Ellen Hendriksen in Scientific American:

Forward-thinking companies strive to be socially responsible. Beer commercials exhort us to drink responsibly. And every parent wants their kid to be more responsible. All in all, responsibility is a good thing, right? It is, until it’s not. What to do when you have too much of a good thing? This week, Savvy Psychologist Dr. Ellen Hendriksen offers four signs of over-responsibility, plus three ways to overcome it. Being a responsible person is usually a good thing—it means you’re committed, dependable, accountable, and care about others. It’s the opposite of shirking responsibility by pointing fingers or making excuses. But it’s easy to go too far. Do you take on everyone’s tasks? If someone you love is grumpy, do you assume it’s something you did? Do you apologize when someone bumps into you? Owning what’s yours—mistakes and blunders included—is a sign of maturity, but owning everybody else’s mistakes and blunders, not to mention tasks, duties, and emotions, is a sign of over-responsibility.

Forward-thinking companies strive to be socially responsible. Beer commercials exhort us to drink responsibly. And every parent wants their kid to be more responsible. All in all, responsibility is a good thing, right? It is, until it’s not. What to do when you have too much of a good thing? This week, Savvy Psychologist Dr. Ellen Hendriksen offers four signs of over-responsibility, plus three ways to overcome it. Being a responsible person is usually a good thing—it means you’re committed, dependable, accountable, and care about others. It’s the opposite of shirking responsibility by pointing fingers or making excuses. But it’s easy to go too far. Do you take on everyone’s tasks? If someone you love is grumpy, do you assume it’s something you did? Do you apologize when someone bumps into you? Owning what’s yours—mistakes and blunders included—is a sign of maturity, but owning everybody else’s mistakes and blunders, not to mention tasks, duties, and emotions, is a sign of over-responsibility.

But here’s the twist: being overly responsible isn’t just the realm of control freaks or earnest Eagle Scouts. Over-responsibility can work for you, building trust and even currying favor.

For example, a fascinating joint study out of Harvard Business School and Wharton examined what happens when we apologize in the absence of culpability—that is, when we take responsibility for something that’s clearly not our fault. Specifically, on a rainy day, the researchers hired an actor to approach travelers in a busy train station and ask to use their cell phones. Half the time, the actor led by taking responsibility for the weather: “I’m so sorry about the rain! Can I borrow your cell phone?” The other half of the time, he simply asked “Can I borrow your cell phone?” When he took responsibility for the weather, 47% of the travelers offered their phone. But when he simply asked, only 9% of the travelers acquiesced. The findings lined up with previous research showing that people who express guilt or regret are better liked than those who don’t. Why? Taking responsibility is a show of empathy. The apology isn’t necessarily remorseful; instead, it’s recognition of and concern for someone else’s experience.

More here.

In the animal world, monogamy has some clear perks. Living in pairs can give animals some stability and certainty in the constant struggle to reproduce and protect their young—which may be why it has evolved independently in various species. Now, an analysis of gene activity within the brains of frogs, rodents, fish, and birds suggests there may be a pattern common to monogamous creatures. Despite very different brain structures and evolutionary histories, these animals all seem to have developed monogamy by turning on and off some of the same sets of genes. “It is quite surprising,” says Harvard University evolutionary biologist Hopi Hoekstra, who was not involved in the new work. “It suggests that there’s a sort of genomic strategy to becoming monogamous that evolution has repeatedly tapped into.” Evolutionary biologists have proposed various

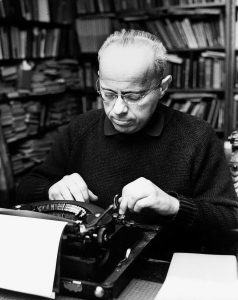

In the animal world, monogamy has some clear perks. Living in pairs can give animals some stability and certainty in the constant struggle to reproduce and protect their young—which may be why it has evolved independently in various species. Now, an analysis of gene activity within the brains of frogs, rodents, fish, and birds suggests there may be a pattern common to monogamous creatures. Despite very different brain structures and evolutionary histories, these animals all seem to have developed monogamy by turning on and off some of the same sets of genes. “It is quite surprising,” says Harvard University evolutionary biologist Hopi Hoekstra, who was not involved in the new work. “It suggests that there’s a sort of genomic strategy to becoming monogamous that evolution has repeatedly tapped into.” Evolutionary biologists have proposed various  The science-fiction writer and futurist Stanisław Lem was well acquainted with the way that fictional worlds can sometimes encroach upon reality. In his autobiographical essay “

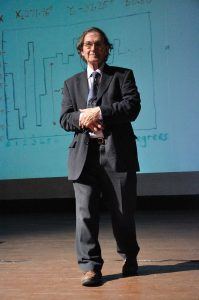

The science-fiction writer and futurist Stanisław Lem was well acquainted with the way that fictional worlds can sometimes encroach upon reality. In his autobiographical essay “ Sir Roger Penrose has had a remarkable life. He has contributed an enormous amount to our understanding of general relativity, perhaps more than anyone since Einstein himself — Penrose diagrams, singularity theorems, the Penrose process, cosmic censorship, and the list goes on. He has made important contributions to mathematics, including such fun ideas as the Penrose triangle and aperiodic tilings. He has also made bold conjectures in the notoriously contentious areas of quantum mechanics and the study of consciousness. In his spare time he’s managed to become an extremely successful author, writing such books as The Emperor’s New Mind and The Road to Reality. With far too much that we could have talked about, we decided to concentrate in this discussion on spacetime, black holes, and cosmology, but we made sure to reserve some time to dig into quantum mechanics and the brain by the end.

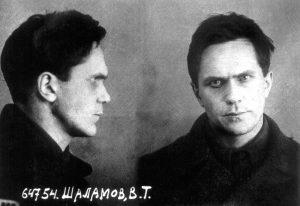

Sir Roger Penrose has had a remarkable life. He has contributed an enormous amount to our understanding of general relativity, perhaps more than anyone since Einstein himself — Penrose diagrams, singularity theorems, the Penrose process, cosmic censorship, and the list goes on. He has made important contributions to mathematics, including such fun ideas as the Penrose triangle and aperiodic tilings. He has also made bold conjectures in the notoriously contentious areas of quantum mechanics and the study of consciousness. In his spare time he’s managed to become an extremely successful author, writing such books as The Emperor’s New Mind and The Road to Reality. With far too much that we could have talked about, we decided to concentrate in this discussion on spacetime, black holes, and cosmology, but we made sure to reserve some time to dig into quantum mechanics and the brain by the end. For fifteen years the writer Varlam Shalamov was imprisoned in the Gulag for participating in “counter-revolutionary Trotskyist activities.” He endured six of those years enslaved in the gold mines of Kolyma, one of the coldest and most hostile places on earth. While he was awaiting sentencing, one of his short stories was published in a journal called Literary Contemporary. He was released in 1951, and from 1954 to 1973 he worked on Kolyma Stories, a masterpiece of Soviet dissident writing that has been newly translated into English and published by New York Review Books Classics this week. Shalamov claimed not to have learned anything in Kolyma, except how to wheel a loaded barrow. But one of his fragmentary writings, dated 1961, tells us more.

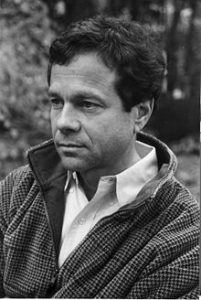

For fifteen years the writer Varlam Shalamov was imprisoned in the Gulag for participating in “counter-revolutionary Trotskyist activities.” He endured six of those years enslaved in the gold mines of Kolyma, one of the coldest and most hostile places on earth. While he was awaiting sentencing, one of his short stories was published in a journal called Literary Contemporary. He was released in 1951, and from 1954 to 1973 he worked on Kolyma Stories, a masterpiece of Soviet dissident writing that has been newly translated into English and published by New York Review Books Classics this week. Shalamov claimed not to have learned anything in Kolyma, except how to wheel a loaded barrow. But one of his fragmentary writings, dated 1961, tells us more. My students and I were in the midst of studying Learning from Las Vegas when the news came of Robert Venturi’s death. We had just absorbed an extraordinary lecture tour of his mother’s house, in all its faux–New England simplicity, which harbored so many allusive surprises; now the book, published in 1972, was revealing itself to be a profoundly American source for the cultural-studies movement whose genealogy we had for so long attributed to the Birmingham School. It also turns out to have been one of the underground blasts that signaled the beginning of postmodernism.

My students and I were in the midst of studying Learning from Las Vegas when the news came of Robert Venturi’s death. We had just absorbed an extraordinary lecture tour of his mother’s house, in all its faux–New England simplicity, which harbored so many allusive surprises; now the book, published in 1972, was revealing itself to be a profoundly American source for the cultural-studies movement whose genealogy we had for so long attributed to the Birmingham School. It also turns out to have been one of the underground blasts that signaled the beginning of postmodernism. The grand term ‘intellectual property’ covers a lot of ground: the software that runs our lives, the movies we watch, the songs we listen to. But also the credit-scoring algorithms that determine the contours of our futures, the chemical structure and manufacturing processes for life-saving pharmaceutical drugs, even the golden arches of McDonald’s and terms such as ‘Google’. All are supposedly ‘intellectual property’. We are urged, whether by stern warnings on the packaging of our Blu-ray discs or by sonorous pronouncements from media company CEOs, to cease and desist from making unwanted, illegal or improper uses of such ‘property’, not to be ‘pirates’, to show the proper respect for the rights of those who own these things. But what kind of property is this? And why do we refer to such a menagerie with one inclusive term?

The grand term ‘intellectual property’ covers a lot of ground: the software that runs our lives, the movies we watch, the songs we listen to. But also the credit-scoring algorithms that determine the contours of our futures, the chemical structure and manufacturing processes for life-saving pharmaceutical drugs, even the golden arches of McDonald’s and terms such as ‘Google’. All are supposedly ‘intellectual property’. We are urged, whether by stern warnings on the packaging of our Blu-ray discs or by sonorous pronouncements from media company CEOs, to cease and desist from making unwanted, illegal or improper uses of such ‘property’, not to be ‘pirates’, to show the proper respect for the rights of those who own these things. But what kind of property is this? And why do we refer to such a menagerie with one inclusive term? For all its economic might, Germany’s main centrist parties are

For all its economic might, Germany’s main centrist parties are  The latest TV series by charming, tidy-up guru Marie Kondo

The latest TV series by charming, tidy-up guru Marie Kondo  A deep-learning algorithm is helping doctors and researchers to pinpoint a range of rare genetic disorders by analysing pictures of people’s faces. In a paper

A deep-learning algorithm is helping doctors and researchers to pinpoint a range of rare genetic disorders by analysing pictures of people’s faces. In a paper

On the morning of August 20, 1968, the Czech playwright Vaclav Havel had a serious hangover. He was at his country home in Liberec after a night of boozing it up with his actor friend

On the morning of August 20, 1968, the Czech playwright Vaclav Havel had a serious hangover. He was at his country home in Liberec after a night of boozing it up with his actor friend  My wife and I took a peek into the interior of Papua New Guinea twenty years ago.

My wife and I took a peek into the interior of Papua New Guinea twenty years ago.