by Thomas O’Dwyer

Drumcliffe churchyard lies in the shadow of a flat-topped mountain, in the western Irish countryside of Sligo county, on the Atlantic coast. There are remains of a round tower and a carved Celtic high cross. It would be the perfect resting place for a country’s greatest poet – especially if the poet himself had chosen it.

Drumcliffe churchyard lies in the shadow of a flat-topped mountain, in the western Irish countryside of Sligo county, on the Atlantic coast. There are remains of a round tower and a carved Celtic high cross. It would be the perfect resting place for a country’s greatest poet – especially if the poet himself had chosen it.

“Bury me up there on the mountain, Roquebrune,” W.B. Yeats wrote to his wife Georgie before his death in France in 1939. “And then, after a year or so, after the newspapers have forgotten, plant me in Sligo.” The poet died in the Hôtel Idéal Séjour in the nearby town of Menton. His funeral cortege did indeed wind up a narrow hill to where Roquebrune cemetery looks out over the Mediterranean. But then came World War II, and the repatriation of the remains of one Irish poet was unlikely to be a priority for the Nazi-occupied French, or anybody else.

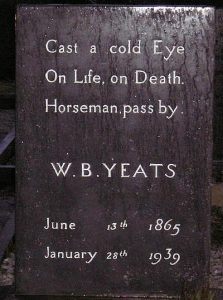

Seventy years ago this autumn, this last wish of Ireland’s first Nobel Prize winner was finally fulfilled. His family and proud countrymen brought him home for a splendid state funeral in his beloved Sligo. Yeats had written of his desired resting place before his death in one of his last poems, Under Ben Bulben. “Under bare Ben Bulben’s head / In Drumcliffe churchyard Yeats is laid, / An ancestor was rector there / Long years ago; a church stands near, / By the road an ancient Cross.” For good measure, he added an epitaph, the same one carved on his tombstone. In 1948, on a typical Irish September day, half sunshine and half rain, W.B. Yeats was laid in his chosen place to rest in peace forever.

Or was he?

Even then, there were whispers that the devious French had tricked the Irish and sent them a box of random bones unconnected to the national poet. Whoever lay in Drumcliffe churchyard, they said, it was not William Butler Yeats. The box of bones became a can of worms nobody wanted to open and the rumours faded. Irish schoolchildren recited Under Ben Bulban, and Sligo happily pinned itself to the world map of literary tourism.

The tales of any Irish hero were moulded into a mythology that fitted the cultural image of what was a new state, but an ancient Celtic nation. The returned W.B. completed a mythic circle and he joined the pantheon headed by his hero Chúculainn, Ireland’s Hercules. “Have not old writers said that dizzy dreams can spring from the dry bones of the dead?” a character says in his play, The Dreaming of the Bones. The romantic and mystical Nobel laureate was the perfect literary myth. His image was an icon — handsome, aristocratic and serious, one that could become a Halloween costume. George Moore, a literary rival of the young poet, wrote a description of him. “Yeats was striding to and fro at the back of the dress circle, a long black cloak drooping from his shoulders, a soft black sombrero on his head, voluminous black silk tie flowing from his collar, loose black trousers dragging untidily over his long, heavy feet. His hair was black and his skin white.”

His life, of course, was that of a poet. There was youthful struggle and depression and hopeless love for an unattainable muse, Maud Gonne, who inspired him. Then came slow recognition of his genius, co-founding of the national Abbey Theatre, marriage to a good woman, the Nobel Prize, and respectability as a Senator of Ireland. National myths do not invite scrutiny and heroes do not do fare well under a microscope. Tour guides, school teachers and state cultural centres like to keep the narrative simple and noble. But, there are also pesky academics, historians, journalists, and busybodies who insist on picking at the scabs of legends with their pens. “What about the real Yeats?” they ask, with annoying persistence. “What about the arrogant snob, the fascist sympathiser, the lifelong womaniser, the dabbler in the idiotic arts – seances, Theosophy, automatic writing? And didn’t Maud Gonne call him ‘Silly Willy’?” And by the way, exactly what is buried under bare Ben Bulben’s head – a bare-faced lie, perhaps?

Eoin “the Pope” O’Mahony was a well known Irish lawyer, broadcaster and raconteur who attended the Yeats funeral in Sligo. In an interview before his death in 1970, he recalled the rumours that were circulating. Asked if he thought the French had deceived the Irish and sent someone else’s bones, he responded: “I could well believe it. The French wanted Yeats’ corpse as a tourist attraction and they were determined the corpse would never go. Once the French have something, they never give it up.” The confusion over the remains of the poet began not long after his first burial. There was fighting and bombing close to the Roquebrune cemetery, destroying many burial records and graves. Yeats’ last lover, Edith Shakleton, said that she had visited his burial site. She learned that Yeats, and many others, had been moved to a pauper’s graveyard during the fighting. All bones were later dug up and placed in a communal ossuary. In a further complication, Mrs. Georgie Yeats thought she had bought a 10-year lease on the grave. Instead, it was a five-year one.

In 2015, the 150th anniversary of the poet’s birth, The Irish Times dramatically uncovered the sequence of events in France. It released contemporary documents which the French Foreign Ministry gave to the Irish Embassy in Paris in June of that year. These were the private archives of French diplomat Jacques Camílle, and they seemed to point conclusively to a Yeats coffin that contained no Yeats. An editorial in the newspaper wearily accepted the evidence. “The revelations in the French diplomatic correspondence seem to confirm that the bones sent back to Ireland in 1948 were not the poet’s.” It blamed the local French authorities in Roquebrune for the debacle. Yet it suggested that the sad news was irrelevant, for the heart, soul and poetry of Yeats belonged only to his native county. “In the natural grandeur of Sligo, the poet found an inspiration that lit up his verse with a burning flame,” it said. A British Yeats scholar commented that “the grave is a shrine, and shrines are about stones, not bones. Their symbolic significance designedly outlives human remains.”

Before the W.B. Yeats coffin had left France, the poet’s friends knew the remains had been scattered into an ossuary in 1946 and advised his widow Georgie against the repatriation. But the tectonic plates of Irish politics were already carrying the issue forward. Literary figures had been sniping occasionally at Irish leader Eamonn de Valera for failing to bring the Nobel laureate home. In 1948, de Valera’s government collapsed. It was replaced by an inter-party coalition, led by John Costello, and with Sean McBride as foreign minister. McBride was none other than the son of Maud Gonne, the woman and personal muse whom Yeats had loved all his life, but who had turned down his many proposals. McBride’s father John, Maud’s husband, had been executed for his part in the 1916 Easter Rising against the British. In his poem Easter 1916, Yeats ungraciously described his rival John McBride as “A drunken, vainglorious lout. / He had done most bitter wrong / To some who are near my heart” – a reference to some gossip that McBride had abused Maud. But the poem does go on to praise John McBride’s heroism as a rebel leader: “He, too, has been changed in his turn, / Transformed utterly: / A terrible beauty is born.”

The young McBride saw a chance to undercut de Valera, whom he disliked, by bringing Yeats back to Ireland in a blaze of national pride. He planned a magnificent funeral that would also link his mother’s name forever with the poet. The Yeats family, all de Valera loyalists, were not at all happy with these strands of McBride’s agenda. There was an intense mutual dislike between the widow Georgie and the muse Maud. In September 2018, the Irish broadcaster RTÉ aired a radio documentary to commemorate the repatriation and Drumcliffe funeral of W.B. Yeats. The presenter, John Bowman, broadcast rare archive recordings of the event and of those who attended. One of these was the rakish O’Mahoney, who was at the dockside in Galway harbour when the remains arrived.

“The dream of the McBrideite section of the Cabinet who favoured a state funeral was that an Irish naval corvette was to go through the Straits of Gibraltar and past Toulon, and collect the body, and come back,” O’Mahoney recalled. “Now they were to come direct to Sligo, the remains were to come direct to Sligo. The Yeats family intimated that they would not tolerate this. There had to be a state service at St. Patrick’s Cathedral [in Dublin], and then a magnificent donkey derby across Ireland and interment in Sligo. Mrs. Yeats put her foot down, along with [brother] Jack Yeats, who was very pro-DeValera; they prohibited it. They said that Yeats belonged to Sligo, he did not belong to Dublin (although he did). The remains were to go to Sligo direct by boat, and then the Sligo Corporation were to do what they liked with him – he was Sligo’s property.” O’Mahoney paused, claiming he would now reveal a state secret. “I’m telling state secrets, which I elicited at a Patrick’s Day banquet in St. Louis. The Irish Navy, if you please, certified that there was not sufficient draft in Sligo harbour for the empty boat to come in. Such a terrible slur on the Irish ports I never heard and I asked a distinguished naval officer if this was true, and he told me it was. They, the plotters and planners, were determined that the corpse would not come to Sligo, to spite Mrs. Yeats. And they certified that there was insufficient draft. … So the anti-McBride-ites and the Yeats-ites had to give in, and the compromise then was Galway harbour.”

Despite the background sniping and intrigue, the 130-km-drive of the cortege from Galway to Sligo and the interment in Drumcliffe churchyard was a moving national event. “A joyful occasion,” O’Mahoney declared. “I can’t imagine any greater funeral in Ireland except for [Charles Stuart] Parnell and Michael Collins. When we reached the county border of Sligo, we were met by the mayor, and the mayor simply said, “William Butler Yeats, welcome to Sligo.” In the RTÉ documentary, a reporter broadcast from the town: “Led by a pipers band playing a lament, the cortege moved into the town of Sligo – Yeatstown – and took over an hour to pass through the streets lined with crowds, all shops closed and shuttered, all work at a standstill.” Government officials, family and friends of Yeats, and celebrities from Ireland’s literary and artistic elites were there. They included the directors of the Abbey Theatre, which Yeats had co-founded in Dublin with his friend and patron, Lady Augusta Gregory. But it was clear that Yeats was loved and admired by all his countrymen and women.

“The plain people of Ireland, God bless them, crowded around, looking on,” said O’Mahoney. “Looking on. They wouldn’t come into the Protestant cemetery, d’you see. They were on the ditch all around, and they said a decade of the [Catholic] rosary for the repose of his soul. And I’m sure on the other side of the thunder, he felt that was as great a tribute as he could have got. And then, we interred him, and it was all over.”

The documentary made a brief mention of the controversy of the bones. “There’s a further twist to the story,” said Bowman. “It is now contended that the remains which came back from France may not have been those of Yeats at all.” The 2015 French documents are powerful evidence that the bones gathered in Roquebrune were a haphazard collection. Bernard Cailloux, the French diplomat, went there to locate Yeats’ missing remains in March 1948. He wrote that “it was impossible to return the full and authentic remains of Mr. Yeats.” A local sworn pathologist, Dr. Rebouillat, was asked “to reconstitute a skeleton presenting all the characteristics of the deceased.”

Bowman’s passing mention of the controversy on the funeral anniversary is typical of the attitude in Ireland. The Yeats family, the establishment, and the Sligo tourism industry would rather keep their hands over their ears than hear any new facts. One visiting lecturer on the subject in Sligo was angrily attacked in a local newspaper headline: “Who is this man and why is he trying to destroy our tourist industry?” – even though the lecturer said all his information came from exhibits at Sligo Museum. Of course, the obvious answer to any questions about the Yeats remains is now at hand – DNA analysis. “Irish officials shudder at the mere mention of DNA,” wrote Lara Marlowe, in the Irish Times report on the French documents. It will never happen.

Yeats family descendants still stand by a detailed 7-point letter the poet’s son and daughter wrote to the Times in October 1988. They utterly refuted any idea that the body in Drumcliffe was not Yeats. After detailing strict measures they took to bring the correct body to Ireland, the letter concludes: “There is indeed nothing to discuss, since we are satisfied beyond doubt that our father’s body is indeed buried in Drumcliffe churchyard.” When the Times contacted Caitriona Yeats, the poet’s granddaughter and closest surviving relative, about the 2015 French documents, she declined to comment. She again referred the reporter to the 1988 letter. Hands over ears, and la-la-la-la, indeed.

At the 1948 Sligo funeral, the town’s mayor said: “Today, we have fulfilled the express desires of W.B. Yeats, that he might rest in the shelter of Ben Bulben … Let the epitaph he wrote now be inscribed on stone. ‘Cast a cold Eye on Life, on Death. Horseman, pass by’.” Perhaps the time has come to amend those famous enigmatic lines:

“Horseman, pass by. Nothing to see here.”