by Michael Liss

The other shoe dropped.

Anthony Kennedy’s idiosyncratic role as a Justice of the United State Supreme Court will come to an end a mere week from now. A lot of things are going to change.

Let’s start with the politics. Kennedy’s leaving cinches the conservative revolution (or counter-revolution) for at least a generation. For the first time in living memory, a conservative Supreme Court will be in position to review and bless the acts of a like-minded Congress and President.

This will occur regardless of who is confirmed (Trump’s list is one to which moderates need not apply), but, unless a bolt of lightning strikes, it’s going to be Brett Kavanaugh. Yes, there will be plenty of Kabuki before he gets measured for a new robe, but Kavanaugh is the one who rings every bell for both Republicans and Trump. He’s a Federalist Society member, reliably conservative on all the big issues, not afraid to advance his interpretation of the law even when it conflicts with precedent, and has a past history of partisan politics. His nomination even offers a prize in the Cracker Jack box—the unique, magnificent straddle of having worked aggressively for Ken Starr, but now being deeply committed to the idea that sitting Presidents should be immune from prosecution. Read more »

Spectator sports can reflect a society’s worst inclinations by promoting pure partisanship.

Spectator sports can reflect a society’s worst inclinations by promoting pure partisanship.

Although some may be heralding the end of free speech, 2018 has been a year of far-reaching debate and discussion. In the coming months, we can anticipate attending or streaming discussions ranging from such topics as the role of race in American politics to the nature of truth, from existential threats posed by artificial intelligence to the value of religion.

Although some may be heralding the end of free speech, 2018 has been a year of far-reaching debate and discussion. In the coming months, we can anticipate attending or streaming discussions ranging from such topics as the role of race in American politics to the nature of truth, from existential threats posed by artificial intelligence to the value of religion. What are you doing? I don’t mean what are you doing with your life, or in general, but what are you doing right now? The answer, in one respect, is simple enough: you’re reading this magazine. Obviously. From a certain economic perspective, however, you’re doing something else, something you don’t realize, something with a sneaky motive that you aren’t admitting to yourself: you are signalling. You are sending signals about the kind of person you are, or want to be. What’s that you say—you’re reading this in the bath, or on your phone in bed, or otherwise in private? Well, the same argument applies. You are acquiring the tools for a “fitness display.” This, the economist Robin Hanson and the writer-programmer Kevin Simler argue in their new book, “

What are you doing? I don’t mean what are you doing with your life, or in general, but what are you doing right now? The answer, in one respect, is simple enough: you’re reading this magazine. Obviously. From a certain economic perspective, however, you’re doing something else, something you don’t realize, something with a sneaky motive that you aren’t admitting to yourself: you are signalling. You are sending signals about the kind of person you are, or want to be. What’s that you say—you’re reading this in the bath, or on your phone in bed, or otherwise in private? Well, the same argument applies. You are acquiring the tools for a “fitness display.” This, the economist Robin Hanson and the writer-programmer Kevin Simler argue in their new book, “ The priest quickly sliced into the captive’s torso and removed his still-beating heart. That sacrifice, one among thousands performed in the sacred city of Tenochtitlan, would feed the gods and ensure the continued existence of the world.

The priest quickly sliced into the captive’s torso and removed his still-beating heart. That sacrifice, one among thousands performed in the sacred city of Tenochtitlan, would feed the gods and ensure the continued existence of the world. Some time back I took a group of students to the Galerie d’Anatomie Comparée at the Jardin des Plantes. This is the famous collection of skeletons laid out according to one version of the order of nature by Georges Cuvier at the turn of the 19th century. We were looking at a display case (added long after Cuvier’s death) that consisted in four rows, one above the other, with five skulls in each row representing five developmental stages of three species of great ape –gorillas, chimpanzees, and orangutans–, plus Homo sapiens.

Some time back I took a group of students to the Galerie d’Anatomie Comparée at the Jardin des Plantes. This is the famous collection of skeletons laid out according to one version of the order of nature by Georges Cuvier at the turn of the 19th century. We were looking at a display case (added long after Cuvier’s death) that consisted in four rows, one above the other, with five skulls in each row representing five developmental stages of three species of great ape –gorillas, chimpanzees, and orangutans–, plus Homo sapiens.  In 1765, Russian Empress Catherine the Great heard that the philosopher Dennis Diderot was in dire need of money. As a well-known patron of the arts, sciences, and Enlightenment philosophers, she immediately purchased his entire library. She directed him to keep it at his home and hired him as her librarian with 25 years of salary upfront.

In 1765, Russian Empress Catherine the Great heard that the philosopher Dennis Diderot was in dire need of money. As a well-known patron of the arts, sciences, and Enlightenment philosophers, she immediately purchased his entire library. She directed him to keep it at his home and hired him as her librarian with 25 years of salary upfront. If climate change, nuclear standoffs, Russian trolls, terrorist threats and Donald Trump in the White House don’t cause you feelings of impending doom, you might think about artificial intelligence. I’m not just referring to big-brained robots taking over civilization from us smaller-brained humans, but the more imminent possibility they’ll

If climate change, nuclear standoffs, Russian trolls, terrorist threats and Donald Trump in the White House don’t cause you feelings of impending doom, you might think about artificial intelligence. I’m not just referring to big-brained robots taking over civilization from us smaller-brained humans, but the more imminent possibility they’ll  It’s already happening. Robots and related forms of artificial intelligence are rapidly supplanting what remain of factory workers, call-center operators and clerical staff. Amazon and other online platforms are booting out retail workers. We’ll soon be saying goodbye to truck drivers, warehouse personnel and professionals who do whatever can be replicated, including pharmacists, accountants, attorneys, diagnosticians, translators and financial advisers. Machines may soon do a

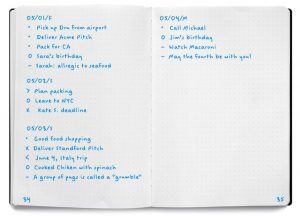

It’s already happening. Robots and related forms of artificial intelligence are rapidly supplanting what remain of factory workers, call-center operators and clerical staff. Amazon and other online platforms are booting out retail workers. We’ll soon be saying goodbye to truck drivers, warehouse personnel and professionals who do whatever can be replicated, including pharmacists, accountants, attorneys, diagnosticians, translators and financial advisers. Machines may soon do a  So it is with organising my life. I have tried paper diaries, Google Calendar and to-do apps. No matter the form, what they all have in common is a rigid structure imposed from above. You have a certain number of lines for each day or a finite number of categories into which your plans must fit, or a small palette of colours to highlight or distinguish between events. It drives me insane. So I made my own system: a Google spreadsheet with columns titled “today”, “tomorrow”, “this week”, “weekend”, “this month” and “three months”, and tabs to keep track of expenses, books I’ve read, travel plans, story ideas, and general note-keeping. It’s messy and entirely manual: there are no shortcuts, no functions, no add-ons.

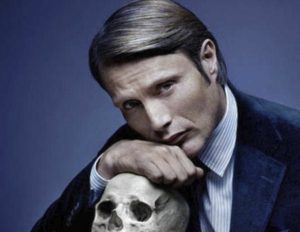

So it is with organising my life. I have tried paper diaries, Google Calendar and to-do apps. No matter the form, what they all have in common is a rigid structure imposed from above. You have a certain number of lines for each day or a finite number of categories into which your plans must fit, or a small palette of colours to highlight or distinguish between events. It drives me insane. So I made my own system: a Google spreadsheet with columns titled “today”, “tomorrow”, “this week”, “weekend”, “this month” and “three months”, and tabs to keep track of expenses, books I’ve read, travel plans, story ideas, and general note-keeping. It’s messy and entirely manual: there are no shortcuts, no functions, no add-ons. Begin, for once, with the ending: the arms at an awful angle, the face blue-lipped above a blot of blood. Only later do we glimpse the woman who corresponds to the corpse. She laughs in a flashback. Or she smiles in the photograph pinned to the board where the police map the murders with thumbtacks, charting tangled speculations with lines of yarn. In light of her death, she comes to life. This is the antiordering typical of the serial killer procedural, a narrative scramble that begins with the answer and ages back toward the question. In the television series Hannibal (NBC, 2013–15), a convicted murderer impales a nurse in prison. He snaps at the officers who come to question him, “I was caught red-handed. There’s no mystery as to who done it. I did it!” Still, the officers insist that they have something to ask.

Begin, for once, with the ending: the arms at an awful angle, the face blue-lipped above a blot of blood. Only later do we glimpse the woman who corresponds to the corpse. She laughs in a flashback. Or she smiles in the photograph pinned to the board where the police map the murders with thumbtacks, charting tangled speculations with lines of yarn. In light of her death, she comes to life. This is the antiordering typical of the serial killer procedural, a narrative scramble that begins with the answer and ages back toward the question. In the television series Hannibal (NBC, 2013–15), a convicted murderer impales a nurse in prison. He snaps at the officers who come to question him, “I was caught red-handed. There’s no mystery as to who done it. I did it!” Still, the officers insist that they have something to ask. For four seasons, Harvard professor Henry Louis Gates has been hosting the genealogy television show Finding Your Roots. In each episode, Mr. Gates presents celebrities with a book full of research into their ancestry, drawing from genealogical records and genetic tests. On a recent show, Mr. Gates introduced the actor Ted Danson to one of his 18th-century ancestors, Oliver Smith of Connecticut. Mr. Danson learned how Mr. Smith defended his seaside town against the British during the Revolutionary War.

For four seasons, Harvard professor Henry Louis Gates has been hosting the genealogy television show Finding Your Roots. In each episode, Mr. Gates presents celebrities with a book full of research into their ancestry, drawing from genealogical records and genetic tests. On a recent show, Mr. Gates introduced the actor Ted Danson to one of his 18th-century ancestors, Oliver Smith of Connecticut. Mr. Danson learned how Mr. Smith defended his seaside town against the British during the Revolutionary War. It isn’t tempting to write about Elon Musk in that it is easy but in that it is an event that few thought we could witness live: a successful businessman letting his true inner recklessness show. All that Musk has done is lose composure – but sadly for him, the window he opened into his mind exposed something unsavoury and disappointing. It is tempting to write about Musk because we can for once stop speculating about how it is that Silicon Valley entrepreneurs cut from the same cloth as Musk and Peter Thiel think, and take a break from amassing piles of secondhand, implicative evidence. Now we have proof – and an opportunity to characterise the psyche of this odiously powerful class of world society.

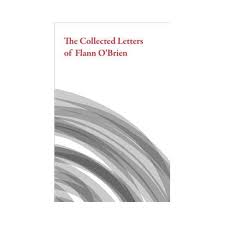

It isn’t tempting to write about Elon Musk in that it is easy but in that it is an event that few thought we could witness live: a successful businessman letting his true inner recklessness show. All that Musk has done is lose composure – but sadly for him, the window he opened into his mind exposed something unsavoury and disappointing. It is tempting to write about Musk because we can for once stop speculating about how it is that Silicon Valley entrepreneurs cut from the same cloth as Musk and Peter Thiel think, and take a break from amassing piles of secondhand, implicative evidence. Now we have proof – and an opportunity to characterise the psyche of this odiously powerful class of world society. In recent years, Flann O’Brien has often been characterised as the third member of the sacred trinity of Irish modernism, the Holy Ghost to James Joyce’s God the Father and Samuel Beckett’s God the Son. If so, he shares with the Holy Ghost a certain vagueness as to his identity: the press release that accompanies this book refers to him as ‘O’Nolan, or O’Brien, or Myles nagCopaleen or whatever his name may be’. Of these three personas, the first was a civil servant, the second a novelist and the third a satirical columnist for the Irish Times. Although they inhabited the same body, their relations were not always cordial: Flann O’Brien was effectively held hostage by his journalistic rival for two decades between the efflorescence of early novels and his re-emergence with The Hard Life (1961).

In recent years, Flann O’Brien has often been characterised as the third member of the sacred trinity of Irish modernism, the Holy Ghost to James Joyce’s God the Father and Samuel Beckett’s God the Son. If so, he shares with the Holy Ghost a certain vagueness as to his identity: the press release that accompanies this book refers to him as ‘O’Nolan, or O’Brien, or Myles nagCopaleen or whatever his name may be’. Of these three personas, the first was a civil servant, the second a novelist and the third a satirical columnist for the Irish Times. Although they inhabited the same body, their relations were not always cordial: Flann O’Brien was effectively held hostage by his journalistic rival for two decades between the efflorescence of early novels and his re-emergence with The Hard Life (1961). If a novel is especially immersive, if the voice of its narrator is sufficiently consistent and evocative, the world it describes may come to life in picturesque color. I say picturesque, rather than vivid, because a novel’s dominant colors may not be entirely lifelike; they may be closer to the rich oils of Rembrandt or the downy pastels of Degas. Such colors suggest life but also remind us of art’s mediating presence. Jacek Dehnel’s lush debut novel, Lala, for instance, is awash in the sepia tones of old photographs, a few of which punctuate the text. Like an old family album, assembled by an eccentric relative with an artistic bent, Dehnel’s work is drawn from life and enriched with intent, with a kind of aesthetic cohesion that bare facts lack.

If a novel is especially immersive, if the voice of its narrator is sufficiently consistent and evocative, the world it describes may come to life in picturesque color. I say picturesque, rather than vivid, because a novel’s dominant colors may not be entirely lifelike; they may be closer to the rich oils of Rembrandt or the downy pastels of Degas. Such colors suggest life but also remind us of art’s mediating presence. Jacek Dehnel’s lush debut novel, Lala, for instance, is awash in the sepia tones of old photographs, a few of which punctuate the text. Like an old family album, assembled by an eccentric relative with an artistic bent, Dehnel’s work is drawn from life and enriched with intent, with a kind of aesthetic cohesion that bare facts lack. John Edgar Wideman’s profound new book begins, as it must, with the American Civil War. The first story in this collection, “JB & FD” imagines a kind of conversation between two of the most important figures of that conflict, the white anti-slavery crusader John Brown, hanged in December 1859 for treason, murder, and inciting slave insurrection, and the black abolitionist Frederick Douglass, who had himself been born enslaved.

John Edgar Wideman’s profound new book begins, as it must, with the American Civil War. The first story in this collection, “JB & FD” imagines a kind of conversation between two of the most important figures of that conflict, the white anti-slavery crusader John Brown, hanged in December 1859 for treason, murder, and inciting slave insurrection, and the black abolitionist Frederick Douglass, who had himself been born enslaved.