James McAuley and Greil Marcus, and a reply by Mark Lilla in the New York Review of Books:

James McAuley and Greil Marcus, and a reply by Mark Lilla in the New York Review of Books:

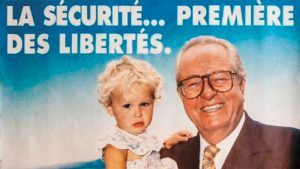

“Something new is happening on the European right, and it involves more than xenophobic outbursts,” Lilla writes. But in many cases, xenophobia is far from peripheral. The hatred of migrants and foreigners is the essence of the pitch that the contemporary European right has made to voters. How else do we explain the tendency of right-wing parties across the continent to focus on a so-called “invasion” of migrants, even as their numbers continue to fall? Arrivals are down to their lowest levels since 2015, when Europe experienced a historic influx of migrants and refugees that triggered a political crisis with no apparent end in sight. The leaders of far-right and, now, mainstream conservative parties across the continent are focusing squarely on immigration and the alleged threat to national identity it poses. In many cases, the rhetorical line between “right” and “far right” is increasingly difficult to delineate.

This is exactly the climate that has enabled the rise of Marion Maréchal—formerly Marion Maréchal-Le Pen—the twenty-nine-year-old scion of France’s, and probably Europe’s, best-known far-right dynasty. A darling of Steve Bannon, Maréchal addressed the Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) in Washington this past February. Lilla quotes Maréchal’s remarks in that speech extensively, as ostensible evidence of a new intellectual movement among a younger generation of European conservatives. But he selectively omits other lines from that same speech, which clearly situate Maréchal in a right wing terrified by the prospect of a white majority apparently under siege. “After forty years of massive immigration, Islamic lobbies and political correctness,” she said at CPAC, “France is in the process of passing from the eldest daughter of the Catholic Church to the little niece of Islam, and the terrorism is only the tip of the iceberg.” Given that Lilla quoted so much else of what she said, readers of The New York Review deserve to read the extreme words from a woman Lilla presents as both “calm and collected” and “intellectually inclined.” Her speech was also fundamentally dishonest: according to most available estimates, Muslims count for no more than 10 percent of the total French population.

More here.

WHEN

WHEN Just a few years ago Yuval Noah Harari was an obscure Israeli historian with a knack for playing with big ideas. Then he wrote Sapiens, a sweeping, cross-disciplinary account of human history that landed on the bestseller list and remains there four years later. Like Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs and Steel, Sapiens proposed a dazzling historical synthesis, and Harari’s own quirky pronouncements—“modern industrial agriculture might well be the greatest crime in history”— made for compulsive reading. The book also won him a slew of high-profile admirers, including Barack Obama, Bill Gates, and Mark Zuckerberg.

Just a few years ago Yuval Noah Harari was an obscure Israeli historian with a knack for playing with big ideas. Then he wrote Sapiens, a sweeping, cross-disciplinary account of human history that landed on the bestseller list and remains there four years later. Like Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs and Steel, Sapiens proposed a dazzling historical synthesis, and Harari’s own quirky pronouncements—“modern industrial agriculture might well be the greatest crime in history”— made for compulsive reading. The book also won him a slew of high-profile admirers, including Barack Obama, Bill Gates, and Mark Zuckerberg. But Einstein’s was a God of philosophy, not religion. When asked many years later whether he believed in God, he replied: ‘I believe in Spinoza’s God, who reveals himself in the lawful harmony of all that exists, but not in a God who concerns himself with the fate and the doings of mankind.’ Baruch Spinoza, a contemporary of Isaac Newton and Gottfried Leibniz, had conceived of God as identical with nature. For this, he was considered a dangerous

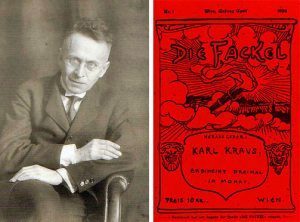

But Einstein’s was a God of philosophy, not religion. When asked many years later whether he believed in God, he replied: ‘I believe in Spinoza’s God, who reveals himself in the lawful harmony of all that exists, but not in a God who concerns himself with the fate and the doings of mankind.’ Baruch Spinoza, a contemporary of Isaac Newton and Gottfried Leibniz, had conceived of God as identical with nature. For this, he was considered a dangerous  Vienna as a bourgeois, democratic city was never a stable entity. The liberal bourgeoisie came to municipal power in Vienna in the 1860s, yet the authority of the monarchy and aristocracy persisted, though in a weakened form, and, unlike the partial integration of the bourgeoisie into the social world of the British and French aristocracy, it kept its doors barred to the newcomers. And almost as soon as the liberals gained a foothold, a third element asserted itself, a gathering din of nationalist agitations from the patchwork of ethnicities that constituted the Habsburg Empire, each growing restless in the dilapidating imperium. The Liberals, never fully in control, saw their influence hedged and threatened almost immediately.

Vienna as a bourgeois, democratic city was never a stable entity. The liberal bourgeoisie came to municipal power in Vienna in the 1860s, yet the authority of the monarchy and aristocracy persisted, though in a weakened form, and, unlike the partial integration of the bourgeoisie into the social world of the British and French aristocracy, it kept its doors barred to the newcomers. And almost as soon as the liberals gained a foothold, a third element asserted itself, a gathering din of nationalist agitations from the patchwork of ethnicities that constituted the Habsburg Empire, each growing restless in the dilapidating imperium. The Liberals, never fully in control, saw their influence hedged and threatened almost immediately. Anglo-Saxon London suffers from an image problem, or more precisely from the problem that we have no image of it at all. In contrast to the showy glamour of Roman Britain, with its amphitheatres, temples and abundance of literature, or the vibrant cultural melting pot of the Tudor era, the Anglo-Saxon metropolis has almost no remaining visible architecture, a dearth of written sources and a patchy archaeological presence.

Anglo-Saxon London suffers from an image problem, or more precisely from the problem that we have no image of it at all. In contrast to the showy glamour of Roman Britain, with its amphitheatres, temples and abundance of literature, or the vibrant cultural melting pot of the Tudor era, the Anglo-Saxon metropolis has almost no remaining visible architecture, a dearth of written sources and a patchy archaeological presence. Steven Strogatz in the NYT:

Steven Strogatz in the NYT:

Jeffrey J. Williams interviews Bruce Robbins over at the LA Review of Books:

Jeffrey J. Williams interviews Bruce Robbins over at the LA Review of Books:

Richard Marshall interviews Sander Verhaegh in 3:AM Magazine:

Richard Marshall interviews Sander Verhaegh in 3:AM Magazine: Dylan Riler in the New Left Review:

Dylan Riler in the New Left Review: Everything is formed by habit. The crow’s feet that come from squinting or laughter, the crease in a treasured and oft-opened letter, the ruts worn in a path frequently traveled—all are created by repeatedly performing the same action. Even neurons are formed by habit. When continuously exposed to a fixed stimulus, neurons become steadily less sensitive to that stimulus—until they eventually stop responding to it altogether. Anything that’s habitually encountered—the landscape of a daily commute, storefronts passed on a walk to the bus stop, photographs arranged on a mantelpiece—tends toward invisibility. The more we see a thing, the less we see it. Familiarity breeds neglect. Once perception settles into a comfortable pattern, we fall asleep to it. Only when the pattern is broken do we notice there is a pattern at all. The chains of mental habit are too weak to be felt until they are too strong to be broken, to paraphrase Samuel Johnson. Wit, whether visual or verbal, can make the commonplace uncommon again by breaking the habits that render perception routine. We tend to define the quality of wit as merely being deft with a clever comeback. But true wit is richer, cannier, more riddling. And the best of it is often based on a biological phenomenon called supernormal stimuli.

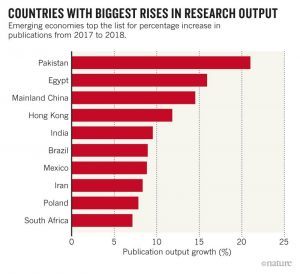

Everything is formed by habit. The crow’s feet that come from squinting or laughter, the crease in a treasured and oft-opened letter, the ruts worn in a path frequently traveled—all are created by repeatedly performing the same action. Even neurons are formed by habit. When continuously exposed to a fixed stimulus, neurons become steadily less sensitive to that stimulus—until they eventually stop responding to it altogether. Anything that’s habitually encountered—the landscape of a daily commute, storefronts passed on a walk to the bus stop, photographs arranged on a mantelpiece—tends toward invisibility. The more we see a thing, the less we see it. Familiarity breeds neglect. Once perception settles into a comfortable pattern, we fall asleep to it. Only when the pattern is broken do we notice there is a pattern at all. The chains of mental habit are too weak to be felt until they are too strong to be broken, to paraphrase Samuel Johnson. Wit, whether visual or verbal, can make the commonplace uncommon again by breaking the habits that render perception routine. We tend to define the quality of wit as merely being deft with a clever comeback. But true wit is richer, cannier, more riddling. And the best of it is often based on a biological phenomenon called supernormal stimuli. Emerging economies showed some of the largest increases in research output in 2018, according to estimates from the publishing-services company Clarivate Analytics. Egypt and Pakistan topped the list in percentage terms, with rises of 21% and 15.9%, respectively. China’s publications rose by about 15%, and India, Brazil, Mexico and Iran all saw their output grow by more than 8% compared with 2017 (See ‘Countries with biggest rises in research output’). Globally, research output rose by around 5% in 2018, to an estimated 1,620,731 papers listed in a vast science-citation database Web of Science, the highest ever (see ‘Research output rose again in 2018’). This diversification of players in science is a phenomenal success, says Caroline Wagner, a science and technology policy analyst at Ohio State University, and a former adviser to the US government. “In 1980, only 5 countries did 90% of all science — the United States, the United Kingdom, France, Germany and Japan,” she says. “Now there are 20 countries within the top producing group.”

Emerging economies showed some of the largest increases in research output in 2018, according to estimates from the publishing-services company Clarivate Analytics. Egypt and Pakistan topped the list in percentage terms, with rises of 21% and 15.9%, respectively. China’s publications rose by about 15%, and India, Brazil, Mexico and Iran all saw their output grow by more than 8% compared with 2017 (See ‘Countries with biggest rises in research output’). Globally, research output rose by around 5% in 2018, to an estimated 1,620,731 papers listed in a vast science-citation database Web of Science, the highest ever (see ‘Research output rose again in 2018’). This diversification of players in science is a phenomenal success, says Caroline Wagner, a science and technology policy analyst at Ohio State University, and a former adviser to the US government. “In 1980, only 5 countries did 90% of all science — the United States, the United Kingdom, France, Germany and Japan,” she says. “Now there are 20 countries within the top producing group.” Pablo Calvi in The Believer:

Pablo Calvi in The Believer:

Fara Dabhoiwala in The Guardian:

Fara Dabhoiwala in The Guardian: