissors). Rock beats scissors, scissors beat paper and paper beats rock.

Americans by no means have a monopoly on the game. People play it around the world in many variations, and under many names. In Japan, where the game has existed for thousands of years, it’s known as janken. In Indonesia, it’s known as earwig-man-elephant: The elephant kills the man, the man kills the earwig and the earwig crawls up through the elephant’s trunk and eats its brain.

The game is so common that it exists beyond our own species. Over millions of years, animals have evolved their own version of rock-paper-scissors. For them, winning the game means passing down their genes to future generations. A study published on Thursday in the journal Science reveals the hidden biology that makes the game possible — and shows how it may be an important source of nature’s diversity.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

New York City Mayor Zohran Mamdani’s full speech after taking oath of office

And read “The Moral Imagination of Mamdani” by Corey Robin here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

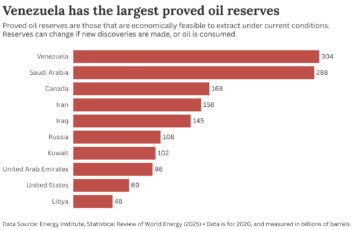

Giving some context to Venezuelan oil

Hannah Ritchie at By the Numbers:

Over the weekend, the United States bombed Venezuela, and captured its president Nicolás Maduro. There has been a lot of speculation about the legality, true motive and implications going forward.

Over the weekend, the United States bombed Venezuela, and captured its president Nicolás Maduro. There has been a lot of speculation about the legality, true motive and implications going forward.

Oil has been a central part of the discussion. I wanted to get a quick overview of what the global picture looks like. So here are five(ish) simple charts that give some context on the history of oil in Venezuela, and why the United States — which is, by far, the world’s largest producer itself — would care so much.

While we often think about the Middle East when it comes to large oil stocks, it’s Venezuela that has the largest proved reserves in the world.

The chart below shows the ten countries with the largest proved oil reserves. These are deposits that are deemed economically feasible to extract under current market conditions. This number can change as new reserves are found, or become economic.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.