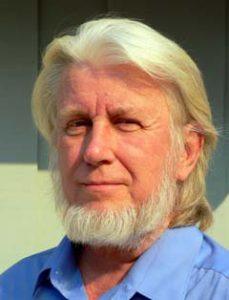

Ronald Aronson in the Boston Review:

Hope is being privatized. Throughout the world, but especially in the United States and the United Kingdom, a seismic shift is underway, displacing aspirations and responsibilities from the larger society to our own individual universes. The detaching of personal expectations from the wider world transforms both.

Hope is being privatized. Throughout the world, but especially in the United States and the United Kingdom, a seismic shift is underway, displacing aspirations and responsibilities from the larger society to our own individual universes. The detaching of personal expectations from the wider world transforms both.

The phenomenon is usually described as “individualization” resulting from broad trends of social evolution, leading as Thomas Edsall described it in the New York Times, to “an inexorable pressure on individuals to, in effect, fly solo.” This suggests that the individualized society is a normal phase of historical development. However, the privatization of hope is a more compelling framework by which to understand this moment. It refers to political, economic, and ideological projects of the past two generations, including the deliberate construction of the consumer economy and then the turn toward neoliberalism. We have not lost all hope over the past generation; there is a maddening profusion of personal hopes. Under attack has been the kind of hope that is social, the motivation behind movements to make the world freer, more equal, more democratic, and more livable.

Not only does this privatization weaken collective capacities to solve collective problems, but it also deadens the very sense that collectivity can or should exist, as the commons dissolves and social sources of problems become hidden.

More here.

Don’t start with a moral theory, start with where you actually are. Here is a question that I think ethicists should be asking alongside Nagel’s famous question about bats (at the moment I want to use it as the title of Epiphanies Chapter 4): “What is it like to be a human being?” So start with that. Start with what it’s like to be you, with your subjectivity here and now, with what looks serious and real and important and beautiful and (yes, why not?) fun to you just as you are, from your own viewpoint. Because actually that’s the only place you ever can start from, really, and one tendency of systematising theories is to obscure this truth.

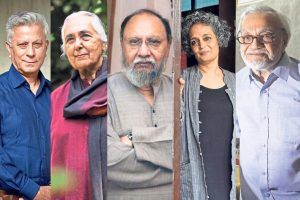

Don’t start with a moral theory, start with where you actually are. Here is a question that I think ethicists should be asking alongside Nagel’s famous question about bats (at the moment I want to use it as the title of Epiphanies Chapter 4): “What is it like to be a human being?” So start with that. Start with what it’s like to be you, with your subjectivity here and now, with what looks serious and real and important and beautiful and (yes, why not?) fun to you just as you are, from your own viewpoint. Because actually that’s the only place you ever can start from, really, and one tendency of systematising theories is to obscure this truth. Talking about the public role of intellectuals in today’s world, and more specifically in India, is of great significance given changes taking place in culture and politics. It is not simply enough to talk about the role of Indian public intellectuals in the making and preserving of critical mindedness and democratic engagement in Indian academia. One should also pay attention to the role which could and should be played by public intellectuals in promoting moral and political excellence and civic friendship among the future generation of Indians.

Talking about the public role of intellectuals in today’s world, and more specifically in India, is of great significance given changes taking place in culture and politics. It is not simply enough to talk about the role of Indian public intellectuals in the making and preserving of critical mindedness and democratic engagement in Indian academia. One should also pay attention to the role which could and should be played by public intellectuals in promoting moral and political excellence and civic friendship among the future generation of Indians. You slide the key into the door and hear a clunk as the tumblers engage. You rotate the key, twist the doorknob and walk inside. The house is familiar, but the contents foreign. At your left, there’s a map of Minnesota, dangling precariously from the wall. You’re certain it wasn’t there this morning. Below it, you find a plush M&M candy. To the right, a dog, a shiba inu you’ve never seen before. In its mouth, a pair of your expensive socks.

You slide the key into the door and hear a clunk as the tumblers engage. You rotate the key, twist the doorknob and walk inside. The house is familiar, but the contents foreign. At your left, there’s a map of Minnesota, dangling precariously from the wall. You’re certain it wasn’t there this morning. Below it, you find a plush M&M candy. To the right, a dog, a shiba inu you’ve never seen before. In its mouth, a pair of your expensive socks. In his new book, The Origins of Dislike, Amit Chaudhuri unwraps several aspects of reading, writing, publishing, criticism, and thinking in general, mostly to dismantle the perceived virtuosity of these phenomena.

In his new book, The Origins of Dislike, Amit Chaudhuri unwraps several aspects of reading, writing, publishing, criticism, and thinking in general, mostly to dismantle the perceived virtuosity of these phenomena. This week, the American Psychological Association, the country’s largest professional organization of psychologists, did something for men that it’s done for many other demographic groups in the past: It introduced

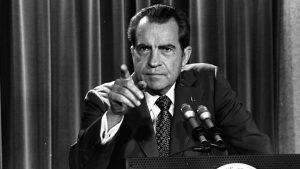

This week, the American Psychological Association, the country’s largest professional organization of psychologists, did something for men that it’s done for many other demographic groups in the past: It introduced  There is, many believe, a specter haunting the Euro-American world. It is not, as Marx and Engels once exulted, the specter of communism. Nor is it the specter of fascism, though some, including former secretary of state Madeleine Albright, have warned of this. Rather, it is the specter of what journalists, scholars, and other political observers now routinely call “populism.” To be sure, there are few, if any, self-described populist movements afoot: no “populist” parties seeking to mobilize voters and constituencies, no “populist international” attempting to harness discontent as it spreads across national borders. Nor is there any “populist” language, sustained “populist” critique of the status quo, or “populist” platform as there once was in the United States at the very end of the 19th century.

There is, many believe, a specter haunting the Euro-American world. It is not, as Marx and Engels once exulted, the specter of communism. Nor is it the specter of fascism, though some, including former secretary of state Madeleine Albright, have warned of this. Rather, it is the specter of what journalists, scholars, and other political observers now routinely call “populism.” To be sure, there are few, if any, self-described populist movements afoot: no “populist” parties seeking to mobilize voters and constituencies, no “populist international” attempting to harness discontent as it spreads across national borders. Nor is there any “populist” language, sustained “populist” critique of the status quo, or “populist” platform as there once was in the United States at the very end of the 19th century. SINCE ITS FOUNDING in the early 20th century, the U.S. Border Patrol has operated with near-complete impunity, arguably serving as the most politicized and abusive branch of federal law enforcement — even more so than the FBI during J. Edgar Hoover’s directorship.

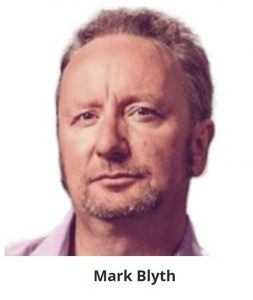

SINCE ITS FOUNDING in the early 20th century, the U.S. Border Patrol has operated with near-complete impunity, arguably serving as the most politicized and abusive branch of federal law enforcement — even more so than the FBI during J. Edgar Hoover’s directorship. Mark Blyth: It’s always a tough one. I hate using the word ‘crisis’, because I’ve been doing this stuff for about 30 years now, and when I went to graduate school I read books about crisis. Then we had a crisis. Then we had another crisis. A crisis of this and a crisis of that. There’s a danger that the term becomes meaningless. So I will try and put it in a slightly different cast.

Mark Blyth: It’s always a tough one. I hate using the word ‘crisis’, because I’ve been doing this stuff for about 30 years now, and when I went to graduate school I read books about crisis. Then we had a crisis. Then we had another crisis. A crisis of this and a crisis of that. There’s a danger that the term becomes meaningless. So I will try and put it in a slightly different cast. David Ellerman works in disparate fields, from economics and political economy, to social theory and philosophy, to mathematical logic and quantum mechanics. From 1992 to 2003, he worked, at the World Bank, as economic advisor to the Chief Economist (Joseph Stiglitz and Nicholas Stern). He has published numerous articles and books, among which The Democratic Worker-Owned Firm (1990), Property and Contract in Economics: The Case for Economic Democracy (1992), and Helping People Help Themselves: From the World Bank to an Alternative Philosophy of Development Assistance (2005). He is currently visiting scholar at the University of California, Riverside and the University of Ljubljana, Slovenia.

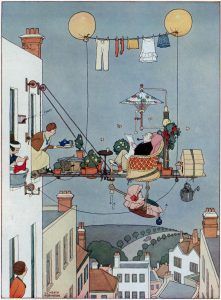

David Ellerman works in disparate fields, from economics and political economy, to social theory and philosophy, to mathematical logic and quantum mechanics. From 1992 to 2003, he worked, at the World Bank, as economic advisor to the Chief Economist (Joseph Stiglitz and Nicholas Stern). He has published numerous articles and books, among which The Democratic Worker-Owned Firm (1990), Property and Contract in Economics: The Case for Economic Democracy (1992), and Helping People Help Themselves: From the World Bank to an Alternative Philosophy of Development Assistance (2005). He is currently visiting scholar at the University of California, Riverside and the University of Ljubljana, Slovenia. It’s one thing for an artist to establish a reputation, another for them to enter the dictionary. When the British want to describe a whimsical, improvised or over-elaborate mechanism, they call it a “Heath Robinson” machine, after the drawings of William Heath Robinson. (Americans have a direct equivalent in Rube Goldberg, whose creations, inspired by similar rapid changes in society and technology, are remarkably similar to those of his British counterpart.) A new exhibition of Heath Robinson’s work shows how he became a household name, in more ways than one.

It’s one thing for an artist to establish a reputation, another for them to enter the dictionary. When the British want to describe a whimsical, improvised or over-elaborate mechanism, they call it a “Heath Robinson” machine, after the drawings of William Heath Robinson. (Americans have a direct equivalent in Rube Goldberg, whose creations, inspired by similar rapid changes in society and technology, are remarkably similar to those of his British counterpart.) A new exhibition of Heath Robinson’s work shows how he became a household name, in more ways than one. A male flame bowerbird is a creature of incandescent beauty. The hue of his plumage transitions seamlessly from molten red to sunshine yellow. But that radiance is not enough to attract a mate. When males of most bowerbird species are ready to begin courting, they set about building the structure for which they are named: an assemblage of twigs shaped into a spire, corridor or hut. They decorate their bowers with scores of colorful objects, like flowers, berries, snail shells or, if they are near an urban area, bottle caps and plastic cutlery. Some bowerbirds even arrange the items in their collection from smallest to largest, forming a walkway that makes themselves and their trinkets all the more striking to a female — an optical illusion known as forced perspective that humans did not perfect until the 15th century. Yet even this remarkable exhibition is not sufficient to satisfy a female flame bowerbird. Should a female show initial interest, the male must react immediately. Staring at the female, his pupils swelling and shrinking like a heartbeat, he begins a dance best described as psychotically sultry. He bobs, flutters, puffs his chest. He crouches low and rises slowly, brandishing one wing in front of his head like a magician’s cape. Suddenly his whole body convulses like a windup alarm clock. If the female approves, she will copulate with him for two or three seconds. They will never meet again.

A male flame bowerbird is a creature of incandescent beauty. The hue of his plumage transitions seamlessly from molten red to sunshine yellow. But that radiance is not enough to attract a mate. When males of most bowerbird species are ready to begin courting, they set about building the structure for which they are named: an assemblage of twigs shaped into a spire, corridor or hut. They decorate their bowers with scores of colorful objects, like flowers, berries, snail shells or, if they are near an urban area, bottle caps and plastic cutlery. Some bowerbirds even arrange the items in their collection from smallest to largest, forming a walkway that makes themselves and their trinkets all the more striking to a female — an optical illusion known as forced perspective that humans did not perfect until the 15th century. Yet even this remarkable exhibition is not sufficient to satisfy a female flame bowerbird. Should a female show initial interest, the male must react immediately. Staring at the female, his pupils swelling and shrinking like a heartbeat, he begins a dance best described as psychotically sultry. He bobs, flutters, puffs his chest. He crouches low and rises slowly, brandishing one wing in front of his head like a magician’s cape. Suddenly his whole body convulses like a windup alarm clock. If the female approves, she will copulate with him for two or three seconds. They will never meet again. Perhaps no author has made more art of dispossession than Ruth Prawer Jhabvala. The author of a dozen novels and twice as many screenplays — she’s the only person to have won both the Booker Prize (for her eighth and best-known novel, “Heat and Dust”) and an Academy Award (twice, for best adapted screenplay) — Jhabvala was 12 when she fled Nazi Germany with her family in 1939. After the war, when her father learned the fate of the relatives left behind, he killed himself.

Perhaps no author has made more art of dispossession than Ruth Prawer Jhabvala. The author of a dozen novels and twice as many screenplays — she’s the only person to have won both the Booker Prize (for her eighth and best-known novel, “Heat and Dust”) and an Academy Award (twice, for best adapted screenplay) — Jhabvala was 12 when she fled Nazi Germany with her family in 1939. After the war, when her father learned the fate of the relatives left behind, he killed himself.

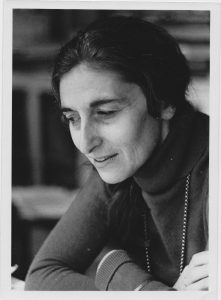

“We are in considerable doubt that you will develop into our professional stereotype of what an experimental psychologist should be.” When the Harvard psychology department kicked Judith Rich Harris out of their PhD program in 1960, they could not have known how true the words in their expulsion letter would turn out to be.

“We are in considerable doubt that you will develop into our professional stereotype of what an experimental psychologist should be.” When the Harvard psychology department kicked Judith Rich Harris out of their PhD program in 1960, they could not have known how true the words in their expulsion letter would turn out to be.

When

When  Having read his book carefully, I believe it’s crucially important to take Pinker to task for some dangerously erroneous arguments he makes. Pinker is, after all, an intellectual darling of the most powerful echelons of global society. He

Having read his book carefully, I believe it’s crucially important to take Pinker to task for some dangerously erroneous arguments he makes. Pinker is, after all, an intellectual darling of the most powerful echelons of global society. He