David Remnick in The New Yorker:

In dictatorial states, a failure to applaud the Leader has often been a matter of treason. Last February, following the State of the Union address, President Trump flew to Blue Ash, Ohio, for a rally and accused the Democrats in Congress of that very crime. Their crime was a failure to stand and applaud sufficiently for the President of the United States. “You’re up there and you’ve got half the room going totally crazy, wild—they loved everything, they want to do something great for our country,” Trump said. “And you have the other side, even on positive news . . . they were like death and un-American. Un-American. Somebody said, ‘treasonous.’ I mean, yeah, I guess, why not? Can we call that treason? Why not? I mean, they certainly didn’t seem to love our country very much.”

In dictatorial states, a failure to applaud the Leader has often been a matter of treason. Last February, following the State of the Union address, President Trump flew to Blue Ash, Ohio, for a rally and accused the Democrats in Congress of that very crime. Their crime was a failure to stand and applaud sufficiently for the President of the United States. “You’re up there and you’ve got half the room going totally crazy, wild—they loved everything, they want to do something great for our country,” Trump said. “And you have the other side, even on positive news . . . they were like death and un-American. Un-American. Somebody said, ‘treasonous.’ I mean, yeah, I guess, why not? Can we call that treason? Why not? I mean, they certainly didn’t seem to love our country very much.”

It’s unlikely that anyone remembers that moment in Blue Ash—a moment that would be an enduring stain on any other President—and the reason is obvious: Trump’s penchant for bald deception and incoherence is not an aberration. It is his daily practice. The vague sense of torpor and gloom that so many Americans have shouldered these past two years derives precisely from the constancy of Trump’s galling statements and actions.

And yet what happened in Helsinki on Monday will not be so easily forgotten. Just as the President’s comments following the torchlit white-supremacist march last year in Charlottesville made it clear that racism was at the core of his character and his political strategy, the contemptible remarks he delivered alongside of Vladimir Putin seemed to mark a turning point, even for some of his most ardent defenders. In the course of a single European journey, Trump set out to humiliate the leaders of Western Europe and declare them “foes”; to fracture long-standing military, economic, and political alliances; and to absolve Russia of its attempts to undermine the 2016 election. He did so clearly, repeatedly, and with conviction. Republicans in Congress (but not enough of them) and a selection of commentators on Fox News declared that Trump’s performance in Helsinki had been disgraceful.

The President’s attempt to reverse the damage—clearly the result of a panicked White House staff—only worsened the matter. Speaking from the White House Cabinet Room on Tuesday, Trump tried to take his listeners for fools as he explained that he had merely been misunderstood by the press. This was one of the most shameless walk-back attempts in the history of the American Presidency. Reading from prepared notes, which always lends to his delivery a hostage-like cadence, Trump tried to half-apologize to the American intelligence community for equating its analysis with that of Putin and the F.S.B. And, with that, the lights suddenly went out. The President sat in darkness. Even before the worldwide commentariat had a chance to voice its incredulity, the White House electrical system had called bullshit on Trump. Or was it a higher power?

More here.

Martin Heidegger’s writings owe their fascination to their fusion of radical criticism of the Western philosophical tradition with a dark, trenchant diagnosis of the “homelessness” and “destitute” condition of human beings in modernity. Heidegger’s work has enjoyed unrivalled influence in a wide range of twentieth-century philosophical movements or fields – phenomenology and existentialism, pragmatism and postmodernism, hermeneutics and poetics, theology and environmental ethics. Phenomenologists and pragmatists could applaud his “destruction” of Cartesian rationalism, existentialists his call to “authenticity”, and environmentalists his reflections on “the devastation of the earth”. Heidegger’s influence might have been greater still if potential admirers had not been deterred by his challenging vocabulary or by his connection to Nazism.

Martin Heidegger’s writings owe their fascination to their fusion of radical criticism of the Western philosophical tradition with a dark, trenchant diagnosis of the “homelessness” and “destitute” condition of human beings in modernity. Heidegger’s work has enjoyed unrivalled influence in a wide range of twentieth-century philosophical movements or fields – phenomenology and existentialism, pragmatism and postmodernism, hermeneutics and poetics, theology and environmental ethics. Phenomenologists and pragmatists could applaud his “destruction” of Cartesian rationalism, existentialists his call to “authenticity”, and environmentalists his reflections on “the devastation of the earth”. Heidegger’s influence might have been greater still if potential admirers had not been deterred by his challenging vocabulary or by his connection to Nazism.

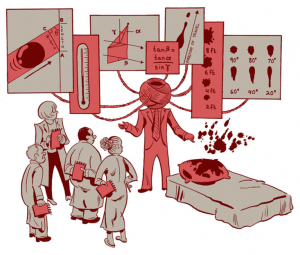

By the time Donald Johnson got the call to come to the crime scene, the victim had been dead for hours. A first responder opened the apartment door to find a woman lying on the edge of her bed, nude from the waist down, bound and gagged with duct tape. She had been bludgeoned to death. The homicide detectives needed an expert to gather the evidence. That was where Johnson came in. Then a senior criminalist for the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, Johnson surveyed the apartment. Shards of ceramic lay on the kitchen floor, remnants from a broken jar that once held flour. Johnson noticed two sets of footprints in the flour, ignaling to him that there were two assailants. Clothes spilled from a chest against the wall across from the bed. From the mangled lock, Johnson could tell the chest had been forcibly opened, perhaps with a crowbar. There was also blood on the lock, with a trail of drops on the floor leading to the sink where the assailant had washed his hands.

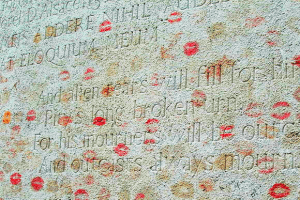

By the time Donald Johnson got the call to come to the crime scene, the victim had been dead for hours. A first responder opened the apartment door to find a woman lying on the edge of her bed, nude from the waist down, bound and gagged with duct tape. She had been bludgeoned to death. The homicide detectives needed an expert to gather the evidence. That was where Johnson came in. Then a senior criminalist for the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, Johnson surveyed the apartment. Shards of ceramic lay on the kitchen floor, remnants from a broken jar that once held flour. Johnson noticed two sets of footprints in the flour, ignaling to him that there were two assailants. Clothes spilled from a chest against the wall across from the bed. From the mangled lock, Johnson could tell the chest had been forcibly opened, perhaps with a crowbar. There was also blood on the lock, with a trail of drops on the floor leading to the sink where the assailant had washed his hands. Nearly 120 years after his death, Oscar Wilde’s works continue to delight with their brilliant paradoxes and comic twists. His children’s stories, poems and political essays captivate us today just as they captivated his contemporary audience. The Picture of Dorian Gray has become a haunting classic. And a successful season of his plays at the Vaudeville Theatre culminates with Wilde’s greatest work, The Importance of Being Earnest, which starts on 20th July.

Nearly 120 years after his death, Oscar Wilde’s works continue to delight with their brilliant paradoxes and comic twists. His children’s stories, poems and political essays captivate us today just as they captivated his contemporary audience. The Picture of Dorian Gray has become a haunting classic. And a successful season of his plays at the Vaudeville Theatre culminates with Wilde’s greatest work, The Importance of Being Earnest, which starts on 20th July. Among Africa’s poorest countries, Togo is surrounded by better-off neighbors that for decades have struggled to defeat lymphatic filariasis, a tropical disease commonly known as

Among Africa’s poorest countries, Togo is surrounded by better-off neighbors that for decades have struggled to defeat lymphatic filariasis, a tropical disease commonly known as  Leave America, and you begin to see it as the rest of the world sees it: as an unpredictable, potentially hostile force dedicated exclusively to protecting its own interests; as a gargantuan military power with an aggressive presence on the world stage and a dangerously undereducated populace. We’ve toppled governments, covertly assassinated democratically elected leaders, waged illegal wars that have poisoned and destabilized entire regions around the globe. The enormous postwar bonus we’ve enjoyed—our status as the world’s darlings—has been eroding steadily away, yet incredibly, we still imagine that everyone loves us. Peering wide-eyed from our self-absorbed bubble, we issue Facebook “apologies” to the rest of the world for our mortifying president and his absurd coterie, not quite realizing that the world, at this point, is less interested in how Americans feel than in foreseeing, assessing, and coping with the damage the United States is likely to wreak on world peace, stability, economic justice, and the environment.

Leave America, and you begin to see it as the rest of the world sees it: as an unpredictable, potentially hostile force dedicated exclusively to protecting its own interests; as a gargantuan military power with an aggressive presence on the world stage and a dangerously undereducated populace. We’ve toppled governments, covertly assassinated democratically elected leaders, waged illegal wars that have poisoned and destabilized entire regions around the globe. The enormous postwar bonus we’ve enjoyed—our status as the world’s darlings—has been eroding steadily away, yet incredibly, we still imagine that everyone loves us. Peering wide-eyed from our self-absorbed bubble, we issue Facebook “apologies” to the rest of the world for our mortifying president and his absurd coterie, not quite realizing that the world, at this point, is less interested in how Americans feel than in foreseeing, assessing, and coping with the damage the United States is likely to wreak on world peace, stability, economic justice, and the environment. The human mind loves nothing more than to build mental boxes — categories — and put things into them, then refuse to accept it when something doesn’t fit. Nowhere is this more clear than in the idea that there are men, and there are women, and that’s it. Alice Dreger is an historian of science, specializing in intersexuality and the relationship between bodies and identities. She is also a successful activist, working to change the way that doctors deal with newborn children who are born intersex. We talk about human sexuality and a number of other hot-button topics, and ruminate on the challenges of being both an intellectual (devoted to truth) and an activist (seeking justice).

The human mind loves nothing more than to build mental boxes — categories — and put things into them, then refuse to accept it when something doesn’t fit. Nowhere is this more clear than in the idea that there are men, and there are women, and that’s it. Alice Dreger is an historian of science, specializing in intersexuality and the relationship between bodies and identities. She is also a successful activist, working to change the way that doctors deal with newborn children who are born intersex. We talk about human sexuality and a number of other hot-button topics, and ruminate on the challenges of being both an intellectual (devoted to truth) and an activist (seeking justice). A

A No matter how much her projects vary in tone, style, and subject matter, Haenel always adjusts the temperature. Languorous and narcotic,

No matter how much her projects vary in tone, style, and subject matter, Haenel always adjusts the temperature. Languorous and narcotic,

In dictatorial states, a failure to applaud the Leader has often been a matter of treason. Last February, following the

In dictatorial states, a failure to applaud the Leader has often been a matter of treason. Last February, following the  While Americans are well-acquainted with Russian online trolls’ 2016 disinformation campaign, there’s a more insidious threat of Russian interference in the coming midterms. The Russians could hack our very election infrastructure, disenfranchising Americans and even altering the vote outcome in key states or districts. Election security experts have warned of it, but state election officials have largely played it down for fear of spooking the public. We still might not know the extent to which state election infrastructure was compromised in 2016, nor how compromised it will be in 2018.

While Americans are well-acquainted with Russian online trolls’ 2016 disinformation campaign, there’s a more insidious threat of Russian interference in the coming midterms. The Russians could hack our very election infrastructure, disenfranchising Americans and even altering the vote outcome in key states or districts. Election security experts have warned of it, but state election officials have largely played it down for fear of spooking the public. We still might not know the extent to which state election infrastructure was compromised in 2016, nor how compromised it will be in 2018. Some environmentalists believe countries should somehow rely on renewables alone to increase their energy supply. Renewables — primarily wind and solar — certainly have a place in the mix, especially locally and at small scale. But because larger-scale renewable sources are dispersed and dilute, they’re limited to favorable conditions, and since they’re intermittent, they require backup energy generation to fill in when the wind doesn’t blow or the sun doesn’t shine.

Some environmentalists believe countries should somehow rely on renewables alone to increase their energy supply. Renewables — primarily wind and solar — certainly have a place in the mix, especially locally and at small scale. But because larger-scale renewable sources are dispersed and dilute, they’re limited to favorable conditions, and since they’re intermittent, they require backup energy generation to fill in when the wind doesn’t blow or the sun doesn’t shine. Why should we mourn the death of a bad person? I was recently struck by an interesting philosophical conversation on death that emerged far outside of the philosophy classroom—on Twitter. Hip-hop fans were grappling with the

Why should we mourn the death of a bad person? I was recently struck by an interesting philosophical conversation on death that emerged far outside of the philosophy classroom—on Twitter. Hip-hop fans were grappling with the  There’s always been a drumbeat of disapproval of Plath’s work, and it often comes down to: She’s just too much.

There’s always been a drumbeat of disapproval of Plath’s work, and it often comes down to: She’s just too much.