Oliver Traldi at The Point:

The emotional experience of direct and renewed acquaintance with the realities of selective pressure, such as the sudden introduction of sexual jealousy into a seemingly safe relationship, has had for me an almost mystical character, as though what’s reawakened is the prehistory of my whole species, which unwinds from its reptilian recesses, ornamented with the bizarre, gemlike contingencies of thousands of howling animal triumphs and the wailing ghosts of unmutated failures, splitting my consciousness as though from underneath, a whole ocean bursting forth from the sudden shift of tectonic plates; but this alarming thing that emerges, this dark uncoiling dragon capable of incomprehensible violence, seems also dimly recognizable as simply, in some sense, my own self.

The emotional experience of direct and renewed acquaintance with the realities of selective pressure, such as the sudden introduction of sexual jealousy into a seemingly safe relationship, has had for me an almost mystical character, as though what’s reawakened is the prehistory of my whole species, which unwinds from its reptilian recesses, ornamented with the bizarre, gemlike contingencies of thousands of howling animal triumphs and the wailing ghosts of unmutated failures, splitting my consciousness as though from underneath, a whole ocean bursting forth from the sudden shift of tectonic plates; but this alarming thing that emerges, this dark uncoiling dragon capable of incomprehensible violence, seems also dimly recognizable as simply, in some sense, my own self.

It does not strike me as a coincidence that it is quite often the wild and dominating natural action of just these tidal forces which women seem to desire as consumers of the theater that is sometimes called kink. This provokes a feeling of being perceived, qua man, as though across a vast and ugly distance: radically unfamiliar and, as a happy result, perhaps competent in the contemporary eroticism exemplified by “romantasy”—romance books in which female leads liaise with creatures like giants, minotaurs, vampires and werewolves.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Let’s talk about a very 21st century scene. There’s an incident somewhere in the United States. The incident slots itself in neatly along the lines of preexisting ideological divisions. As the incident is unfolding, witnesses pull out their cell phone cameras to record it and those images are soon plastered across the web. Everybody sees essentially the same scene and everybody draws drastically different conclusions, depending on what their prior political convictions happen to be. And the result is a society split almost perfectly in two—disagreeing not only about underlying principles but even about which camera angles of an event, and which speed of playback, and which audio track, it prefers to focus on.

Let’s talk about a very 21st century scene. There’s an incident somewhere in the United States. The incident slots itself in neatly along the lines of preexisting ideological divisions. As the incident is unfolding, witnesses pull out their cell phone cameras to record it and those images are soon plastered across the web. Everybody sees essentially the same scene and everybody draws drastically different conclusions, depending on what their prior political convictions happen to be. And the result is a society split almost perfectly in two—disagreeing not only about underlying principles but even about which camera angles of an event, and which speed of playback, and which audio track, it prefers to focus on. When my daughter

When my daughter  D

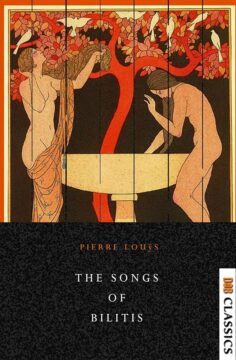

D In 1894, a German archaeologist named Herr G Heim made a groundbreaking discovery. On the island of Cyprus, he excavated a tomb that belonged to a hitherto unknown ancient female poet by the name of Bilitis. Carved on the walls surrounding her sarcophagus were more than 150 ancient Greek poems in which Bilitis recounted her life, from her childhood in Pamphylia in present-day Turkey to her adventures on the islands of Lesbos and Cyprus, where she would eventually come to rest. Heim diligently copied down this treasure trove of poems, which had not seen the light of day for more than two millennia. They would have remained little known – accessible only to a small, scholarly audience who could decipher ancient Greek – had a Frenchman named Pierre Louÿs not taken it upon himself to hunt down Heim’s Greek edition, hot off the press, and translated Bilitis’s poetry into French for a broader reading public that same year (published as Les Chansons de Bilitis or The Songs of Bilitis). Bilitis might have been an obscure historical figure – no other ancient author mentions encountering her or her poetry – but the cultural and literary significance of Heim’s discovery was not lost on Louÿs. For, in several of her poems, Bilitis revealed that she crossed paths with classical antiquity’s most renowned and controversial female poet: Sappho.

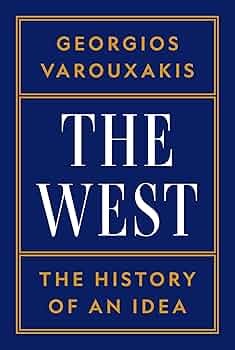

In 1894, a German archaeologist named Herr G Heim made a groundbreaking discovery. On the island of Cyprus, he excavated a tomb that belonged to a hitherto unknown ancient female poet by the name of Bilitis. Carved on the walls surrounding her sarcophagus were more than 150 ancient Greek poems in which Bilitis recounted her life, from her childhood in Pamphylia in present-day Turkey to her adventures on the islands of Lesbos and Cyprus, where she would eventually come to rest. Heim diligently copied down this treasure trove of poems, which had not seen the light of day for more than two millennia. They would have remained little known – accessible only to a small, scholarly audience who could decipher ancient Greek – had a Frenchman named Pierre Louÿs not taken it upon himself to hunt down Heim’s Greek edition, hot off the press, and translated Bilitis’s poetry into French for a broader reading public that same year (published as Les Chansons de Bilitis or The Songs of Bilitis). Bilitis might have been an obscure historical figure – no other ancient author mentions encountering her or her poetry – but the cultural and literary significance of Heim’s discovery was not lost on Louÿs. For, in several of her poems, Bilitis revealed that she crossed paths with classical antiquity’s most renowned and controversial female poet: Sappho. Varouxakis’s book is primarily about Westerners’ own conception of the West — an approach that allows him to prove that even within the so-called West, the notion was not a coherent container. It is as much a history of terms and discourses as it is about ideas, and it starts the historical clock on those terms pointedly late. Most historians trace the concept of the West back to Herodotus in the fifth century BC, when the “western” Greeks fought the “eastern” Persians. In fact, Varouxakis writes, “‘The West’ as a potential political entity based on civilisational commonality is a modern idea that arose in the first half of the nineteenth century.”

Varouxakis’s book is primarily about Westerners’ own conception of the West — an approach that allows him to prove that even within the so-called West, the notion was not a coherent container. It is as much a history of terms and discourses as it is about ideas, and it starts the historical clock on those terms pointedly late. Most historians trace the concept of the West back to Herodotus in the fifth century BC, when the “western” Greeks fought the “eastern” Persians. In fact, Varouxakis writes, “‘The West’ as a potential political entity based on civilisational commonality is a modern idea that arose in the first half of the nineteenth century.” Many of us experience a

Many of us experience a

My husband and I, newlyweds of just one year, live an ordinary life. We drag each other to Costco on Saturdays, jointly complain about how much we hate a specific restaurant on the Delmar Loop, and endlessly debate the China and America relationship. Yes, he walks through the world with the undeniable privileges of a White American man. And yes, his “expert” insights into China often leave me caught between a laugh and a heavy sigh.

My husband and I, newlyweds of just one year, live an ordinary life. We drag each other to Costco on Saturdays, jointly complain about how much we hate a specific restaurant on the Delmar Loop, and endlessly debate the China and America relationship. Yes, he walks through the world with the undeniable privileges of a White American man. And yes, his “expert” insights into China often leave me caught between a laugh and a heavy sigh.

L

L F

F “The relation between the chauffeur and the chauffeured can be curiously intense,” Iris Murdoch wrote in “The Sea, the Sea.” This was true in David Szalay’s Booker Prize-winning novel “Flesh” (2025) and it is also true in Daniyal Mueenuddin’s sensitive and powerful first novel, “This Is Where the Serpent Lives,” set largely in rural Pakistan.

“The relation between the chauffeur and the chauffeured can be curiously intense,” Iris Murdoch wrote in “The Sea, the Sea.” This was true in David Szalay’s Booker Prize-winning novel “Flesh” (2025) and it is also true in Daniyal Mueenuddin’s sensitive and powerful first novel, “This Is Where the Serpent Lives,” set largely in rural Pakistan. In recent years, scientists have begun to use magic effects to investigate the blind spots in our attention and perception [G. Kuhn, Experiencing the Impossible: The Science of Magic (2019); S. Macknik, S. Martinez-Conde, S. Blakeslee, Sleights of Mind: What the Neuroscience of Magic Reveals about Our Everyday Deceptions (2010)]. Recently, we suggested that similar techniques could be transferred to nonhuman animal observers and that such an endeavor would provide insight into the inherent commonalities and discrepancies in attention and perception in human and nonhuman animals [E. Garcia-Pelegrin, A. K. Schnell, C. Wilkins, N. S. Clayton, Science 369, 1424–1426 (2020)]. Here, we performed three different magic effects (palming, French drop, and fast pass) to a sample of six Eurasian jays (Garrulus glandarius). These magic effects were specifically chosen as they utilize different cues and expectations that mislead the spectator into thinking one object has or has not been transferred from one hand to the other.

In recent years, scientists have begun to use magic effects to investigate the blind spots in our attention and perception [G. Kuhn, Experiencing the Impossible: The Science of Magic (2019); S. Macknik, S. Martinez-Conde, S. Blakeslee, Sleights of Mind: What the Neuroscience of Magic Reveals about Our Everyday Deceptions (2010)]. Recently, we suggested that similar techniques could be transferred to nonhuman animal observers and that such an endeavor would provide insight into the inherent commonalities and discrepancies in attention and perception in human and nonhuman animals [E. Garcia-Pelegrin, A. K. Schnell, C. Wilkins, N. S. Clayton, Science 369, 1424–1426 (2020)]. Here, we performed three different magic effects (palming, French drop, and fast pass) to a sample of six Eurasian jays (Garrulus glandarius). These magic effects were specifically chosen as they utilize different cues and expectations that mislead the spectator into thinking one object has or has not been transferred from one hand to the other.