Benedict Carey in The New York Times:

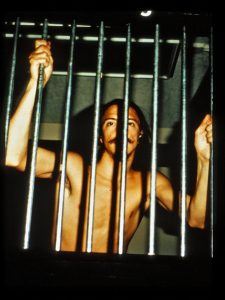

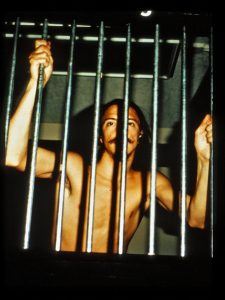

The Stanford prison experiment is a case in point. In the summer of 1971, Philip Zimbardo, a midcareer psychologist, recruited 24 college students through newspaper ads and randomly cast half of them as “prisoners” and half as “guards,” setting them up in a mock prison, compete with cells and uniforms. He had the simulation filmed. After six days, Dr. Zimbardo called the experiment off, reporting that the “guards” began to assume their roles too well. They became abusive, some of them shockingly so. Dr. Zimbardo published dispatches about the experiment in a couple of obscure journals. He provided a more complete report in an article he wrote in The New York Times, describing how cruel instincts could emerge spontaneously in ordinary people as a result of situational pressures and expectations. That article and “Quiet Rage,” a documentary about the experiment, helped make Dr. Zimbardo a star in the field and media favorite, most recently in the wake of the Abu Ghraib prison scandal in the early 2000s.

The Stanford prison experiment is a case in point. In the summer of 1971, Philip Zimbardo, a midcareer psychologist, recruited 24 college students through newspaper ads and randomly cast half of them as “prisoners” and half as “guards,” setting them up in a mock prison, compete with cells and uniforms. He had the simulation filmed. After six days, Dr. Zimbardo called the experiment off, reporting that the “guards” began to assume their roles too well. They became abusive, some of them shockingly so. Dr. Zimbardo published dispatches about the experiment in a couple of obscure journals. He provided a more complete report in an article he wrote in The New York Times, describing how cruel instincts could emerge spontaneously in ordinary people as a result of situational pressures and expectations. That article and “Quiet Rage,” a documentary about the experiment, helped make Dr. Zimbardo a star in the field and media favorite, most recently in the wake of the Abu Ghraib prison scandal in the early 2000s.

Perhaps the central challenge to the study’s claims is that its author coached the “guards” to be hard cases. Is this coaching “not an overt invitation to be abusive in all sorts of psychological ways?” wrote Peter Gray, a psychologist at Boston College who decided to exclude any mention of the simulation from his popular introductory textbook. “And, when the guards did behave in these ways and escalated that behavior, with Zimbardo watching and apparently (by his silence) approving, would that not have confirmed in the subjects’ minds that they were behaving as they should?”

Recent challenges have echoed Dr. Gray’s, and earlier this month Dr. Zimbardo was moved to post a response online.“My instructions to the guards, as documented by recordings of guard orientation, were that they could not hit the prisoners but could create feelings of boredom, frustration, fear and a sense of powerlessness — that is, ‘we have total power of the situation and they have none,’” he wrote. “We did not give any formal or detailed instructions about how to be an effective guard.” In an interview, Dr. Zimbardo said that the simulation was a “demonstration of what could happen” to some people influenced by powerful social roles and outside pressures, and that his critics had missed this point.

Which argument is more persuasive depends to some extent on where you sit and what you may think of Dr. Zimbardo. Is it better to describe his experiment, questions and all — or to ignore it entirely as not real psychology?

More here.

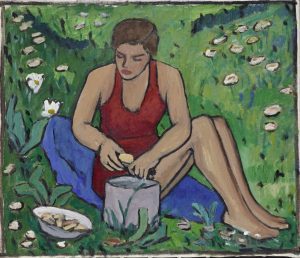

The idea behind the career-spanning exhibition of Gabriele Münter at the Louisiana is to take a woman who should be one of Germany’s most famous artists and to break her free from Kandinsky—here, she is presented as an artist, separately and simply. Isabelle Jansen, the show’s curator, notes in her recent book on Münter that “through the narrow lens of her relationship with Kandinsky many of her accomplishments have lingered in obscurity.” Jansen hopes to approach “Münter’s oeuvre in all its richness: from classic genres such as portraits and landscapes to interiors, abstractions, and her works of ‘primitivism.’ ”

The idea behind the career-spanning exhibition of Gabriele Münter at the Louisiana is to take a woman who should be one of Germany’s most famous artists and to break her free from Kandinsky—here, she is presented as an artist, separately and simply. Isabelle Jansen, the show’s curator, notes in her recent book on Münter that “through the narrow lens of her relationship with Kandinsky many of her accomplishments have lingered in obscurity.” Jansen hopes to approach “Münter’s oeuvre in all its richness: from classic genres such as portraits and landscapes to interiors, abstractions, and her works of ‘primitivism.’ ”

George Orwell conjured up a totalitarian regime where Ignorance Is Strength, but he surely never conceived of this. How can we know that two and two make four, or that the DNC isn’t responsible for its own hacking, or that Vladimir Putin isn’t a bigger American friend than the entire European Union and Nato alliance? As Trump explained so clearly, when he talks about Russia as a rival, he really means it as a compliment, no matter what your lying ears have told you.

George Orwell conjured up a totalitarian regime where Ignorance Is Strength, but he surely never conceived of this. How can we know that two and two make four, or that the DNC isn’t responsible for its own hacking, or that Vladimir Putin isn’t a bigger American friend than the entire European Union and Nato alliance? As Trump explained so clearly, when he talks about Russia as a rival, he really means it as a compliment, no matter what your lying ears have told you. The Stanford prison experiment is a case in point. In the summer of 1971, Philip Zimbardo, a midcareer psychologist, recruited 24 college students through newspaper ads and randomly cast half of them as “prisoners” and half as “guards,” setting them up in a mock prison, compete with cells and uniforms. He had the simulation filmed. After six days, Dr. Zimbardo called the experiment off, reporting that the “guards” began to assume their roles too well. They became abusive, some of them shockingly so. Dr. Zimbardo published dispatches about the experiment in a couple of obscure journals. He provided a more complete report in an article he wrote in The New York Times, describing how cruel instincts could emerge spontaneously in ordinary people as a result of situational pressures and expectations. That article and “Quiet Rage,” a documentary about the experiment, helped make Dr. Zimbardo a star in the field and media favorite, most recently in the wake of the Abu Ghraib prison scandal in the early 2000s.

The Stanford prison experiment is a case in point. In the summer of 1971, Philip Zimbardo, a midcareer psychologist, recruited 24 college students through newspaper ads and randomly cast half of them as “prisoners” and half as “guards,” setting them up in a mock prison, compete with cells and uniforms. He had the simulation filmed. After six days, Dr. Zimbardo called the experiment off, reporting that the “guards” began to assume their roles too well. They became abusive, some of them shockingly so. Dr. Zimbardo published dispatches about the experiment in a couple of obscure journals. He provided a more complete report in an article he wrote in The New York Times, describing how cruel instincts could emerge spontaneously in ordinary people as a result of situational pressures and expectations. That article and “Quiet Rage,” a documentary about the experiment, helped make Dr. Zimbardo a star in the field and media favorite, most recently in the wake of the Abu Ghraib prison scandal in the early 2000s.

For someone who spent most of his life trying to get on Page Six, (the New York Post’s iconic gossip column), hitting Page One was pay dirt for Donald Trump. Now that he’s there, he means to stay there, devouring our attention for the foreseeable future. One could even argue that all his lies and deplorable actions are motivated by a single, sorry ambition, to be the center of attention at all times and in all places. Outrage sells.

For someone who spent most of his life trying to get on Page Six, (the New York Post’s iconic gossip column), hitting Page One was pay dirt for Donald Trump. Now that he’s there, he means to stay there, devouring our attention for the foreseeable future. One could even argue that all his lies and deplorable actions are motivated by a single, sorry ambition, to be the center of attention at all times and in all places. Outrage sells. Four years ago, Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International—joining hundreds of others—urged the United Nations Security Council to send atrocity crimes committed in Syria to the International Criminal Court (ICC) for prosecution. Then, the conflict had already claimed 100,000 lives, overwhelmingly civilians. Today, the death toll is estimated at over half a million, with each day bringing new violations and unlawful killings.

Four years ago, Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International—joining hundreds of others—urged the United Nations Security Council to send atrocity crimes committed in Syria to the International Criminal Court (ICC) for prosecution. Then, the conflict had already claimed 100,000 lives, overwhelmingly civilians. Today, the death toll is estimated at over half a million, with each day bringing new violations and unlawful killings. The obelisk bearing the chiseled gray-granite face of a Confederate soldier enters my field of vision each morning as I stroll across campus. After forty years away from Mississippi, I returned last year to teach at my alma mater, Ole Miss. Having entered the University of Mississippi in 1974, only twelve years after James Meredith shattered the color barrier, I was one of about fifty black students in a freshman class of more than 800, African Americans then making up less than 5 percent of the entire student body.

The obelisk bearing the chiseled gray-granite face of a Confederate soldier enters my field of vision each morning as I stroll across campus. After forty years away from Mississippi, I returned last year to teach at my alma mater, Ole Miss. Having entered the University of Mississippi in 1974, only twelve years after James Meredith shattered the color barrier, I was one of about fifty black students in a freshman class of more than 800, African Americans then making up less than 5 percent of the entire student body. In Tamil, farewells are never final. As Akil Kumarasamy pointed out in a 2017 interview, the Tamil equivalent of goodbye is poyittu varen, meaning “I’ll go and return.” These are parting words especially suited to the refugee: ever running away, ever looking back.

In Tamil, farewells are never final. As Akil Kumarasamy pointed out in a 2017 interview, the Tamil equivalent of goodbye is poyittu varen, meaning “I’ll go and return.” These are parting words especially suited to the refugee: ever running away, ever looking back. Last month, the artificial intelligence company DeepMind

Last month, the artificial intelligence company DeepMind  On Sunday night,

On Sunday night,  ALAN BEAM WAS

ALAN BEAM WAS  Identity politics has engulfed the humanities and social sciences on American campuses; now it is taking over the hard sciences. The STEM fields—science, technology, engineering, and math—are under attack for being insufficiently “diverse.” The pressure to increase the representation of females, blacks, and Hispanics comes from the federal government, university administrators, and scientific societies themselves. That pressure is changing how science is taught and how scientific qualifications are evaluated. The results will be disastrous for scientific innovation and for American competitiveness.

Identity politics has engulfed the humanities and social sciences on American campuses; now it is taking over the hard sciences. The STEM fields—science, technology, engineering, and math—are under attack for being insufficiently “diverse.” The pressure to increase the representation of females, blacks, and Hispanics comes from the federal government, university administrators, and scientific societies themselves. That pressure is changing how science is taught and how scientific qualifications are evaluated. The results will be disastrous for scientific innovation and for American competitiveness.