Steve Ayan in Scientific American:

In 1909 five men converged on Clark University in Massachusetts to conquer the New World with an idea. At the head of this little troupe was psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud. Ten years earlier Freud had introduced a new treatment for what was called “hysteria” in his book The Interpretation of Dreams. This work also introduced a scandalous view of the human psyche: underneath the surface of consciousness roils a largely inaccessible cauldron of deeply rooted drives, especially of sexual energy (the libido). These drives, held in check by socially inculcated morality, vent themselves in slips of the tongue, dreams and neuroses. The slips in turn provide evidence of the unconscious mind. At the invitation of psychologist G. Stanley Hall, Freud delivered five lectures at Clark. In the audience was philosopher William James, who had traveled from Harvard University to meet Freud. It is said that, as James departed, he told Freud, “The future of psychology belongs to your work.” And he was right.

In 1909 five men converged on Clark University in Massachusetts to conquer the New World with an idea. At the head of this little troupe was psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud. Ten years earlier Freud had introduced a new treatment for what was called “hysteria” in his book The Interpretation of Dreams. This work also introduced a scandalous view of the human psyche: underneath the surface of consciousness roils a largely inaccessible cauldron of deeply rooted drives, especially of sexual energy (the libido). These drives, held in check by socially inculcated morality, vent themselves in slips of the tongue, dreams and neuroses. The slips in turn provide evidence of the unconscious mind. At the invitation of psychologist G. Stanley Hall, Freud delivered five lectures at Clark. In the audience was philosopher William James, who had traveled from Harvard University to meet Freud. It is said that, as James departed, he told Freud, “The future of psychology belongs to your work.” And he was right.

The view that human beings are driven by dark emotional forces over which they have little or no control remains widespread. In this conception, the urgings of the conscious mind constantly battle the secret desires of the unconscious. Just how rooted the idea of a dark unconscious has become in popular culture can be seen in the 2015 Pixar film Inside Out. Here the unconscious mind of a girl named Riley is filled with troublemakers and fears and housed in a closed space. People like to think of the unconscious as a place where we can shove uncomfortable thoughts and impulses because we want to believe that conscious thought directs our actions; if it did not, we would seemingly have no control over our lives.

This image could hardly be less accurate, however. Recent research indicates that conscious and the unconscious processes do not usually operate in opposition. They are not competitors wrestling for hegemony over our psyche. They are not even separate spheres, as Freud’s later classification into the ego, id and superego would suggest. Rather there is only one mind in which conscious and unconscious strands are interwoven. In fact, even our most reasonable thoughts and actions mainly result from automatic, unconscious processes.

More here.

Whether you are an optimist or a pessimist is not just a question of personal temperament. It is also, increasingly, a question of politics. The divide between the optimists and the pessimists is as acute as any in contemporary politics and like many others—the generational divide between old and young, the educational divide between people who did and didn’t go to college—it cuts across left and right. There are left pessimists and right pessimists; left optimists and right optimists. What there isn’t is much common ground between them. Competing views about whether the world is getting better or worse has become another dialogue of the deaf.

Whether you are an optimist or a pessimist is not just a question of personal temperament. It is also, increasingly, a question of politics. The divide between the optimists and the pessimists is as acute as any in contemporary politics and like many others—the generational divide between old and young, the educational divide between people who did and didn’t go to college—it cuts across left and right. There are left pessimists and right pessimists; left optimists and right optimists. What there isn’t is much common ground between them. Competing views about whether the world is getting better or worse has become another dialogue of the deaf.

Nowhere else in the world did the year 1984 fulfill its apocalyptic portents as it did in India. Separatist violence in the Punjab, the military attack on the great Sikh temple of Amritsar; the assassination of the Prime Minister, Mrs Indira Gandhi; riots in several cities; the gas disaster in Bhopal – the events followed relentlessly on each other. There were days in 1984 when it took courage to open the New Delhi papers in the morning.

Nowhere else in the world did the year 1984 fulfill its apocalyptic portents as it did in India. Separatist violence in the Punjab, the military attack on the great Sikh temple of Amritsar; the assassination of the Prime Minister, Mrs Indira Gandhi; riots in several cities; the gas disaster in Bhopal – the events followed relentlessly on each other. There were days in 1984 when it took courage to open the New Delhi papers in the morning. Dana, you’re absolutely right to wonder what happened to The Tale; it’s exactly the kind of movie I have in mind, underseen despite tackling one of the most urgent subjects of our moment. I may have seen better movies overall this year, but I don’t think any of them had a conceit that shook me as deeply as this one. It all comes down to a simple, harrowing thing that Jennifer Fox does to depict how the heroine of the film, also named Jennifer Fox (and played by Laura Dern), remembers a sexual relationship she had with her tennis coach as a teenager. She initially remembers herself as confident and sexually self-possessed; she remembers herself, in other words, as a young woman somewhat in control of what happened to her, and, as the movie reveals, this has led her to remember what happened as a more consensual affair, rather than as abuse.

Dana, you’re absolutely right to wonder what happened to The Tale; it’s exactly the kind of movie I have in mind, underseen despite tackling one of the most urgent subjects of our moment. I may have seen better movies overall this year, but I don’t think any of them had a conceit that shook me as deeply as this one. It all comes down to a simple, harrowing thing that Jennifer Fox does to depict how the heroine of the film, also named Jennifer Fox (and played by Laura Dern), remembers a sexual relationship she had with her tennis coach as a teenager. She initially remembers herself as confident and sexually self-possessed; she remembers herself, in other words, as a young woman somewhat in control of what happened to her, and, as the movie reveals, this has led her to remember what happened as a more consensual affair, rather than as abuse. Peter Carruthers, Distinguished University Professor of Philosophy at the University of Maryland, College Park, is an expert on the philosophy of mind who draws heavily on empirical psychology and cognitive neuroscience. He outlined many of his ideas on conscious thinking in his 2015 book The Centered Mind: What the Science of Working Memory Shows Us about the Nature of Human Thought. More recently, in 2017, he published a paper with the astonishing title of “The Illusion of Conscious Thought.” In the following excerpted conversation, Carruthers explains to editor Steve Ayan the reasons for his provocative proposal.

Peter Carruthers, Distinguished University Professor of Philosophy at the University of Maryland, College Park, is an expert on the philosophy of mind who draws heavily on empirical psychology and cognitive neuroscience. He outlined many of his ideas on conscious thinking in his 2015 book The Centered Mind: What the Science of Working Memory Shows Us about the Nature of Human Thought. More recently, in 2017, he published a paper with the astonishing title of “The Illusion of Conscious Thought.” In the following excerpted conversation, Carruthers explains to editor Steve Ayan the reasons for his provocative proposal. “Are we all Joyceans here, then?” the young professor asked, poking his head into the classroom doorway.

“Are we all Joyceans here, then?” the young professor asked, poking his head into the classroom doorway. Media coverage of uncontacted tribes often delights in painting indigenous groups as people out of time, hunter-gatherers in the age of Seamless. In November, an American missionary was killed trying to reach North Sentinel Island in the Bay of Bengal, home to a remote tribe thought to number about 100 people. Grainy images shot from a helicopter in 2004 of naked islanders brandishing spears flooded the internet. But when they first appear in Piripkura, Pakyî and Tamandua offer a different kind of spectacle. What is striking about them is not their timelessness, but rather their very modern resolve to persist against the odds, to be free from the outside world.

Media coverage of uncontacted tribes often delights in painting indigenous groups as people out of time, hunter-gatherers in the age of Seamless. In November, an American missionary was killed trying to reach North Sentinel Island in the Bay of Bengal, home to a remote tribe thought to number about 100 people. Grainy images shot from a helicopter in 2004 of naked islanders brandishing spears flooded the internet. But when they first appear in Piripkura, Pakyî and Tamandua offer a different kind of spectacle. What is striking about them is not their timelessness, but rather their very modern resolve to persist against the odds, to be free from the outside world. Nearly two decades ago, photo historian Douglas Nickel observed that traditional art history had not yet developed the tools for handling non-art photographs.

Nearly two decades ago, photo historian Douglas Nickel observed that traditional art history had not yet developed the tools for handling non-art photographs. Rooney’s second novel, “

Rooney’s second novel, “ Hundreds of doctors packed an auditorium at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center on Oct. 1, deeply angered by revelations that the hospital’s top medical officer and other leaders had cultivated lucrative relationships with for-profit companies. One by one, they stood up to challenge the stewardship of their beloved institution, often to emotional applause. Some speakers accused their leaders of letting the quest to make more money undermine the hospital’s mission. Others bemoaned a rigid, hierarchical management that had left them feeling they had no real voice in the hospital’s direction. “Slowly, I’ve seen more and more of the higher-up meetings happening with people who are dressed up in suits as opposed to white coats,” said Dr. Viviane Tabar,

Hundreds of doctors packed an auditorium at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center on Oct. 1, deeply angered by revelations that the hospital’s top medical officer and other leaders had cultivated lucrative relationships with for-profit companies. One by one, they stood up to challenge the stewardship of their beloved institution, often to emotional applause. Some speakers accused their leaders of letting the quest to make more money undermine the hospital’s mission. Others bemoaned a rigid, hierarchical management that had left them feeling they had no real voice in the hospital’s direction. “Slowly, I’ve seen more and more of the higher-up meetings happening with people who are dressed up in suits as opposed to white coats,” said Dr. Viviane Tabar,

“I’m on a roadside perch,” writes Ghalib in a letter, “lounging on a takht, enjoying the sunshine, writing this letter. The weather is cold…,” he continues, as he does in most letters, with a ticklish observation or a humble admission ending on a philosophical note, a comment tinged with great sadness or a remark of wild irreverence fastened to a mystic moment. These are fragments recognized in Urdu as literary gems because they were penned by a genius, but to those of us hungry for the short-lived world that shaped classical Urdu, those distanced from that world in time and place, Ghalib’s letters chronicle what is arguably the height of Urdu’s efflorescence as well as its most critical transitions as an elite culture that found itself wedged between empires (the Mughal and the British), and eventually, many decades after Ghalib’s death, between two countries (Pakistan and India).

“I’m on a roadside perch,” writes Ghalib in a letter, “lounging on a takht, enjoying the sunshine, writing this letter. The weather is cold…,” he continues, as he does in most letters, with a ticklish observation or a humble admission ending on a philosophical note, a comment tinged with great sadness or a remark of wild irreverence fastened to a mystic moment. These are fragments recognized in Urdu as literary gems because they were penned by a genius, but to those of us hungry for the short-lived world that shaped classical Urdu, those distanced from that world in time and place, Ghalib’s letters chronicle what is arguably the height of Urdu’s efflorescence as well as its most critical transitions as an elite culture that found itself wedged between empires (the Mughal and the British), and eventually, many decades after Ghalib’s death, between two countries (Pakistan and India).

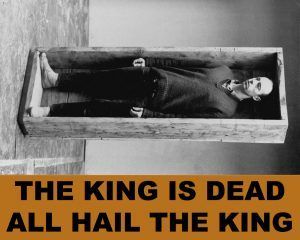

Robert Morris died last month on November 28th at the ripe old age of 87. Very ripe indeed. If he was a fig he’d have been all jammy inside, dribbling the honeyed sugars of maturation. But he’s dead, and I’m glad he’s dead. Let me step back before explaining why – this isn’t an exposition, this is an obituary; I’m grieving; this is diffused ramblings at a podium. I went to Hunter College for undergraduate philosophy and flirted with the art department quite a bit. Morris’ legacy loomed large and hard over the department as he had both attended grad school and taught there. Any course in the art department was bound to encounter his work or his writings. I must have been assigned “Notes on Sculpture” a dozen times. Morris was, and still is, a great artist. His was a scholarly brand of art; neither annoying like Joseph Kosuth, nor dehydrated like Hans Haacke. No, Morris was a genuine student of art and thought. He studied its history, wrote about it emphatically, and contributed to its heritage. It is not difficult to view him as one of the several pillars that contemporary art stands upon today, and feel indebted to his legacy. One of his first well regarded artworks was Box for Standing, which was a handmade wooden box roughly the size of a coffin that fit Morris neatly. How fitting then, that his exit from this life should perhaps be in a box bespoke for his corpse, roughly the same size as his original Box? His expiration has a funny effect on that work, Box for Standing, where his actual death gives the work one last veneer of meaning to stack upon all the other layers. One might have seen similarity between the Box for Standing and funerary vessels before Morris died, but afterward it would be reckless not to see it. The work goes from being a sparse theatrical gesture contained in minimal sculpture, to something like a pragmatic Quaker coffin, verging on bleak humor.

Robert Morris died last month on November 28th at the ripe old age of 87. Very ripe indeed. If he was a fig he’d have been all jammy inside, dribbling the honeyed sugars of maturation. But he’s dead, and I’m glad he’s dead. Let me step back before explaining why – this isn’t an exposition, this is an obituary; I’m grieving; this is diffused ramblings at a podium. I went to Hunter College for undergraduate philosophy and flirted with the art department quite a bit. Morris’ legacy loomed large and hard over the department as he had both attended grad school and taught there. Any course in the art department was bound to encounter his work or his writings. I must have been assigned “Notes on Sculpture” a dozen times. Morris was, and still is, a great artist. His was a scholarly brand of art; neither annoying like Joseph Kosuth, nor dehydrated like Hans Haacke. No, Morris was a genuine student of art and thought. He studied its history, wrote about it emphatically, and contributed to its heritage. It is not difficult to view him as one of the several pillars that contemporary art stands upon today, and feel indebted to his legacy. One of his first well regarded artworks was Box for Standing, which was a handmade wooden box roughly the size of a coffin that fit Morris neatly. How fitting then, that his exit from this life should perhaps be in a box bespoke for his corpse, roughly the same size as his original Box? His expiration has a funny effect on that work, Box for Standing, where his actual death gives the work one last veneer of meaning to stack upon all the other layers. One might have seen similarity between the Box for Standing and funerary vessels before Morris died, but afterward it would be reckless not to see it. The work goes from being a sparse theatrical gesture contained in minimal sculpture, to something like a pragmatic Quaker coffin, verging on bleak humor.  JOHN MCDONNELL IS CAGEY

JOHN MCDONNELL IS CAGEY  Bellini was probably even younger than Mantegna when he first saw his new relative’s Presentation of Christ in the Temple – art historians will never stop worrying about his exact birthdate. (He may have been Jacopo Bellini’s illegitimate son. Records are scarce. Mantegna was the child of a carpenter, from a very ordinary village. His birthdate is also unknown.) When Bellini turned back to The Presentation of Christ in the Temple twenty years later he was the master of a new style, and dialogue with Mantegna had established itself as an aspect of that mastery – his great Agony in the Garden, done in response to a panel by his brother-in-law, lay behind him. It is hard, therefore, not to see the redoing of The Presentation of Christ in the Temple as some kind of contest as well as homage. But I found myself as I looked convinced that for Bellini what counted most was the opportunity, within the confines of someone else’s invention, to reflect on – to discover – what his own art most deeply consisted of. Oil paint versus tempera made many things clear. And, further, coming to terms with the true nature of one’s art – one’s necessary medium – meant coming closer to the mysteries enounced in Luke’s text.

Bellini was probably even younger than Mantegna when he first saw his new relative’s Presentation of Christ in the Temple – art historians will never stop worrying about his exact birthdate. (He may have been Jacopo Bellini’s illegitimate son. Records are scarce. Mantegna was the child of a carpenter, from a very ordinary village. His birthdate is also unknown.) When Bellini turned back to The Presentation of Christ in the Temple twenty years later he was the master of a new style, and dialogue with Mantegna had established itself as an aspect of that mastery – his great Agony in the Garden, done in response to a panel by his brother-in-law, lay behind him. It is hard, therefore, not to see the redoing of The Presentation of Christ in the Temple as some kind of contest as well as homage. But I found myself as I looked convinced that for Bellini what counted most was the opportunity, within the confines of someone else’s invention, to reflect on – to discover – what his own art most deeply consisted of. Oil paint versus tempera made many things clear. And, further, coming to terms with the true nature of one’s art – one’s necessary medium – meant coming closer to the mysteries enounced in Luke’s text.