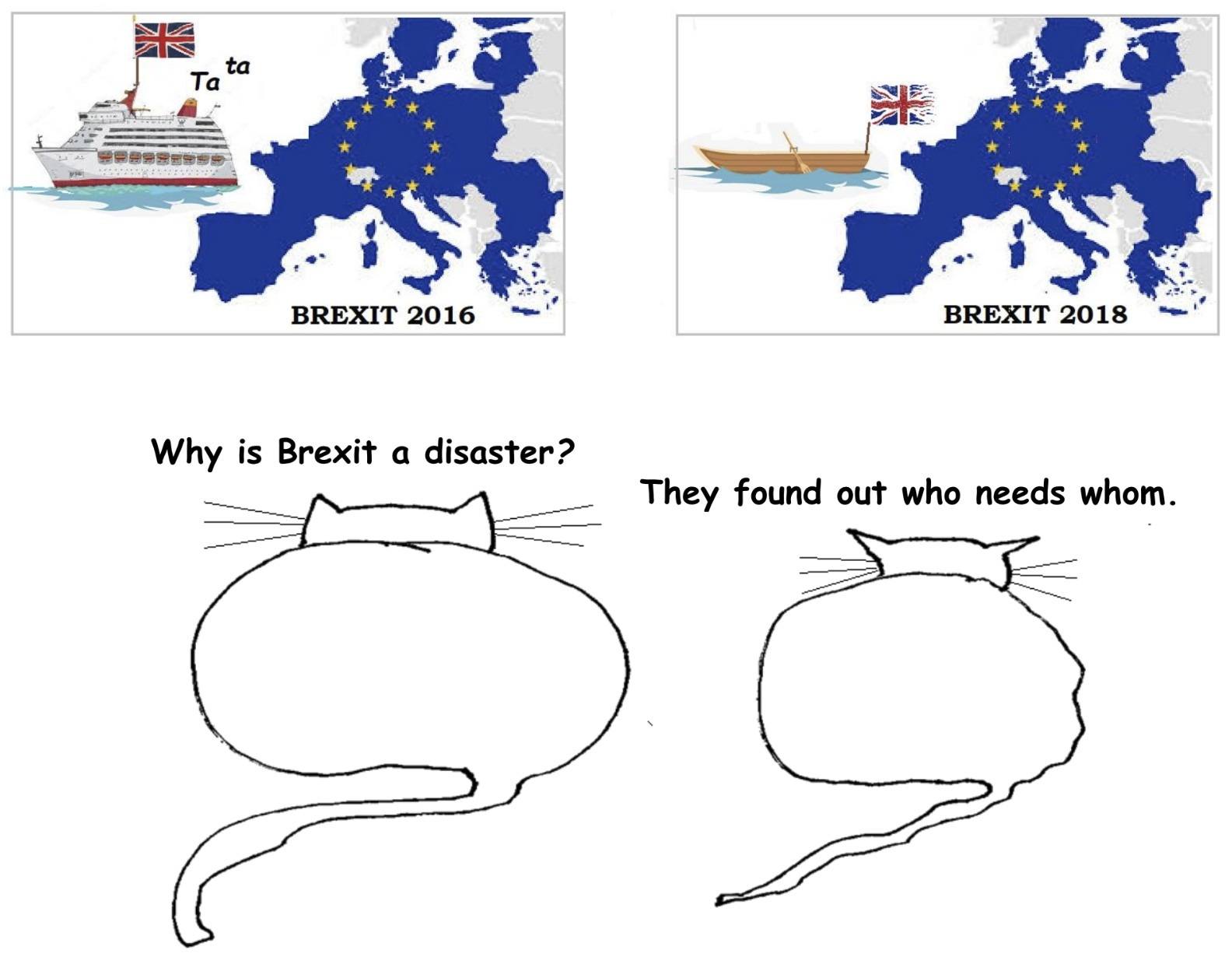

by Michael Liss

The day before Thanksgiving I got this wonderfully understated text from a close friend:

The day before Thanksgiving I got this wonderfully understated text from a close friend:

A ???? ate our ???? last night. (I forgot it on the patio while it was brining.)

There is a lot that’s packed in there. He followed it up with a picture of the now-overturned and empty brining vessel, and a quite stunning shot of bear tracks in the snow leading away from the patio. Unless a local who knew of his remarkable culinary skill with fowl decided to approach the house wearing bear-claw flip-flops (to throw him off the scent, as it were), there was definitely a visitation from a neighborhood ursus americanus.

Fortunately, he resides in a rather bucolic part of a rather bucolic college town, which enables him and his family to live a bucolic life…, but they have access to several Whole Foods, Trader Joe’s and similar establishments when these unexpected encounters occur. The turkey in question was, in absentia, bid a respectful adieu, and quickly and calmly replaced. My friend happens to be unflappable. I, on the other hand, am more urban, and have more flap about these kind of things, so I asked a follow-up question. As the brined bird and the bear claw were really close to the back door, was he prepared to exercise his 2nd Amendment rights, if hearth and home were threatened. I’ll leave the answer to that one to the imagination.

Wild game and guns, a perfect lead-in to the Midterms and the Whole Foods-Cracker Barrel Old Country Store split that pollsters identified. Cracker Barrel has exactly one location in each of Maine, Rhode Island, and New Hampshire, two in Connecticut, eight in Massachusetts (take that, Michael Dukakis), and none in Vermont. By contrast, it has 39 in West Virginia, with nary a Whole Foods in sight. In January (numbers from Dave Wasserman, the U.S. House Editor of the non-partisan Cook Political Report), House Democrats will represent 78% of Whole Foods communities and 27% of Cracker Barrel ones. Apparently, my people are better with organic duck breast pate than chicken-fried steak.

OK, I’ve had my fun, so let’s get down to the actual meal. There were a couple of bumps (like the Senate), but, on the whole, the Democrats did quite well in November—at current count, they flipped a net 40 Congressional Districts, 400+ State legislators, 7 Governors, and an assorted contingent of State Treasurers, Secretaries of State, Commissioners and other sub-luminaries. Read more »

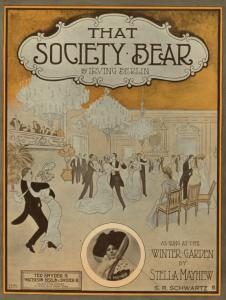

Certain phrases choke us with their ubiquity at some point:

Certain phrases choke us with their ubiquity at some point:

As we approach the end of the year, it’s that time again. Not to flip the page to the next month, but to buy a new calendar. (Who am I kidding? It’s probably only me and your grandmother who still uses paper wall calendars…) And also to reflect.

As we approach the end of the year, it’s that time again. Not to flip the page to the next month, but to buy a new calendar. (Who am I kidding? It’s probably only me and your grandmother who still uses paper wall calendars…) And also to reflect.  Guinea and Redhead were part of a large food chain. Beyond campus’ freshly-baked sidewalks, a Cowboy Mafia ferried contraband from the south. They landed small prop planes on ranch land outside of town, cut powder with dental anesthetics and broke up the bales. Their wares clumped on our cafeteria trays and glinted in tiny screw-top bottles. The capo, a local big-hat business man,who ran a palatial kicker-dance hall and owned the ranch. That legit business and his crew’s discipline kept them out of jail. Maybe a hat full of cash in the bargain.

Guinea and Redhead were part of a large food chain. Beyond campus’ freshly-baked sidewalks, a Cowboy Mafia ferried contraband from the south. They landed small prop planes on ranch land outside of town, cut powder with dental anesthetics and broke up the bales. Their wares clumped on our cafeteria trays and glinted in tiny screw-top bottles. The capo, a local big-hat business man,who ran a palatial kicker-dance hall and owned the ranch. That legit business and his crew’s discipline kept them out of jail. Maybe a hat full of cash in the bargain. Philosophers are supposed to ask Big Questions. The Big Questions is the title of a popular introduction to philosophy and of a long-running BBC programme in which people discuss their ethical and religious perspectives. But since we philosophers, following in the footsteps of Socrates, claim to practice critical thinking, it behooves us to ask whether Big Questions are a good idea.

Philosophers are supposed to ask Big Questions. The Big Questions is the title of a popular introduction to philosophy and of a long-running BBC programme in which people discuss their ethical and religious perspectives. But since we philosophers, following in the footsteps of Socrates, claim to practice critical thinking, it behooves us to ask whether Big Questions are a good idea. In his Critique of Pure Reason (1781) Kant claimed that in denying knowledge he was “making room for faith.” Inevitably, though, faith in God, the soul and the afterlife has declined dramatically since Kant’s time, especially among intellectuals. There are virtually no articles published in philosophy journals today that treat the existence of God or the immortality of the soul as live issues. Science does not explicitly teach us that there is no God and no heaven, any more than it teaches us that there are no fairies or vampires. But the default attitude of most professional philosophers today is that in such matters the absence of evidence amounts to evidence of absence.

In his Critique of Pure Reason (1781) Kant claimed that in denying knowledge he was “making room for faith.” Inevitably, though, faith in God, the soul and the afterlife has declined dramatically since Kant’s time, especially among intellectuals. There are virtually no articles published in philosophy journals today that treat the existence of God or the immortality of the soul as live issues. Science does not explicitly teach us that there is no God and no heaven, any more than it teaches us that there are no fairies or vampires. But the default attitude of most professional philosophers today is that in such matters the absence of evidence amounts to evidence of absence.

Mandra health center, outside Islamabad, on this spring morning, without the cacophony and confusion of health centers in the city, was the picture of serenity. An emaciated woman of indeterminate age sits coughing in the corridor, in a chair that bears the logo of the United States Agency for International Development, next to a little girl with dry shoulder length hair and yellow eyes, one bare foot resting upon the other. I make a provisional diagnosis—pulmonary tuberculosis for the woman, viral hepatitis for the girl, both diseases endemic in Pakistan.

Mandra health center, outside Islamabad, on this spring morning, without the cacophony and confusion of health centers in the city, was the picture of serenity. An emaciated woman of indeterminate age sits coughing in the corridor, in a chair that bears the logo of the United States Agency for International Development, next to a little girl with dry shoulder length hair and yellow eyes, one bare foot resting upon the other. I make a provisional diagnosis—pulmonary tuberculosis for the woman, viral hepatitis for the girl, both diseases endemic in Pakistan.

From its origins in Eurasia some 8,000 years ago, wine has spread to become a staple at dinner tables throughout the world. Yet wine is more than just a beverage. People devote a lifetime to its study, spend fortunes tracking down rare bottles, and give up respectable, lucrative careers to spend their days on a tractor or hosing out barrels, while incurring the risk of making a product utterly dependent on the uncertainties of nature. For them, wine is an object of love.

From its origins in Eurasia some 8,000 years ago, wine has spread to become a staple at dinner tables throughout the world. Yet wine is more than just a beverage. People devote a lifetime to its study, spend fortunes tracking down rare bottles, and give up respectable, lucrative careers to spend their days on a tractor or hosing out barrels, while incurring the risk of making a product utterly dependent on the uncertainties of nature. For them, wine is an object of love. Academics have a privileged epistemic position in society. They deserve to be listened to, their claims believed, and their recommendations considered seriously. What they say about their subject of expertise is more likely to be true than what anyone else has to say about it.

Academics have a privileged epistemic position in society. They deserve to be listened to, their claims believed, and their recommendations considered seriously. What they say about their subject of expertise is more likely to be true than what anyone else has to say about it. The day before Thanksgiving I got this wonderfully understated text from a close friend:

The day before Thanksgiving I got this wonderfully understated text from a close friend: