by Thomas O’Dwyer

A pretty doll in a box at the foot of the bed – what could make a better Christmas morning for a little girl?

“Aaw, she’s so pretty.” The doll promised happy days to come – hair to brush and style, outfits to make and match, private chats to be had. Good chats, with someone who only listened, never talked. A doll was the essence of childhood for millions of young girls over centuries, even millennia. A toy became a baby, a little sister or even a “little me”. The doll was a simple thing until the middle of the last century but alas, it is no longer, like childhood itself.

“You can’t find toys like that anymore,” say the oldsters about their memories of playthings. In reality, grumbling adults are indifferent to such things, unless they are collectors. To children, toys and dolls are as new and exciting as they have ever been. We may think modern dolls have morphed into figures of complexity, controversy and even creepiness. They have become trend setters, celebrities and psychotic misfits – analysed, criticised, rarely praised. Are dolls still loved? Are they innocent companions – or sexist props, propagandists for adulthood, training aids for womanhood?

It is narcissistic, this human urge to fashion models of ourselves, and it’s quite ancient. In prehistory, dolls represented some aspect of religion. Gods themselves are invisible dolls, fashioned in the human image and likeness. Early dolls were fetishes. The origin of this word was in sorcery, charms and spells, exposing the purpose of dolls. The fetish differs from an idol in that it is worshipped for itself, not as a representative of an invisible spirit. Read more »

As we approach the end of the year, it’s that time again. Not to flip the page to the next month, but to buy a new calendar. (Who am I kidding? It’s probably only me and your grandmother who still uses paper wall calendars…) And also to reflect.

As we approach the end of the year, it’s that time again. Not to flip the page to the next month, but to buy a new calendar. (Who am I kidding? It’s probably only me and your grandmother who still uses paper wall calendars…) And also to reflect.  Guinea and Redhead were part of a large food chain. Beyond campus’ freshly-baked sidewalks, a Cowboy Mafia ferried contraband from the south. They landed small prop planes on ranch land outside of town, cut powder with dental anesthetics and broke up the bales. Their wares clumped on our cafeteria trays and glinted in tiny screw-top bottles. The capo, a local big-hat business man,who ran a palatial kicker-dance hall and owned the ranch. That legit business and his crew’s discipline kept them out of jail. Maybe a hat full of cash in the bargain.

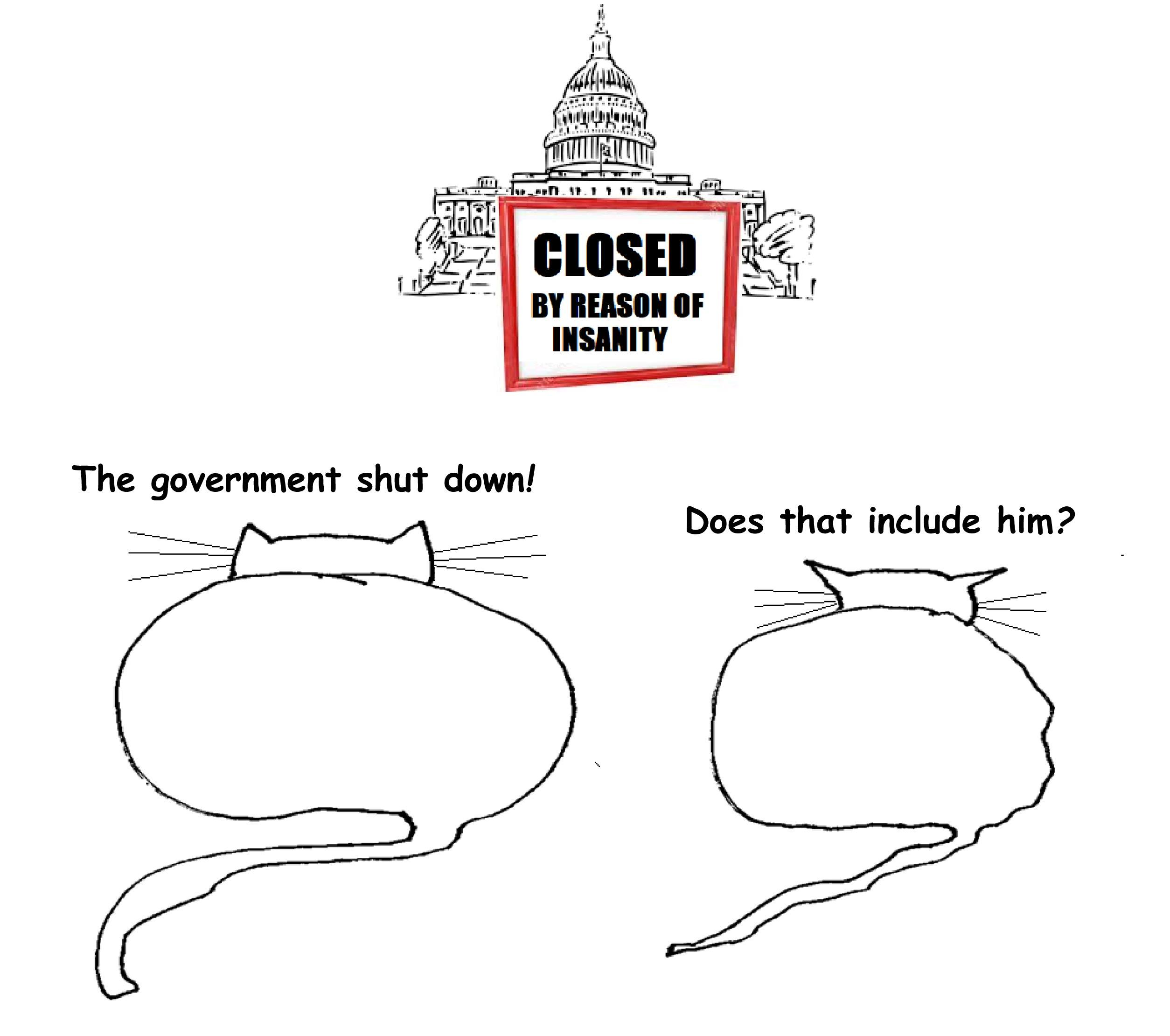

Guinea and Redhead were part of a large food chain. Beyond campus’ freshly-baked sidewalks, a Cowboy Mafia ferried contraband from the south. They landed small prop planes on ranch land outside of town, cut powder with dental anesthetics and broke up the bales. Their wares clumped on our cafeteria trays and glinted in tiny screw-top bottles. The capo, a local big-hat business man,who ran a palatial kicker-dance hall and owned the ranch. That legit business and his crew’s discipline kept them out of jail. Maybe a hat full of cash in the bargain. Philosophers are supposed to ask Big Questions. The Big Questions is the title of a popular introduction to philosophy and of a long-running BBC programme in which people discuss their ethical and religious perspectives. But since we philosophers, following in the footsteps of Socrates, claim to practice critical thinking, it behooves us to ask whether Big Questions are a good idea.

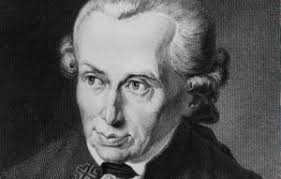

Philosophers are supposed to ask Big Questions. The Big Questions is the title of a popular introduction to philosophy and of a long-running BBC programme in which people discuss their ethical and religious perspectives. But since we philosophers, following in the footsteps of Socrates, claim to practice critical thinking, it behooves us to ask whether Big Questions are a good idea. In his Critique of Pure Reason (1781) Kant claimed that in denying knowledge he was “making room for faith.” Inevitably, though, faith in God, the soul and the afterlife has declined dramatically since Kant’s time, especially among intellectuals. There are virtually no articles published in philosophy journals today that treat the existence of God or the immortality of the soul as live issues. Science does not explicitly teach us that there is no God and no heaven, any more than it teaches us that there are no fairies or vampires. But the default attitude of most professional philosophers today is that in such matters the absence of evidence amounts to evidence of absence.

In his Critique of Pure Reason (1781) Kant claimed that in denying knowledge he was “making room for faith.” Inevitably, though, faith in God, the soul and the afterlife has declined dramatically since Kant’s time, especially among intellectuals. There are virtually no articles published in philosophy journals today that treat the existence of God or the immortality of the soul as live issues. Science does not explicitly teach us that there is no God and no heaven, any more than it teaches us that there are no fairies or vampires. But the default attitude of most professional philosophers today is that in such matters the absence of evidence amounts to evidence of absence.

Mandra health center, outside Islamabad, on this spring morning, without the cacophony and confusion of health centers in the city, was the picture of serenity. An emaciated woman of indeterminate age sits coughing in the corridor, in a chair that bears the logo of the United States Agency for International Development, next to a little girl with dry shoulder length hair and yellow eyes, one bare foot resting upon the other. I make a provisional diagnosis—pulmonary tuberculosis for the woman, viral hepatitis for the girl, both diseases endemic in Pakistan.

Mandra health center, outside Islamabad, on this spring morning, without the cacophony and confusion of health centers in the city, was the picture of serenity. An emaciated woman of indeterminate age sits coughing in the corridor, in a chair that bears the logo of the United States Agency for International Development, next to a little girl with dry shoulder length hair and yellow eyes, one bare foot resting upon the other. I make a provisional diagnosis—pulmonary tuberculosis for the woman, viral hepatitis for the girl, both diseases endemic in Pakistan.

From its origins in Eurasia some 8,000 years ago, wine has spread to become a staple at dinner tables throughout the world. Yet wine is more than just a beverage. People devote a lifetime to its study, spend fortunes tracking down rare bottles, and give up respectable, lucrative careers to spend their days on a tractor or hosing out barrels, while incurring the risk of making a product utterly dependent on the uncertainties of nature. For them, wine is an object of love.

From its origins in Eurasia some 8,000 years ago, wine has spread to become a staple at dinner tables throughout the world. Yet wine is more than just a beverage. People devote a lifetime to its study, spend fortunes tracking down rare bottles, and give up respectable, lucrative careers to spend their days on a tractor or hosing out barrels, while incurring the risk of making a product utterly dependent on the uncertainties of nature. For them, wine is an object of love. Academics have a privileged epistemic position in society. They deserve to be listened to, their claims believed, and their recommendations considered seriously. What they say about their subject of expertise is more likely to be true than what anyone else has to say about it.

Academics have a privileged epistemic position in society. They deserve to be listened to, their claims believed, and their recommendations considered seriously. What they say about their subject of expertise is more likely to be true than what anyone else has to say about it. The day before Thanksgiving I got this wonderfully understated text from a close friend:

The day before Thanksgiving I got this wonderfully understated text from a close friend: