by Jonathan Kujawa

With the end of daylight savings time, the long, dark nights of winter slump over the land. It is the season for cold nights, warm blankets, and reading good books with a nice cup of tea (or a dram of scotch, if you prefer). Unless, of course, you live in Hawaii or the southern hemisphere, in which case you’ll have to content yourself with reading in a convenient hammock.

Popular math books are a sub-sub-sub-genre of nonfiction, found at a local bookstore in the Nonfiction-Science-Math-“Math? For fun? Really? Ok, if you say so.” section. Even within that narrow span of the bookshelf, you’ll find there are a wide variety of popular math books. Some ambitiously try to give you a sense of deep, modern topics of research like the geometric Langlands program or statistical mechanics. Although I suspect those mainly succeed in giving Hawking’s “A Brief History of Time” and Piketty’s “Capital” a run in the category of many sold but few actually read. Other authors lean towards biography. While interesting and enjoyable reads, they are not often about math, per se. I’m looking forward to someday getting to Siobhan Roberts’ well-reviewed biographies of Coxeter and Conway. Both sound great! But such books necessarily can only hint at the amazing math their subjects have done.

Perhaps unavoidably, too many popular math books end up missing the mark. Trying to talk math without the technicalities, the authors are left leaning on old standbys like the irrationality of √ 2, Hilbert’s Hotel and the marvels of infinity, and picture friendly topics like fractals. It’s a bit like eating a big bowl of oatmeal: a whole lot of familiar filling with the occasional pleasant surprise mixed in. Not that I’m throwing stones! My house here at 3QD is built from its share of tired metaphors, mathematical and otherwise. Every person who writes about math knows the truism: every equation you include cuts your readership in half. But talking about math without, you know, writing down any math is darn hard. It’s like writing about music or poetry in strict essay form. Read more »

This year – 2018 – marks something truly auspicious. This is the semi-centennial of the invention of the Zombie. In these fifty years, let’s face it, we have been completely overrun. Zombies are everywhere. They are in our movies, tv shows, books, and comic books, plus, out here in the real world where the Center for Disease Control has a comprehensive Zombie preparedness and education plan and there are Zombie-walks, Zombie-conventions, and, anyway, didn’t you see them this Halloween? The most popular Zombie tv show, “The Walking Dead”, has been streaming for almost ten years – and the comic book it is based on is still going strong. At least one Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award winning author has written a straight-up zombie novel – Colson Whitehead’s “Zone One”. So, what’s with all the Zombies?

This year – 2018 – marks something truly auspicious. This is the semi-centennial of the invention of the Zombie. In these fifty years, let’s face it, we have been completely overrun. Zombies are everywhere. They are in our movies, tv shows, books, and comic books, plus, out here in the real world where the Center for Disease Control has a comprehensive Zombie preparedness and education plan and there are Zombie-walks, Zombie-conventions, and, anyway, didn’t you see them this Halloween? The most popular Zombie tv show, “The Walking Dead”, has been streaming for almost ten years – and the comic book it is based on is still going strong. At least one Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award winning author has written a straight-up zombie novel – Colson Whitehead’s “Zone One”. So, what’s with all the Zombies?

“They all go the same way. Look up, then down and to the left,” the EMT said. “Always.”

“They all go the same way. Look up, then down and to the left,” the EMT said. “Always.”

In Tian Shan mountains of the legendary snow leopard, errant wisps of mist float with the speed of scurrying ghosts, there is a climbers’ cemetery, Himalayan Griffin vultures and golden eagles are often sighted, though my attention is completely arrested by a Blue whistling thrush alighting on a rock— its plumage, its slender, seemingly weightless frame, and its long drawn, ventriloquist song remind me of the fairies of Alif Laila that were turned to birds by demons inhabiting barren mountains.

In Tian Shan mountains of the legendary snow leopard, errant wisps of mist float with the speed of scurrying ghosts, there is a climbers’ cemetery, Himalayan Griffin vultures and golden eagles are often sighted, though my attention is completely arrested by a Blue whistling thrush alighting on a rock— its plumage, its slender, seemingly weightless frame, and its long drawn, ventriloquist song remind me of the fairies of Alif Laila that were turned to birds by demons inhabiting barren mountains.

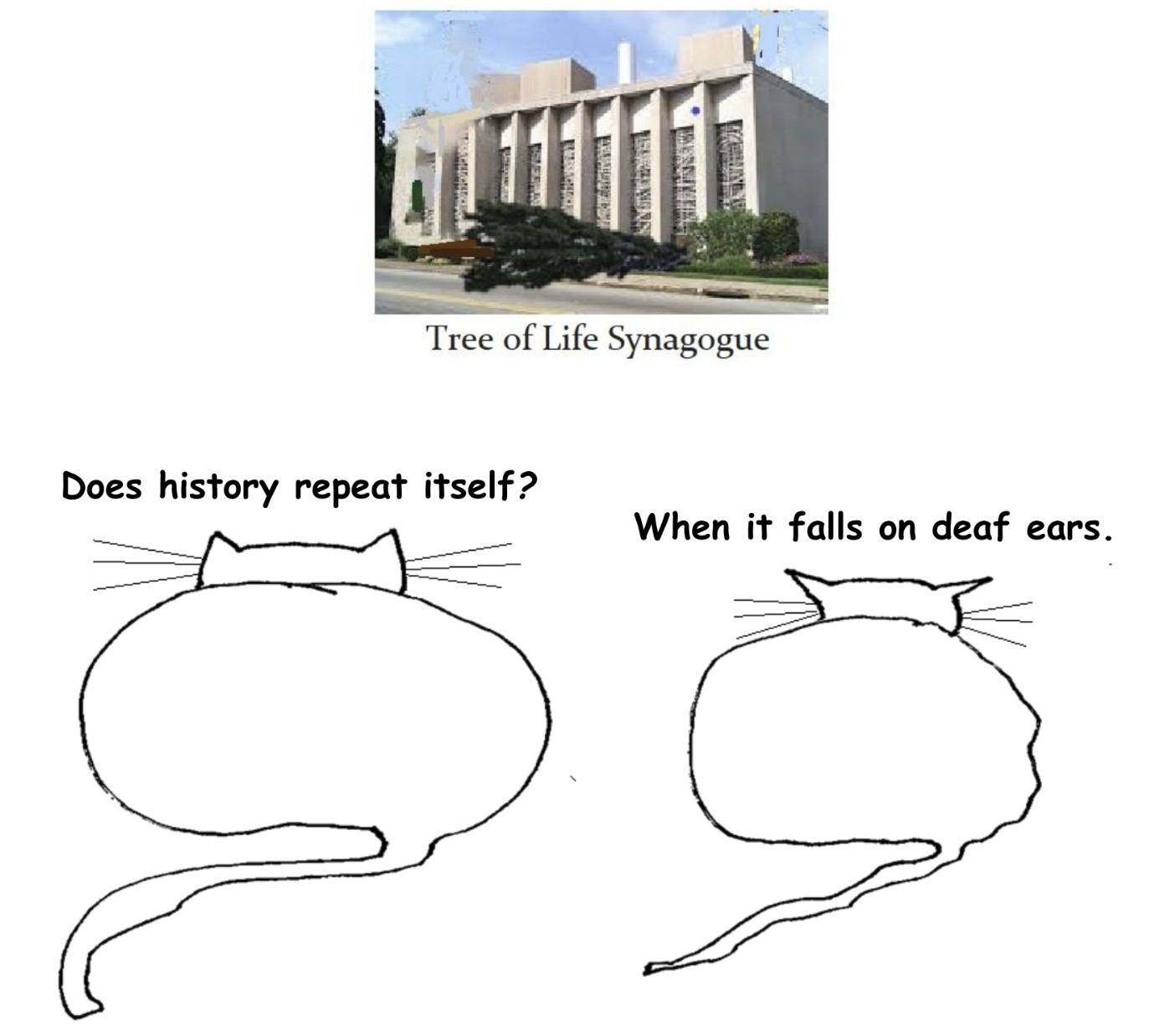

On a recent windy morning, walking past the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument on West 89th Street in New York City, seeing the flag at half mast, just days before the

On a recent windy morning, walking past the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument on West 89th Street in New York City, seeing the flag at half mast, just days before the  April 2018: ‘Tis the Season of Giddiness in Democratlandia. Republicans are saddled with a widely despised President and riven by internal dissension. The Republican leadership in Congress is lurching from fiasco to fiasco – interrupted briefly by one great “success” on tax cuts. The zombie candidates of the Tea Party are still stalking establishment Republicans across the land. And, somewhere in his formidable fastness, the Great Dragon Mueller is winding up for the fiery breath that will consume the world of Trumpism like a paper lantern. And a Blue Wave – nay, a Tsunami – is headed towards the Republicans in Congress, looking to engulf them in November.

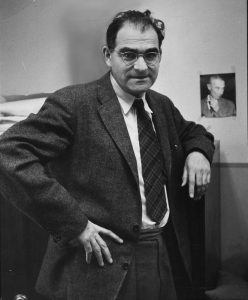

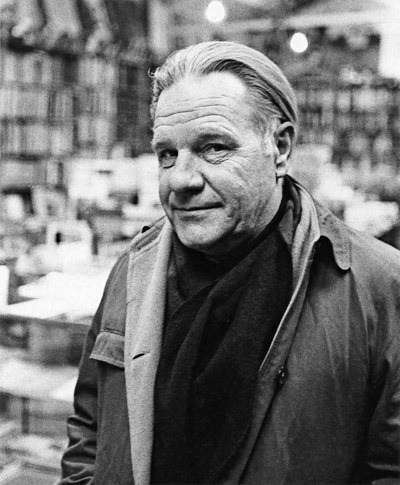

April 2018: ‘Tis the Season of Giddiness in Democratlandia. Republicans are saddled with a widely despised President and riven by internal dissension. The Republican leadership in Congress is lurching from fiasco to fiasco – interrupted briefly by one great “success” on tax cuts. The zombie candidates of the Tea Party are still stalking establishment Republicans across the land. And, somewhere in his formidable fastness, the Great Dragon Mueller is winding up for the fiery breath that will consume the world of Trumpism like a paper lantern. And a Blue Wave – nay, a Tsunami – is headed towards the Republicans in Congress, looking to engulf them in November. Victor Weisskopf (Viki to his friends) emigrated to the United States in the 1930s as part of the windfall of Jewish European emigre physicists which the country inherited thanks to Adolf Hitler. In many ways Weisskopf’s story was typical of his generation’s: born to well-to-do parents in Vienna at the turn of the century, educated in the best centers of theoretical physics – Göttingen, Zurich and Copenhagen – where he learnt quantum mechanics from masters like Wolfgang Pauli, Werner Heisenberg and Niels Bohr, and finally escaping the growing tentacles of fascism to make a home for himself in the United States where he flourished, first at Rochester and then at MIT. He worked at Los Alamos on the bomb, then campaigned against it as well as against the growing tide of red-baiting in the United States. A beloved teacher and researcher, he was also the first director-general of CERN, a laboratory which continues to work at the forefront of particle physics and rack up honors.

Victor Weisskopf (Viki to his friends) emigrated to the United States in the 1930s as part of the windfall of Jewish European emigre physicists which the country inherited thanks to Adolf Hitler. In many ways Weisskopf’s story was typical of his generation’s: born to well-to-do parents in Vienna at the turn of the century, educated in the best centers of theoretical physics – Göttingen, Zurich and Copenhagen – where he learnt quantum mechanics from masters like Wolfgang Pauli, Werner Heisenberg and Niels Bohr, and finally escaping the growing tentacles of fascism to make a home for himself in the United States where he flourished, first at Rochester and then at MIT. He worked at Los Alamos on the bomb, then campaigned against it as well as against the growing tide of red-baiting in the United States. A beloved teacher and researcher, he was also the first director-general of CERN, a laboratory which continues to work at the forefront of particle physics and rack up honors.

When you consume a meal, do you eat cow or beef? Yes, these are the same, especially considering where they end up, but we tend to think of the cow as the beginning of this particular process, and the beef as the product. More of these pairings include calf/veal, swine or pig/pork, sheep/mutton, hen or chicken/poultry, deer/venison, snail/escargot.

When you consume a meal, do you eat cow or beef? Yes, these are the same, especially considering where they end up, but we tend to think of the cow as the beginning of this particular process, and the beef as the product. More of these pairings include calf/veal, swine or pig/pork, sheep/mutton, hen or chicken/poultry, deer/venison, snail/escargot.

It could almost be a question on a very meta personality quiz: Do you prefer the Myers-Briggs typology or the Big Five personality traits? The Myers-Brigg Type Inventory is a popular tool that was developed outside of the scientific establishment by two women who did not have credentials in psychology. It’s qualitative rather than quantitative, and in the past decade or so, it’s been criticized as meaningless or unscientific. The Big Five taxonomy is widely accepted in academia and is the basis of much current personality research. It’s quantitative; in fact, it’s based on statistical analysis. Am I rejecting science if I continue to prefer the Myers-Briggs system as a key to understanding my own personality and those of others?

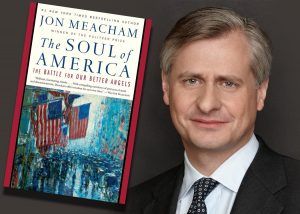

It could almost be a question on a very meta personality quiz: Do you prefer the Myers-Briggs typology or the Big Five personality traits? The Myers-Brigg Type Inventory is a popular tool that was developed outside of the scientific establishment by two women who did not have credentials in psychology. It’s qualitative rather than quantitative, and in the past decade or so, it’s been criticized as meaningless or unscientific. The Big Five taxonomy is widely accepted in academia and is the basis of much current personality research. It’s quantitative; in fact, it’s based on statistical analysis. Am I rejecting science if I continue to prefer the Myers-Briggs system as a key to understanding my own personality and those of others? It is difficult to remember a time over recent decades when a president of the United States (US) has created so much controversy and division within the US and challenged its credibility and standing in international relations as has the incumbent president, Donald Trump. Indeed, so bewildering to many is the election of a former reality TV star and dubious businessman without experience in government, to the high office of president of the US and ‘leader’ of the ‘free’ world, a plethora of literature to account for such a phenomenon has emerged. Similarly, commentaries on evaluations of Trump’s calibre and character, and just how far he is fit for such high office and powerful position in global politics, are plentiful. Jon Meacham’s The Soul of America: The Battle for Our Better Angels can be viewed as a contribution to the literature on those issues.

It is difficult to remember a time over recent decades when a president of the United States (US) has created so much controversy and division within the US and challenged its credibility and standing in international relations as has the incumbent president, Donald Trump. Indeed, so bewildering to many is the election of a former reality TV star and dubious businessman without experience in government, to the high office of president of the US and ‘leader’ of the ‘free’ world, a plethora of literature to account for such a phenomenon has emerged. Similarly, commentaries on evaluations of Trump’s calibre and character, and just how far he is fit for such high office and powerful position in global politics, are plentiful. Jon Meacham’s The Soul of America: The Battle for Our Better Angels can be viewed as a contribution to the literature on those issues.