by Thomas Manuel

“The last time there was a protest in this country, they didn’t just arrest everyone – they killed the protestors and carried on killing for weeks after. Ever since then, people here have been very afraid.” “When was this?” I asked. “Nineteen seventy-seven,” he said, “and they killed thousands.” – Lara Pawson, The 27 May in Angola: a view from below

It’s simultaneously sotto voce and hyper-visible. – Marissa Moorman, The battle over the 27th of May in Angola

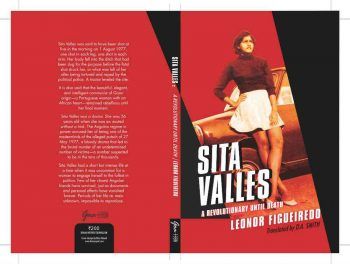

“Sita Maria Dias Valles …remains, for all intents and purposes, missing. Her body was never returned to her family. She was about to turn 26 when she was executed.” – Leonor Figueiredo, Sita Valles: A Revolutionary Until Death

If stories have shapes, this one lies over the sphere of the Earth like a triangle. The three vertices or points of this triangle lie on three different continents: one in India, one in Angola and one in Portugal. But the lines that join these points, that form these vertices, traverse not just space but time.

Goa, India

In the 16th century, Afonso de Albquerque attacks Goa and captures it from the Muslim king who ruled it. Goa becomes the capital of the Portuguese maritime operations in Asia. Through this tiny land, the riches and rarities of South East Asia traveled to Europe. It remained like this for four and a half centuries.

In 1947, the country of India gained its independence and threw off the grasping hands of the British Empire but the Portuguese held on to Goa with a deathly grip. The Salazar regime did not hesitate to shoot and kill Goans who agitated for independence.

In 1961, the Indian army marched into Goa and claimed the land. (In the process, they destroyed a Portuguese frigate named after Afonso de Albquerque. That is the nature of history.) The US and the UK would try to condemn the invasion in the United Nations but the then USSR would veto it. Read more »

In this world of divisive and indeed, not infrequently, ugly politics, particularly in the United States under the present administration, and the British pursuit of an exit from the European Union, any opportunity for finding relief from the ‘angst’ of day to day politics is to be welcomed. The reading of Peter Wohlleben’s The Mysteries of Nature Trilogy: The Hidden Life of Trees, The Secret Network of Nature and The Inner Life of Animals provided me with such an opportunity.

In this world of divisive and indeed, not infrequently, ugly politics, particularly in the United States under the present administration, and the British pursuit of an exit from the European Union, any opportunity for finding relief from the ‘angst’ of day to day politics is to be welcomed. The reading of Peter Wohlleben’s The Mysteries of Nature Trilogy: The Hidden Life of Trees, The Secret Network of Nature and The Inner Life of Animals provided me with such an opportunity.

In the next couple of months two of the largest democracies in the world—India and Indonesia—will have their national elections. At a time when democracy is under considerable pressure everywhere, the electoral and general democratic outcome in these two countries containing in total more than one and a half billion people (more than one and a half times the population in democratic West plus Japan and Australia) will be closely observed.

In the next couple of months two of the largest democracies in the world—India and Indonesia—will have their national elections. At a time when democracy is under considerable pressure everywhere, the electoral and general democratic outcome in these two countries containing in total more than one and a half billion people (more than one and a half times the population in democratic West plus Japan and Australia) will be closely observed.

There is a sense in certain quarters that both experimental and theoretical fundamental physics are at an impasse. Other branches of physics like condensed matter physics and fluid dynamics are thriving, but since the composition and existence of the fundamental basis of matter, the origins of the universe and the unity of quantum mechanics with general relativity have long since been held to be foundational matters in physics, this lack of progress rightly bothers its practitioners.

There is a sense in certain quarters that both experimental and theoretical fundamental physics are at an impasse. Other branches of physics like condensed matter physics and fluid dynamics are thriving, but since the composition and existence of the fundamental basis of matter, the origins of the universe and the unity of quantum mechanics with general relativity have long since been held to be foundational matters in physics, this lack of progress rightly bothers its practitioners.

I was struck by a sentence in Susan Orlean’s The Library Book: “If nothing lasts, nothing matters.” This line was part of a discussion of memory, the fear of being forgotten, and the value of passing things on to future generations. I share a passion for the idea of continuity between generations (and I highly recommend Orlean’s book), but ultimately I don’t think that something has to last to matter. Alan Watts, in his book This Is It, says that “This—the immediate, everyday, and present experience—is IT, the entire and ultimate point for the existence of a universe.” It’s not about connecting with anything but what’s here in front of me now. (Easier said than done, of course.)

I was struck by a sentence in Susan Orlean’s The Library Book: “If nothing lasts, nothing matters.” This line was part of a discussion of memory, the fear of being forgotten, and the value of passing things on to future generations. I share a passion for the idea of continuity between generations (and I highly recommend Orlean’s book), but ultimately I don’t think that something has to last to matter. Alan Watts, in his book This Is It, says that “This—the immediate, everyday, and present experience—is IT, the entire and ultimate point for the existence of a universe.” It’s not about connecting with anything but what’s here in front of me now. (Easier said than done, of course.) I teach two kinds of group exercise classes, and part of the certification processes for both disciplines devoted no small amount of attention to how to speak to your minions, uh, students.

I teach two kinds of group exercise classes, and part of the certification processes for both disciplines devoted no small amount of attention to how to speak to your minions, uh, students. “…And now to introduce our second panelist: Martha. Martha does believe that academic philosophy is worth pursuing, and she has – of course – written a book about it. Martha, can you briefly summarize your argument?”

“…And now to introduce our second panelist: Martha. Martha does believe that academic philosophy is worth pursuing, and she has – of course – written a book about it. Martha, can you briefly summarize your argument?”

My answering machine whirrs. From an echoing room, the chainsaw-voice shouts into a speaker phone:

My answering machine whirrs. From an echoing room, the chainsaw-voice shouts into a speaker phone: One of the philosophical tools that seems utterly obvious to me is the so-called “use/mention distinction”. Because it strikes me as so obvious, it is always baffling to me that people seem to have such trouble with it.

One of the philosophical tools that seems utterly obvious to me is the so-called “use/mention distinction”. Because it strikes me as so obvious, it is always baffling to me that people seem to have such trouble with it.