Marta Figlerowicz in the Boston Review:

Immigrant life easily slips into melodrama. A whiff of blood sausage has me tearfully recalling the evenings when my grandmother cooked it for me. An unexpected “cześć,” or hello, overheard between two fellow Poles immerses me in involuntary memories, as I mourn greetings I shared with high school friends. I never actually liked blood sausage, or high school, and had rejoiced to leave them behind when I moved here. But for a moment, my unconscious fools me, and these recalled sensations compose themselves into a Hallmark card.

Immigrant life easily slips into melodrama. A whiff of blood sausage has me tearfully recalling the evenings when my grandmother cooked it for me. An unexpected “cześć,” or hello, overheard between two fellow Poles immerses me in involuntary memories, as I mourn greetings I shared with high school friends. I never actually liked blood sausage, or high school, and had rejoiced to leave them behind when I moved here. But for a moment, my unconscious fools me, and these recalled sensations compose themselves into a Hallmark card.

Most émigré writers gloss over such moments of weakness, depicting their attitudes and tastes as detached and worldly. Svetlana Boym (1959–2015), renowned scholar of comparative literature, was the rare thinker who leaned into them, in search for a more honest account of the uprooted life. “What might appear as an aestheticization of social existence to the ‘native,’” she wrote of such experiences, “strikes the immigrant as an accurate depiction of the condition of exile.” To be an immigrant is, paradoxically, not just to live in partial alienation from one’s new surroundings, but also to lose distance from the world one has left behind. It is only from such a position of humility, Boym further insisted, that illuminating generalizations about one’s experience—and about what this experience can teach others—can begin. As demonized and idealized depictions of migration loom large, Boym’s reflections on the fragilities of our memories in times of loss and transit seem more pressing than ever.

More here.

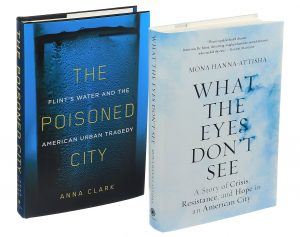

From the start, the people of Flint, Mich., knew something was wrong with the water coming out of their taps — it was brown and orange, visibly full of particles, frothy and foul-smelling. Their hair started falling out, and showers left their bodies burning with red welts. Their plants and pets began to die. On a hot day, children playing in the spray of a water hydrant were streaked with coffee-colored liquid.

From the start, the people of Flint, Mich., knew something was wrong with the water coming out of their taps — it was brown and orange, visibly full of particles, frothy and foul-smelling. Their hair started falling out, and showers left their bodies burning with red welts. Their plants and pets began to die. On a hot day, children playing in the spray of a water hydrant were streaked with coffee-colored liquid. Biased education poisons minds. The curriculum, textbooks, teachers and exams all act to create an ‘us’ versus ‘them’ mentality. Islam is shown as under siege by the evil West as well as India. And then there’s the electronic and print media – mostly privately owned – which drips with piety and with conspiracy theories that attribute all our ills to India, Israel and the United States. It seizes upon their every fault and then multiplies by ten. So a mindset is created wherein young people imagine that they, and their religion, are beset by enemies lurking behind every bush. The West is excoriated for being selective and hypocritical – which it surely is. But there’s no introspection, no explanation for how we went wrong. Ask a student why East Pakistan broke off to become Bangladesh and you’ll get the pat answer: it was a Hindu conspiracy. They won’t know of the genocide West Pakistan carried out there in 1971.

Biased education poisons minds. The curriculum, textbooks, teachers and exams all act to create an ‘us’ versus ‘them’ mentality. Islam is shown as under siege by the evil West as well as India. And then there’s the electronic and print media – mostly privately owned – which drips with piety and with conspiracy theories that attribute all our ills to India, Israel and the United States. It seizes upon their every fault and then multiplies by ten. So a mindset is created wherein young people imagine that they, and their religion, are beset by enemies lurking behind every bush. The West is excoriated for being selective and hypocritical – which it surely is. But there’s no introspection, no explanation for how we went wrong. Ask a student why East Pakistan broke off to become Bangladesh and you’ll get the pat answer: it was a Hindu conspiracy. They won’t know of the genocide West Pakistan carried out there in 1971. In 1973, a 22-year-old named Jonathan Richman wrote a letter to the editor of Creem. The Detroit magazine, which started in 1969 when both New Journalism and the archetype of the music critic were solidifying in the consciousness of American counterculture, was an iconic purveyor of rock ‘n’ roll criticism and culture. It had recently run a short, positive notice about Richman’s band, the Modern Lovers, whose fast, angry guitar music had given them a reputation in their native Boston. With its signature hopscotch of irony and humor, Creem synthesized the Lovers’ sound: “More than a little like a teenage Velvet Underground.” The magazine called one of their songs, “a guaranteed hit single” and another, “possibly the next national anthem.” Creem’s kidding aside, by most metrics, the Modern Lovers were in a good place in 1973. John Cale, legendary member of the Velvet Underground, was producing the Lovers’ debut album for Warner Brothers when their singer decided to write a letter to Creem.

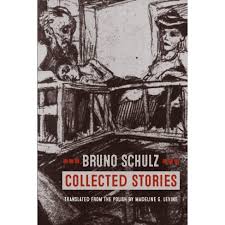

In 1973, a 22-year-old named Jonathan Richman wrote a letter to the editor of Creem. The Detroit magazine, which started in 1969 when both New Journalism and the archetype of the music critic were solidifying in the consciousness of American counterculture, was an iconic purveyor of rock ‘n’ roll criticism and culture. It had recently run a short, positive notice about Richman’s band, the Modern Lovers, whose fast, angry guitar music had given them a reputation in their native Boston. With its signature hopscotch of irony and humor, Creem synthesized the Lovers’ sound: “More than a little like a teenage Velvet Underground.” The magazine called one of their songs, “a guaranteed hit single” and another, “possibly the next national anthem.” Creem’s kidding aside, by most metrics, the Modern Lovers were in a good place in 1973. John Cale, legendary member of the Velvet Underground, was producing the Lovers’ debut album for Warner Brothers when their singer decided to write a letter to Creem. Lovers of a spare prose style, not to mention tight plotting, may be disappointed by Bruno Schulz:

Lovers of a spare prose style, not to mention tight plotting, may be disappointed by Bruno Schulz: To read a novel by D. H. Lawrence is to acquire – not always without resistance – a language of the feelings that is new to us: words we thought we knew well already are made to work in unexpected ways, locating places in the human heart we didn’t know existed, even changing what we understand by human nature. What else, we now ask, were those words ever for? To read Henry James is to inhabit an unaccustomed grammar of thought. Some readers find James’s style tortuous; but those snaking parentheses sharpen our wits; without them we will not keep up with the moral quandaries and vacillations of his characters. They are markers, not just of our penetration, but of our emotional largesse. We are inclined to believe it’s the characters in a novel that extend our sympathies. “We are all of us born in moral stupidity”, George Eliot tells us, whereupon, chastened, we practise acts of reflective empathy on Mr Casaubon. But it is truer to say that it is first of all a novel’s language – its syntactical orchestration of our thinking and feeling faculties – that enables us to go where George Eliot wants us to go, to conceive another person’s equivalence of self with what she rather wonderfully calls “that distinctness which is no longer reflection but feeling”.

To read a novel by D. H. Lawrence is to acquire – not always without resistance – a language of the feelings that is new to us: words we thought we knew well already are made to work in unexpected ways, locating places in the human heart we didn’t know existed, even changing what we understand by human nature. What else, we now ask, were those words ever for? To read Henry James is to inhabit an unaccustomed grammar of thought. Some readers find James’s style tortuous; but those snaking parentheses sharpen our wits; without them we will not keep up with the moral quandaries and vacillations of his characters. They are markers, not just of our penetration, but of our emotional largesse. We are inclined to believe it’s the characters in a novel that extend our sympathies. “We are all of us born in moral stupidity”, George Eliot tells us, whereupon, chastened, we practise acts of reflective empathy on Mr Casaubon. But it is truer to say that it is first of all a novel’s language – its syntactical orchestration of our thinking and feeling faculties – that enables us to go where George Eliot wants us to go, to conceive another person’s equivalence of self with what she rather wonderfully calls “that distinctness which is no longer reflection but feeling”. T

T When Georgia Bowen was born by emergency cesarean on May 18, she took a breath, threw her arms in the air, cried twice, and went into cardiac arrest. The baby had had a heart attack, most likely while she was still in the womb. Her heart was profoundly damaged; a large portion of the muscle was dead, or nearly so, leading to the cardiac arrest. Doctors kept her alive with a cumbersome machine that did the work of her heart and lungs. The physicians moved her from Massachusetts General Hospital, where she was born, to Boston Children’s Hospital and decided to try an experimental procedure that had never before been attempted in a human being following a heart attack. They would take a billion mitochondria — the energy factories found in every cell in the body — from a small plug of Georgia’s healthy abdominalmuscle and infuse them into the injured muscle of her heart. Mitochondria are tiny organelles that fuel the operation of the cell, and they are among the first parts of the cell to die when it is deprived of oxygen-rich blood. Once they are lost, the cell itself dies. But a series of experiments has found that fresh mitochondria can revive flagging cells and enable them to quickly recover.

When Georgia Bowen was born by emergency cesarean on May 18, she took a breath, threw her arms in the air, cried twice, and went into cardiac arrest. The baby had had a heart attack, most likely while she was still in the womb. Her heart was profoundly damaged; a large portion of the muscle was dead, or nearly so, leading to the cardiac arrest. Doctors kept her alive with a cumbersome machine that did the work of her heart and lungs. The physicians moved her from Massachusetts General Hospital, where she was born, to Boston Children’s Hospital and decided to try an experimental procedure that had never before been attempted in a human being following a heart attack. They would take a billion mitochondria — the energy factories found in every cell in the body — from a small plug of Georgia’s healthy abdominalmuscle and infuse them into the injured muscle of her heart. Mitochondria are tiny organelles that fuel the operation of the cell, and they are among the first parts of the cell to die when it is deprived of oxygen-rich blood. Once they are lost, the cell itself dies. But a series of experiments has found that fresh mitochondria can revive flagging cells and enable them to quickly recover.

It turns out you learn a lot when you write a book. This may seem counterintuitive. Perhaps you think, “Well, that’s dumb. If you write a book about something you should already be an expert on it.”

It turns out you learn a lot when you write a book. This may seem counterintuitive. Perhaps you think, “Well, that’s dumb. If you write a book about something you should already be an expert on it.”  When we were teaching at Stanford in the late 2000s, the terms “techie” and “fuzzy” became cultural touchstones: The “techies” majored in engineering and the sciences, the “fuzzies” in arts and the humanities. Faculty and administrators deplored those words, and students furiously debated them, but the terms — and the split they describe —

When we were teaching at Stanford in the late 2000s, the terms “techie” and “fuzzy” became cultural touchstones: The “techies” majored in engineering and the sciences, the “fuzzies” in arts and the humanities. Faculty and administrators deplored those words, and students furiously debated them, but the terms — and the split they describe —  For scientists, pain has long presented an intractable problem: it is a physiological process, just like breathing or digestion, and yet it is inherently, stubbornly subjective—only you feel your pain. It is also a notoriously hard experience to convey accurately to others. Virginia Woolf bemoaned the fact that “the merest schoolgirl, when she falls in love, has Shakespeare or Keats to speak her mind for her; but let a sufferer try to describe a pain in his head to a doctor and language at once runs dry.” Elaine Scarry, in the 1985 book “The Body in Pain,” wrote, “Physical pain does not simply resist language but actively destroys it.”

For scientists, pain has long presented an intractable problem: it is a physiological process, just like breathing or digestion, and yet it is inherently, stubbornly subjective—only you feel your pain. It is also a notoriously hard experience to convey accurately to others. Virginia Woolf bemoaned the fact that “the merest schoolgirl, when she falls in love, has Shakespeare or Keats to speak her mind for her; but let a sufferer try to describe a pain in his head to a doctor and language at once runs dry.” Elaine Scarry, in the 1985 book “The Body in Pain,” wrote, “Physical pain does not simply resist language but actively destroys it.” “My ideal is the cocktail-party chat,” [Jim Holt] writes in the preface to his new essay collection, “When Einstein Walked with Gödel,” “getting across a profound idea in a brisk and amusing way to an interested friend by stripping it down to its essence (perhaps with a few swift pencil strokes on a napkin). The goal is to enlighten the newcomer while providing a novel twist that will please the expert. And never to bore.”

“My ideal is the cocktail-party chat,” [Jim Holt] writes in the preface to his new essay collection, “When Einstein Walked with Gödel,” “getting across a profound idea in a brisk and amusing way to an interested friend by stripping it down to its essence (perhaps with a few swift pencil strokes on a napkin). The goal is to enlighten the newcomer while providing a novel twist that will please the expert. And never to bore.”

In 1997, when Dani Rodrik, a Turkish-born professor at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, published his brief book Has Globalization Gone Too Far?, progressive economists widely embraced his arguments that many free trade policies adopted by the US, which reduced tariffs and other protections, also weakened the bargaining power of American workers, destabilized their wages, and encouraged social conflict. “The danger,” Rodrik wrote presciently, “is that the domestic consensus in favor of open markets will ultimately erode to the point where a generalized resurgence of protectionism becomes a serious possibility.” I remember that Robert Kuttner, the coeditor of The American Prospect, was particularly enthusiastic about the book. Almost twenty years later, he again praised Rodrik for his continued devotion to an empirically grounded skepticism of what Rodrik now calls “hyperglobalization.”

In 1997, when Dani Rodrik, a Turkish-born professor at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, published his brief book Has Globalization Gone Too Far?, progressive economists widely embraced his arguments that many free trade policies adopted by the US, which reduced tariffs and other protections, also weakened the bargaining power of American workers, destabilized their wages, and encouraged social conflict. “The danger,” Rodrik wrote presciently, “is that the domestic consensus in favor of open markets will ultimately erode to the point where a generalized resurgence of protectionism becomes a serious possibility.” I remember that Robert Kuttner, the coeditor of The American Prospect, was particularly enthusiastic about the book. Almost twenty years later, he again praised Rodrik for his continued devotion to an empirically grounded skepticism of what Rodrik now calls “hyperglobalization.”