Category: Recommended Reading

All That Was Solid

An interview with Adam Tooze in Jacobin:

An interview with Adam Tooze in Jacobin:

[I]f you think of the European Coal and Steel Community as the original kernel of the European integration project [in 1951], the whole project was to say, “We’ve got this tightly interconnected economic sector that has powerful geopolitical and broader historical implications, so we have to neutralize it. And the way we’re going to neutralize it is this mechanism.”

They did that with agriculture as well, in the early 1960s. They said, “Peasants are a big chunk of our population, a key part of this historical transformation, and politically potentially really lethal, and so as we stabilize, let’s have this Common Agricultural Policy.”

It’s really telling to me that before the 2008 crisis the Europeans were unable politically to draw on that and say, “Right, we’re building this tightly interconnected economic sector — finance. It has potentially explosive implications for the eurozone project. Clearly, we need to have a banking union, and we need to have it straight away and right from the beginning.”

More here.

How Liberalism Failed

Sheri Berman in Dissent:

Sheri Berman in Dissent:

A massive amount of ink has already been spilled trying to figure out what has gone wrong, but two narratives can be plucked from the confusion. The first focuses on economic change. Over the past few decades growth has slowed, inequality has risen, and social mobility has declined, particularly in the United States. This has made life more insecure for the working and middle classes by privileging highly educated and urban dwellers over less-educated and rural ones, and spreading economic risk, fear of the future, and social divisions throughout Western societies. The second narrative focuses on social change. During this same period, traditional norms and attitudes about religion, sexuality, family life, and more have been challenged by the emergence of feminist, LGBTI, and other social movements. Meanwhile, massive immigration and (especially in the United States) the mobilization of hitherto oppressed minority groups like African Americans has disrupted existing status and political hierarchies, making many white citizens in particular uncomfortable, resentful, and angry.

Most analysis stops here, at viewing economic or social change or some combination of the two as leading inevitably to dissatisfaction with liberal democracy and a readiness to embrace populist, illiberal, or even undemocratic alternatives. The issue, of course, is that social, economic, and technological change alone are not the problem—they only become so if politicians and governments don’t help citizens adjust to them. If we want, therefore, to understand liberal democracy’s current problems, we need to examine not only such changes, but also how elites and governments have responded to them.

More here.

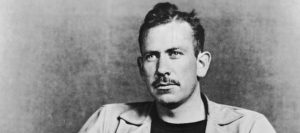

To understand Trump’s America, read John Steinbeck

Daniel Rey in New Statesman:

His book is a lie, a black, infernal creation of a twisted, distorted mind.” It was a Democratic representative from Oklahoma who gave this verdict of The Grapes of Wrath, John Steinbeck’s chronicle of migrants leaving the Dust Bowl for California. Disdained by the political elite and much of the literary set, it was nonetheless the best-selling book of 1939. Today’s parallels with the 1930s give Steinbeck’s work renewed urgency. He writes about farm labourers, shopkeepers and the denizens of village taverns – the kinds of people who, before the enormous political upheaval of 2016, the chattering classes barely remembered. In the age of Trump, mass-migration and the phenomenon of the ‘left behind’, Steinbeck’s work is just as relevant as when he wrote it. But more than that: reading Steinbeck fifty years after his death is the perfect antidote to the culture war that has gripped America.

His book is a lie, a black, infernal creation of a twisted, distorted mind.” It was a Democratic representative from Oklahoma who gave this verdict of The Grapes of Wrath, John Steinbeck’s chronicle of migrants leaving the Dust Bowl for California. Disdained by the political elite and much of the literary set, it was nonetheless the best-selling book of 1939. Today’s parallels with the 1930s give Steinbeck’s work renewed urgency. He writes about farm labourers, shopkeepers and the denizens of village taverns – the kinds of people who, before the enormous political upheaval of 2016, the chattering classes barely remembered. In the age of Trump, mass-migration and the phenomenon of the ‘left behind’, Steinbeck’s work is just as relevant as when he wrote it. But more than that: reading Steinbeck fifty years after his death is the perfect antidote to the culture war that has gripped America.

As in the 1930s, machinery – today it’s automation – threaten traditional livelihoods and ways of life in the United States. The Rust Belt is today’s version of the Dust Bowl of the Depression. “One man on a tractor can take the place of twelve or fourteen families,” representatives of city-based corporations explain to the tenant families working the Oklahoma land in The Grapes of Wrath. Unconcerned by the fabric of local communities, the agents suggest the families abandon their homes. “Why don’t you go west to California? … You can reach out anywhere and pick an orange,” they advise, incentivising migration, like the local authorities today who pack homeless people on buses and send them to other American cities.

More here.

It’s Cold, Dark and Lacks Parking. But Is This Finnish Town the World’s Happiest?

Patrick Kingsley in The New York Times:

Jan Mattlin was having what counts as a bad day in Kauniainen. He had driven to the town’s train station and found nowhere to park. Mildly piqued, he called the local newspaper to suggest a small article about the lack of parking spots. To Mr. Mattlin’s surprise, the editor put the story on the front page. “We have very few problems here,” recalled Mr. Mattlin, a partner at a private equity firm. “Maybe they didn’t have any other news available.” Such is the charmed life in Kauniainen (pronounced: COW-nee-AY-nen), a small and wealthy Finnish town that can lay claim to being the happiest place on the planet. Finland was named the world’s happiest country by the United Nations Sustainable Development Solutions Network in April, based on polling results from 156 nations. And a second survey found that Kauniainen’s 9,600 residents were the most satisfied in Finland, leading the local mayor, Christoffer Masar, to joke that theirs was the happiest town on earth.

Jan Mattlin was having what counts as a bad day in Kauniainen. He had driven to the town’s train station and found nowhere to park. Mildly piqued, he called the local newspaper to suggest a small article about the lack of parking spots. To Mr. Mattlin’s surprise, the editor put the story on the front page. “We have very few problems here,” recalled Mr. Mattlin, a partner at a private equity firm. “Maybe they didn’t have any other news available.” Such is the charmed life in Kauniainen (pronounced: COW-nee-AY-nen), a small and wealthy Finnish town that can lay claim to being the happiest place on the planet. Finland was named the world’s happiest country by the United Nations Sustainable Development Solutions Network in April, based on polling results from 156 nations. And a second survey found that Kauniainen’s 9,600 residents were the most satisfied in Finland, leading the local mayor, Christoffer Masar, to joke that theirs was the happiest town on earth.

…Kauniainen’s blandly named Adult Education Center, a tall building on the edge of town, did not sound promising. But it was here, not the bar, where large numbers of residents were having fun that evening. In the basement, they were weaving carpets on vast looms, and making pottery. On the ground floor, a choir was singing. On the floors above, others were painting replicas of Orthodox Christian icons — or practicing yoga. Subsidized by both the state and the city, the center offers cheap evening classes to residents “in basically anything that people might be interested in,” said Roger Renman, the center’s director.

More here.

Monday, December 24, 2018

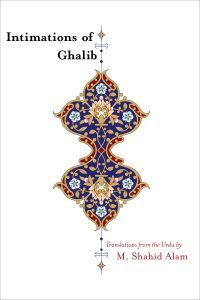

Imperfect Intimations: A Review of “Intimations of Ghalib” by M. Shahid Alam

by Ali Minai

Note: Translations in italics are literal translations by the reviewer, whereas those in bold italics are by the M. Shahid Alam in the book under review.

In reviewing “Intimations of Ghalib”, a new translation of selected ghazals of the Urdu poet Ghalib by M. Shahid Alam, let it be said at the outset that translating classical Urdu ghazal into any language – possibly excepting Persian – is an almost impossible task, and translating Ghalib’s ghazals even more so. The use of symbolism, the aphoristic aspect of each couplet, the frequent play on words, and the packing of multiple meanings into a single verse are all too easy to lose in translation. And no Urdu poet used all these devices more pervasively and subtly than Ghalib, and even learned scholars can disagree strongly on the “correct” meaning of particular verses. As such, Alam set himself an impossible task, and the result is, among other things, a demonstration of this.

In reviewing “Intimations of Ghalib”, a new translation of selected ghazals of the Urdu poet Ghalib by M. Shahid Alam, let it be said at the outset that translating classical Urdu ghazal into any language – possibly excepting Persian – is an almost impossible task, and translating Ghalib’s ghazals even more so. The use of symbolism, the aphoristic aspect of each couplet, the frequent play on words, and the packing of multiple meanings into a single verse are all too easy to lose in translation. And no Urdu poet used all these devices more pervasively and subtly than Ghalib, and even learned scholars can disagree strongly on the “correct” meaning of particular verses. As such, Alam set himself an impossible task, and the result is, among other things, a demonstration of this.

But first the positive – and there is much. The translator has made an admirable decision to retain the couplet structure of the ghazal in all translations, and in some cases, rhyme and refrain as well. In doing this, he has often succeeded in capturing the flavor of the ghazal genre, which is defined by strict rules of form, as described in the book’s Introduction. And even where he has struggled as a translator – indeed, often most in those places – Alam has succeeded more as a poet. Ultimately, the best part of this book is its intellectually honest and diligent attempt to grapple with its difficult task. In the process, Alam succeeds in creating a valuable work of literature that many readers should find accessible and enjoyable.

Before getting to the translations, the reader must read through the translator’s Introduction, which introduces both Ghalib and the genre of ghazal simply and elegantly. Mirza Asadullah Khan (1797-1869) – better known by his nom de plume, Ghalib – is generally regarded as one of the two or three greatest poets in the rich literary tradition of Urdu poetry. He lived in “interesting” times and at the center of calamitous events. Associated with the court of the last Mughal emperor, Bahadur Shah Zafar – an emperor in name only – Ghalib saw even that nominal glory go up in smoke during the rebellion of 1857, which led to the final British takeover of India and the end of the Mughal period. In the aftermath, Ghalib saw his own prospects diminished, many of his friends executed or exiled, and his world destroyed by forces he barely understood. In both his poetry and in his marvelous corpus of letters that are regarded as masterpiece of Urdu prose, Ghalib was able to create a persona and an ethos that is simultaneously individualistic, irreverent, complex, long-suffering and – paradoxically – good humored. His poetry, which is the focus of the book under review, is famous for both its philosophical depth and its Shakespearean insight into human nature. Read more »

Flawed Foundations: Britain’s Country Houses

by Adele A Wilby

Britain’s large country houses are original and distinctive, and they can be seen gracing the landscape from prime positions in the countryside. They are admired for their many features: their elegant architecture, the artistic treasures they house, the curatorial opportunities they offer, their landscaped gardens and grounds, and their representation of British genteel living. However, despite the obvious elegance of these houses, my response to them has usually been to view them in terms of, at worst, expressions of the British class system, and gross inequalities of wealth, power and privilege, and at best, as monuments to the skills of the tradesmen responsible for the construction of those houses. But Martin Belam’s article ‘Glasgow University to Make Amends Over Slavery Profits of the Past’ (Guardian Sept 17, 2018) was to change all that. It sent me on a reading journey that ended in me rethinking the representation of those iconic features of Britain’s countryside.

Belam’s article is a commentary on the ‘Slavery, Abolition and the University of Glasgow’ report (Mullen Newman 2018). The report acknowledges the University’s pride in its history of opposition to the transatlantic slave trade, the institution of slavery, and the involvement of many of its alumni in the abolitionist movement. However, the report concluded that ‘although the University of Glasgow never owned enslaved people or traded in goods they produced, it is nonetheless clear that the University received significant gifts and support from people who derived some or occasionally much of their wealth from slavery’, particularly in the West Indies during the 18thand 19thcenturies. The value of the financial endowments and prizes to the University runs into tens of millions of pounds, depending on how the amount is calculated in the present-day. The findings have prompted the University to commit to the implementation of a ‘Programme of reparative justice’.

The Glasgow University’s willingness to engage with the darker side of its history is admirable, and it is to be hoped that more institutions will follow suit and make known the origins of the financial contributions received during that period of British history, and embark on their own strategies of reparative justice should they need to do so. The findings in the report have also added to our existing knowledge of the relationship between wealth created from the enslavement of peoples and the establishment of institutions in Britain. Read more »

On Not Knowing: What Cause There Is for Caroling

by Emily Ogden

So little cause for carolings

Of such ecstatic sound

Was written on terrestrial things

Afar or nigh around,

That I could think there trembled through

His happy good-night air

Some blessed Hope, whereof he knew

And I was unaware.

—Thomas Hardy, “The Darkling Thrush,” 1900

The year and the century are dying; everything else is already dead. In Thomas Hardy’s “The Darkling Thrush” (1900), it is a dim day in the dimmest part of the year. Sunset will come early; night in Dorset, England, where Hardy lived, will last sixteen hours. A thrush sings, unwarrantably, of “joy illimited.” Why in the world? Or is his reason not of this world? Is he better informed than we? May we hope? Hardy’s subject is the close relationship between our own ignorance and our belief in another’s knowledge. To realize that we don’t know something is to realize that someone else might. To think that what the other knows might be good, might even be divine good, in spite of the earth’s sorry state—well, that is to celebrate Christmas.

“The Darkling Thrush” was first published on December 29, 1900, under the title “By the Century’s Deathbed.” There is a horticultural term for the season Hardy was then living at his house in Dorset, and that we in the Northern hemisphere are living now: the Persephone Days, named for the goddess of spring’s annual rape at Hades’ hands. You are in the Persephone Days, according to gardener Eliot Coleman, when fewer than ten of the twenty-four hours are light. Why ten hours? Because vegetables mostly slow or stop their growth with any less. “The ancient pulse of germ and birth / [is] shrunken hard and dry,” as Hardy wrote. Plenty of vegetables are cold tolerant. I have kale plants in my front yard now that can withstand a 10º F night. Darkness, however, stunts them. The problem winter poses for our survival is not the freezing of water. It’s the freezing of time. I’ll eat only what reaches maturity before the annual darkness comes.

Or I can always go to Whole Foods. Shopping and other glamours flurry about in the foreground these dark days, distracting us from Sol’s deadly swing toward Capricorn. Black Friday roughly coincides with the start of the Persephone Days; in Norfolk, Virginia (36.8º N latitude), they coincide exactly. Black Friday is itself a kind of heretical outgrowth from Advent, a time of holy anticipation; some of us confusedly observe them both by receiving toy catalogs, letting ourselves buy cheese balls from festive displays, and growing tired of ecstatic carolings. Call it Advert. If you were in America four weeks ago, you may have found the retail festival the most noticeable of the three, followed by the liturgical holiday, with the horticultural one coming in a distant third, if at all. But that’s the whole point of the first two: to be noticeable. So as not to notice the other thing. The very intensity of the annual danse macabre shows we have not entirely forgotten our fear of the dark. Read more »

This Year On Earth

by Mary Hrovat

In 2018, Earth picked up about 40,000 metric tons of interplanetary material, mostly dust, much of it from comets. Earth lost around 96,250 metric tons of hydrogen and helium, the lightest elements, which escaped to outer space. Roughly 505,000 cubic kilometers of water fell on Earth’s surface as rain, snow, or other types of precipitation. Bristlecone pines, which can live for millennia, each gained perhaps a hundredth of an inch in diameter. Countless mayflies came and went. As of this writing, more than one hundred thirty-six million people were born in 2018, and more than fifty-seven million died.

In 2018, Earth picked up about 40,000 metric tons of interplanetary material, mostly dust, much of it from comets. Earth lost around 96,250 metric tons of hydrogen and helium, the lightest elements, which escaped to outer space. Roughly 505,000 cubic kilometers of water fell on Earth’s surface as rain, snow, or other types of precipitation. Bristlecone pines, which can live for millennia, each gained perhaps a hundredth of an inch in diameter. Countless mayflies came and went. As of this writing, more than one hundred thirty-six million people were born in 2018, and more than fifty-seven million died.

Tidal interactions are very slowly increasing the distance between Earth and the moon, which ended 2018 about 3.8 centimeters further apart than they were at the beginning. As a consequence, Earth is now rotating slightly more slowly; the day is a tiny fraction of a second longer. Earth and the sun are also creeping apart, by around 1.5 centimeters per year, although the effect of tidal interactions is very small. Most of the change is due to changes in the sun’s gravitational pull as it converts some of its mass into energy by nuclear fusion.

The entire solar system traveled roughly 7.25 billion kilometers in its orbit about the center of the Milky Way. This vast distance, however, is only about 1/230,000,000th of the entire orbit.

In 2018, there were two lunar eclipses and three partial solar eclipses, each a step in the long gravitational dance making up the roughly 18-year saros cycle. During one saros cycle, eclipses with particular characteristics (partial, total, annular) and a specific Earth–Moon–Sun geometry occur in a predictable sequence; at the end, the whole thing starts again. This pattern has been repeating for much longer than humans have been around to see it.

I like knowing these bits of cosmic context because they link me to a larger world. I can echo the words of Ptolemy: “Mortal as I am, I know that I am born for a day. But when I follow at my pleasure the serried multitude of the stars in their circular course, my feet no longer touch the earth.” Read more »

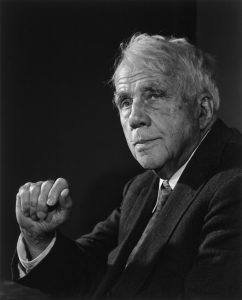

Discovering Robert Frost

by Joshua Wilbur

In college, I took a course on American poetry, but I missed the class on Robert Frost. To be honest, I slept straight through it. That particular winter was brutally cold. I lived in a worn-out house some fifteen minutes from campus, and the water heater in the basement was broken. So I skipped the ice-cold shower at 8AM, the wet walk through a foot of snow, and the monotone reading of a few representative poems by a long-tenured professor. I stayed in my warm bed, wrapped up in the comforter.

From that morning until only a few weeks ago, my mental image of Robert Frost was that of a grey-haired, folksy New Englander who wrote modest poems about country life. I knew “The Road Not Taken,” though I didn’t understand it. I was familiar with a handful of other titles— “Fire and Ice,” “Mending Wall,” “Stopping By Woods on a Snowy Evening”— but I can’t say if I had ever really read these poems. If so, they hardly made an impression on me. In short, I had Frost figured as a quaint poet of nature, a leftover from 19th Century America.

I now realize that I was wonderfully mistaken, that Robert Frost isn’t what he seems, and that the fundamental experience of reading Frost is discovering that the poems aren’t what they seem. Harold Bloom has called Frost a “trickster and a mischief maker.” In The New Yorker, Joshua Rothman describes Frost’s “poetic sleight of hand,” his characteristic tendency for deception. In his own words, Frost considered poetry “the one permissible way of saying one thing and meaning another.” For nearly fifty years, the poet hid ulterior meanings behind plain language. Read more »

n + 1 Types: Atheism and Historical Awareness

by Jeroen Bouterse

It is simultaneously awkward and exciting to read about your own consciously and responsibly adopted beliefs as something to be anatomized. It is also something atheists are not always much disposed to. On the contrary, perhaps: many forms of atheism present themselves as a consequence of free thought, of emancipation from tradition. The internal logic of their arguments prescribes that while religious beliefs, being non-rational, are in need of cultural or psychological explanation, atheism is really just what you will gravitate towards once you finally start thinking. One question here will be whether this is necessarily the case.

It is simultaneously awkward and exciting to read about your own consciously and responsibly adopted beliefs as something to be anatomized. It is also something atheists are not always much disposed to. On the contrary, perhaps: many forms of atheism present themselves as a consequence of free thought, of emancipation from tradition. The internal logic of their arguments prescribes that while religious beliefs, being non-rational, are in need of cultural or psychological explanation, atheism is really just what you will gravitate towards once you finally start thinking. One question here will be whether this is necessarily the case.

Most Atheists Just Don’t Get It

To the extent that what I just said is a recognizable self-description, we deserve the injustice that John Gray does to us in his Seven Types of Atheism (2018). Of the seven types Gray distinguishes, only two – its more withdrawn, Epicurean or mystical manifestations – get a positive review. One other version (‘God-haters’) is interesting but also confused, hardly atheistic, and of course evil. The remaining four types are primarily variations upon the theme of the naive progressivist: people who think they have left behind monotheistic religion, but who have in fact replaced it with a new God: humanity, or some proxy to humanity – science, or progress, or Enlightenment, or secular political utopia.

Idolizing or deifying something while claiming to be an atheist requires some self-delusion, according to Gray, and he readily psychologizes this phenomenon. Atheists’ understanding of religion has been “unthinkingly” inherited from monotheism (5); new atheists are “unwitting disciplines” of Comte’s positivism (11); twenty-first-century atheists are “unthinking liberals” (20); secular thinkers have continued to try to harmonize Jewish and Greek views of the world “without knowing what they are doing” (29).

A charitable reading of this is that Gray is not pointing out lack of cognitive capacity, but lack of historical awareness. Read more »

Trademarks and Language

by Gabrielle C. Durham

Certain phrases choke us with their ubiquity at some point:

Certain phrases choke us with their ubiquity at some point:

- “Just do it.” (Nike)

- “Let’s get ready to rumble!” (Sports announcer Michael Buffer)

- “That’s hot.” (Paris Hilton)

- “Hasta la vista, baby.” (“Terminator 2: Judgment Day,” as delivered by Arnold Schwarzenegger)

Did you know these have all been trademarked? This means that you are supposed to have the owner’s permission to use any one of these phrases. These sentences were so popular at some time in history that their crafters applied to trademark and thereby protect the specific saying.

A trademark is any name, symbol, figure, letter, word, mark (such as the Nike Swoosh), or other device that is used by a manufacturer or a merchant to identify and promote a specific good or service and differentiate it from other similar goods or services from a competing manufacturer or dealer. Once you register a trademark, it is yours. You own it. In the United States, it is registered with the Patent and Trademark Office and only you can enjoy the exclusive use of your trademark. The word “trademark” was first recorded in the mid-16th century. (Property rights go way back in law; you could make the argument that they are the reason that laws arose.) Read more »

Well, Hello, Dolly

by Thomas O’Dwyer

A pretty doll in a box at the foot of the bed – what could make a better Christmas morning for a little girl?

“Aaw, she’s so pretty.” The doll promised happy days to come – hair to brush and style, outfits to make and match, private chats to be had. Good chats, with someone who only listened, never talked. A doll was the essence of childhood for millions of young girls over centuries, even millennia. A toy became a baby, a little sister or even a “little me”. The doll was a simple thing until the middle of the last century but alas, it is no longer, like childhood itself.

“You can’t find toys like that anymore,” say the oldsters about their memories of playthings. In reality, grumbling adults are indifferent to such things, unless they are collectors. To children, toys and dolls are as new and exciting as they have ever been. We may think modern dolls have morphed into figures of complexity, controversy and even creepiness. They have become trend setters, celebrities and psychotic misfits – analysed, criticised, rarely praised. Are dolls still loved? Are they innocent companions – or sexist props, propagandists for adulthood, training aids for womanhood?

It is narcissistic, this human urge to fashion models of ourselves, and it’s quite ancient. In prehistory, dolls represented some aspect of religion. Gods themselves are invisible dolls, fashioned in the human image and likeness. Early dolls were fetishes. The origin of this word was in sorcery, charms and spells, exposing the purpose of dolls. The fetish differs from an idol in that it is worshipped for itself, not as a representative of an invisible spirit. Read more »

An Ode To Joy

by Max Sirak

As we approach the end of the year, it’s that time again. Not to flip the page to the next month, but to buy a new calendar. (Who am I kidding? It’s probably only me and your grandmother who still uses paper wall calendars…) And also to reflect.

As we approach the end of the year, it’s that time again. Not to flip the page to the next month, but to buy a new calendar. (Who am I kidding? It’s probably only me and your grandmother who still uses paper wall calendars…) And also to reflect.

I learned a lot in 2018. I learned about how the genealogy of Batman can be traced to Alexander Dumas. I learned about the importance of taking ownership of our emotional reactions. But, by far, the most important thing I learned was the importance of not growing up.

Say What?

It’s not that I have anything against being an adult. Working, making money, buying stuff, and maybe owning the place you live are all fine and good, I guess. But after doing these things for a while, I realized I was feeling pretty empty inside.

These things, which mean so much to so many and most seem to organize their lives around, didn’t do it for me. They didn’t satisfy me. And the more I tried to fake it, the more I tried to buy in and force myself to care about these things that practically everyone else seemed to be completely absorbed in – the worse I felt.

Until one night, toward the beginning of September, when I stumbled back into joy. Read more »

Callous Doughboy’s Band: Part 2

by Christopher Bacas

Guinea and Redhead were part of a large food chain. Beyond campus’ freshly-baked sidewalks, a Cowboy Mafia ferried contraband from the south. They landed small prop planes on ranch land outside of town, cut powder with dental anesthetics and broke up the bales. Their wares clumped on our cafeteria trays and glinted in tiny screw-top bottles. The capo, a local big-hat business man,who ran a palatial kicker-dance hall and owned the ranch. That legit business and his crew’s discipline kept them out of jail. Maybe a hat full of cash in the bargain.

Guinea and Redhead were part of a large food chain. Beyond campus’ freshly-baked sidewalks, a Cowboy Mafia ferried contraband from the south. They landed small prop planes on ranch land outside of town, cut powder with dental anesthetics and broke up the bales. Their wares clumped on our cafeteria trays and glinted in tiny screw-top bottles. The capo, a local big-hat business man,who ran a palatial kicker-dance hall and owned the ranch. That legit business and his crew’s discipline kept them out of jail. Maybe a hat full of cash in the bargain.

My Trumpet buddy shared an apartment in a low-rise student complex. Trumpet’s Roomie was in with the Cowboys. I found out when I made a visit. From outside, the shitty drywall construction leaked sound and odors like a window screen. Inside, eucalyptus gas wrapped around my head. I knew Roomie a little. He didn’t seem to remember. Wide-eyed, fidgeting, he appraised me.

“You cool?”

I reckoned I was. In his bedroom, he kicked aside some laundry and slid open a door. On the floor, a bulging black Hefty bag yawned. Inside, Tolkein magic: lichen grown thigh-deep, whispering in shadow. Despite mind-expanding potential, there was no joy in babysitting a large ingot of fools’ gold. Read more »

Sunday, December 23, 2018

How to brain hack your New Year’s resolution for success

Kevin Dickinson in Big Think:

The new year approaches and with it comes our annual habit of self-promises in the form of New Year’s resolutions. Statistically speaking, though, 2019 won’t be your year. While many of us start strong, we tend to flounder come February, and studies cite the failure rate to be anywhere from 80 to 90 percent.

The new year approaches and with it comes our annual habit of self-promises in the form of New Year’s resolutions. Statistically speaking, though, 2019 won’t be your year. While many of us start strong, we tend to flounder come February, and studies cite the failure rate to be anywhere from 80 to 90 percent.

In the face of those odds, many have grown despondent at the idea that a New Year’s resolution can make a difference and choose not to make one. But that doesn’t help much either. A notable study in the Journal of Clinical Psychology, published in 2002, found that New Year’s resolvers — people who actually tried to fix things — reported a higher rate of success in changing a life problem, than “nonresolvers.” Only 4 percent of the latter group managed that feat.

The study noted that the “successful resolvers employed more cognitive-behavioral processes” than the nonresolvers or, as they are more commonly known, “brain hacks.”

More here.

The Miseducation of Sheryl Sandberg

Duff McDonald in Vanity Fair:

The ongoing three-way public-relations car wreck involving Washington, Facebook, and Sheryl Sandberg, the company’s powerful C.O.O., begs a question of America’s esteemed managerial class. How has someone with such sterling Establishment credentials—Harvard University, Harvard Business School, the Clinton administration—managed to find herself in such a pickle?

The ongoing three-way public-relations car wreck involving Washington, Facebook, and Sheryl Sandberg, the company’s powerful C.O.O., begs a question of America’s esteemed managerial class. How has someone with such sterling Establishment credentials—Harvard University, Harvard Business School, the Clinton administration—managed to find herself in such a pickle?

The answer won’t be found in the minutes of Facebook board meetings or in Sandberg’s best-selling books, Lean In and Option B, which cemented her position in the corporate firmament as a feminist heroine. Rather, it starts all the way back in 1977, when Sandberg was just eight years old and the U.S. economy was still recovering from the longest and deepest recession since the end of World War II. That’s the year that Harvard Business School professor Abraham Zaleznik wrote an article entitled, “Managers and Leaders: Are They Different?” in America’s most influential business journal, Harvard Business Review. For years, Zaleznik argued, the country had been over-managed and under-led. The article helped spawn the annual multi-billion-dollar exercise in nonsense known as the Leadership Industry, with Harvard as ground zero. The article gave Harvard Business School a new raison d’être in light of the fact that the product it had been selling for decades—managers—was suddenly no longer in vogue. Henceforth, it would be molding leaders.

More here.

Barack Obama Goes All In Politically to Fight Gerrymandering

Edward-Isaac Dovere in The Atlantic:

Barack Obama has sometimes struggled to find his political footing since leaving office, even though he’s more popular and more in demand by Democrats than at any point since 2008. He’d been challenged by a very deliberate decision he’d made to steer clear of direct confrontation with Donald Trump for a year and a half, aware that a fight is always exactly what Trump is looking for. Why help him turn out the Republican base?

Behind the scenes, Obama had been much more active and forceful, meeting with top Democrats and mentoring up-and-coming Democrats, including most of the expected 2020 presidential candidates. Then, in September, he unleashed an intense argument against Trump and carried that forward with considerable effect through the midterms, which produced a blue wave that devastated Republicans nationally and locally. But since then, he’s been eager to move past the Trump dynamic again and address bigger, less personal politics.

The answer he’s found to accomplish this: redistricting reform.

More here.

The Nobel Prize for Climate Catastrophe

Jason Hickel in Foreign Policy:

Many people were thrilled when they heard that the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics this year went to William Nordhaus of Yale University, a man known for his work on climate change. Finally, the economics profession is giving climate the attention it deserves, just as the world is waking up to the severity of our ecological emergency. Media outlets have taken this positive narrative and run with it.

But while Nordhaus may be revered among economists, climate scientists and ecologists have a very different opinion of his legacy. In fact, many believe that the failure of the world’s governments to pursue aggressive climate action over the past few decades is in large part due to arguments that Nordhaus has advanced.

It’s a blazing controversy that hinges on the single most consequential issue in climate economics: the question of growth. The stakes couldn’t be higher. After all, this isn’t just a matter of abstract academic debate; the future of human civilization hangs in the balance.

More here.