Kathryn Hughes in The Guardian:

Over this ecstatic high summer, visitors to the Haworth parsonage museum will be able to watch a film that simulates the bird’s-eye view of Emily Brontë’s pet hawk, Nero, as he swoops over the moors to Top Withens, the ruined farmhouse that is the putative model for Wuthering Heights. You’ll be able to listen to the Unthanks, the quavery Northumbrian folk music sisters who have composed music in celebration of Emily’s 200th anniversary. If that’s not enough, you can watch a video installation by Lily Cole, the model-turned-actor-turned-Cambridge-double-first from Devon, which riffs on Heathcliff’s origins as a Liverpool foundling. Finally, Kate Bush, from Kent, has been busy on the moors unveiling a stone. In short, wherever you come from and whoever you are, you will find an Emily Brontë who is sufficiently formless yet endlessly adaptive to whatever you need her to be – a rock, a song, a bird in flight.

Over this ecstatic high summer, visitors to the Haworth parsonage museum will be able to watch a film that simulates the bird’s-eye view of Emily Brontë’s pet hawk, Nero, as he swoops over the moors to Top Withens, the ruined farmhouse that is the putative model for Wuthering Heights. You’ll be able to listen to the Unthanks, the quavery Northumbrian folk music sisters who have composed music in celebration of Emily’s 200th anniversary. If that’s not enough, you can watch a video installation by Lily Cole, the model-turned-actor-turned-Cambridge-double-first from Devon, which riffs on Heathcliff’s origins as a Liverpool foundling. Finally, Kate Bush, from Kent, has been busy on the moors unveiling a stone. In short, wherever you come from and whoever you are, you will find an Emily Brontë who is sufficiently formless yet endlessly adaptive to whatever you need her to be – a rock, a song, a bird in flight.

That’s assuming, of course, that you are female. Nearly all the activities mentioned in connection with the forthcoming anniversary of her birth on 30 July involve women as makers, demonstrators, celebrators and educators. Likewise, nearly all Emily Brontë’s biographers and scholars over the past century have been women. If you do spot a man in the mix, chances are that he has been shuffled off to the side, rather like Branwell Brontë, though hopefully without the urge to get drunk and set fire to himself. The only other author who has become the object of such an intense female pash in the last 200 years is Sylvia Plath, who happens to be buried less than 10 miles away from Haworth at Heptonstall. The parallels are uncanny. Separated by a century, both Brontë and Plath were poets who remain most famous for writing a single intensely autobiographical novel. There’s even a pleasing bit of intertextuality in the way that in 1956 Sylvia Plath actually managed to marry Heathcliff in the form of her own glowering man-of-the-moors, Ted Hughes. Together the newlyweds tramped up to Top Withins and wrote poems about it, an event that Hughes was still mulling over 40 years later in his valedictory Birthday Letters. Both Plath and Brontë died at the age of 30 and then only gradually started to attract the cult-like devotion of female fans, who responded rapturously to their heroines’ status as exiles from the twin kingdoms of heteronormative happiness and literary fame.

More here.

It was barely two hours into Day 1 of AlienCon and 500 years of accepted history and science were already being tossed out. Three thousand people had gathered inside the Civic Auditorium here for a panel discussion featuring presenters from “

It was barely two hours into Day 1 of AlienCon and 500 years of accepted history and science were already being tossed out. Three thousand people had gathered inside the Civic Auditorium here for a panel discussion featuring presenters from “

In 2014, a graduate student at the University of Waterloo, Canada, named

In 2014, a graduate student at the University of Waterloo, Canada, named  Carol Dweck, a psychology professor at Stanford University, remembers asking an undergraduate seminar recently, “How many of you are waiting to find your passion?”

Carol Dweck, a psychology professor at Stanford University, remembers asking an undergraduate seminar recently, “How many of you are waiting to find your passion?” Bilal Abdul Kareem is an expert in staying alive.

Bilal Abdul Kareem is an expert in staying alive.

Amitava Kumar in The Baffler:

Amitava Kumar in The Baffler: Early on in Helen Jukes’s A Honeybee Heart Has Five Openings she ponders the increasing popularity of urban beekeeping, referring to the idea that “one possible psychological response to the apprehension of a threat is to begin producing idealised versions of the thing we perceive of as being at risk”. That’s also a good explanation for the current crop of bee books: not just A Honeybee Heart and Thor Hanson’s Buzz, but Kate Bradbury’s wonderful The Bumblebee Flies Anyway and Maja Lunde’s The History of Bees, among others. Books, like hives, are ways of capturing something and holding on to it: either helping to preserve it, or looking at it closely before it’s gone.

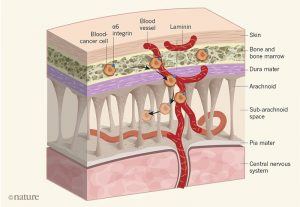

Early on in Helen Jukes’s A Honeybee Heart Has Five Openings she ponders the increasing popularity of urban beekeeping, referring to the idea that “one possible psychological response to the apprehension of a threat is to begin producing idealised versions of the thing we perceive of as being at risk”. That’s also a good explanation for the current crop of bee books: not just A Honeybee Heart and Thor Hanson’s Buzz, but Kate Bradbury’s wonderful The Bumblebee Flies Anyway and Maja Lunde’s The History of Bees, among others. Books, like hives, are ways of capturing something and holding on to it: either helping to preserve it, or looking at it closely before it’s gone. If malignant cells from solid or blood cancers enter the central nervous system (CNS) and grow there, the treatment options and clinical outlook deteriorate rapidly. In a type of leukaemia called acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL), invasion of the CNS commonly occurs. To try to limit this, people with the condition often receive radiation or chemotherapy that targets the CNS. If more-effective and less-toxic approaches became available to prevent disease spread to the CNS, this might benefit many people with ALL.

If malignant cells from solid or blood cancers enter the central nervous system (CNS) and grow there, the treatment options and clinical outlook deteriorate rapidly. In a type of leukaemia called acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL), invasion of the CNS commonly occurs. To try to limit this, people with the condition often receive radiation or chemotherapy that targets the CNS. If more-effective and less-toxic approaches became available to prevent disease spread to the CNS, this might benefit many people with ALL.  Sheri Berman in The Guardian:

Sheri Berman in The Guardian: In his book The Main Questions of Modern Culture from 1914, the German philosopher Emil Hammacher wrote about the questions of his time—among them the social, woman, and worker questions—their causes, and the longstanding desire to solve them and others, tracing their causes and solution-seeking back to

In his book The Main Questions of Modern Culture from 1914, the German philosopher Emil Hammacher wrote about the questions of his time—among them the social, woman, and worker questions—their causes, and the longstanding desire to solve them and others, tracing their causes and solution-seeking back to  CRISPR has been heralded as one of the

CRISPR has been heralded as one of the  Jamelle Bouie, the chief political correspondent for Slate, recently penned an essay suggesting that the Enlightenment was racist — though the real point seemed to be that liking the Enlightenment too much is kind of racist. Regardless, the essay set off quite a hullabaloo, mostly on Twitter. His main targets were two new books, Enlightenment Now, by Steven Pinker, and Suicide of the West, by yours truly. Jordan Peterson, the controversial Canadian psychologist bogeyman of the moment for many liberals, was namechecked for good measure.

Jamelle Bouie, the chief political correspondent for Slate, recently penned an essay suggesting that the Enlightenment was racist — though the real point seemed to be that liking the Enlightenment too much is kind of racist. Regardless, the essay set off quite a hullabaloo, mostly on Twitter. His main targets were two new books, Enlightenment Now, by Steven Pinker, and Suicide of the West, by yours truly. Jordan Peterson, the controversial Canadian psychologist bogeyman of the moment for many liberals, was namechecked for good measure. S

S Still, the application of the idea of the history of vision does not stop, and does not begin, with modernity. As Jonathan Crary argues at length, the general mode of perception may have undergone some important form of change already in the first half of the 19thcentury. And theorists of postmodernism rely on the principle of the history of vision as much as theorists of modernity do. Frederic Jameson, for example, argues that postmodernism offers “a whole new Utopian realm of the senses.” The premise all these arguments share is that history, and art history, can be understood, at least partially, as the history of perception. This assumption is so deeply ingrained in much of the discourse on 19th and 20th century art and culture and in (at least some branches of) art history and aesthetics that it has been taken for granted without further discussion. As Whitney Davis summarized, “according to visual-culture studies, it is true prima facie that vision has a cultural history.” And one of the guiding ideas of post-formalism has become the claim that vision (and imagination) has an (art) history.

Still, the application of the idea of the history of vision does not stop, and does not begin, with modernity. As Jonathan Crary argues at length, the general mode of perception may have undergone some important form of change already in the first half of the 19thcentury. And theorists of postmodernism rely on the principle of the history of vision as much as theorists of modernity do. Frederic Jameson, for example, argues that postmodernism offers “a whole new Utopian realm of the senses.” The premise all these arguments share is that history, and art history, can be understood, at least partially, as the history of perception. This assumption is so deeply ingrained in much of the discourse on 19th and 20th century art and culture and in (at least some branches of) art history and aesthetics that it has been taken for granted without further discussion. As Whitney Davis summarized, “according to visual-culture studies, it is true prima facie that vision has a cultural history.” And one of the guiding ideas of post-formalism has become the claim that vision (and imagination) has an (art) history.